Information

Journal Policies

Alcoholic Psychoses and Suicide Trends in the Former Soviet Republics

Y. E. Razvodovsky

Copyright :© 2018 Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Background: The Slavic countries of the former Soviet Union (fSU) Russia, Belarus and Ukraine retain one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

Aims: The present study aims to estimate whether harmful drinking is able to explain the dramatic fluctuations in suicide mortality in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine from the late Soviet to post-Soviet period.

Method: Trends in suicide rates and alcoholic psychoses incidence rates (a proxy for harmful drinking) from 1980 to 2010 in Russia Belarus and Ukraine were analyzed employing a time series analysis.

Results: The analysis suggests statistically significant cross-correlation between alcoholic psychoses incidence and suicide mortality rates in Russia (r=0.62; SE=0.183), Belarus (r=0.70; SE=0.183) and Ukraine (r=0.49; SE=0.183) at lag zero.

Conclusion: The findings from present study suggest that alcohol can fully explain the fluctuations in the suicide mortality observed in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods.

Alcoholic psychoses, suicide rates, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine,Psychiatry

1. Background

The Slavic countries of the former Soviet Union Russia, Belarus and Ukraine retain one of the highest suicide rates in the world [23]. The reason of high suicide mortality in fSU countries is not fully understood. A number of variables, including socioeconomic factors, religious and biological background should be considered [1,3,4,6]. The developments in suicide mortality in fSU countries have been particularly dramatic in connection with the societal processes of the last decades including the period of reforms known as “perestroika” and the collapse of the Soviet Union [1,23]. The dramatic fluctuations in suicide mortality in fSU over the past decades have been widely discussed in the scientific literature and are still relatively unexplored [1,4,23].

Accumulated evidence suggests that the mixture of high rate of distilled spirits consumption and binge drinking pattern is a major contributor to the suicide mortality burden in fSU countries [5-7]. Aggregate-level studies also reveal an association between population level drinking and suicide rates in Russia and Belarus [8-20]. Furthermore, evidence of the time series association dates back over a century for the Tsarist era and continues through the Soviet and post-Soviet period [21]. However, several studies did not confirm an association between alcohol consumption and suicide rates in the post-Soviet period [1,4].

The present study aims to estimate whether harmful drinking is able to explain the dramatic fluctuations in suicide mortality in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine from the late Soviet to post-Soviet period. More specifically, this study focuses on a comparative analysis of alcoholic psychoses incidence and suicide trends in these countries between 1980 and 2010.

2.Methods

The data on suicide rates (per 100.000 of the population) and data on alcoholic psychoses incidence rates (per 100.000 of the population) were taken from the WHO mortality database. In this study the alcohol psychoses incidence rate was used as a proxy for harmful drinking. We specified the number of persons admitted to hospital for the first time as incidence of alcoholic psychoses: (ICD–10: F 10). Since alcoholic psychosis is a disease in which patients are usually admitted to hospital, first admission figures are good proxy of the real incidence [17].

To examine the relation between trends in alcohol psychoses incidence rates and suicide rates across the study period a time series analysis was performed using the statistical package “Statistica 12. StatSoft.” The dependent variable was the suicide mortality and the independent variable was alcohol psychoses rate. Bivariate correlations between the raw data from two time series can often be spurious due to common sources in the trends and due to autocorrelation[20]. One way to reduce the risk of obtaining a spurious relation between two variables that have common trends is to remove these trends by means of a “differencing” procedure. This is subsequently followed by an inspection of the cross-correlation function in order to estimate the association between the two prewhitened time series [5,21]. We used an unconstrained polynomial distributed lags analysis to estimate the relationship between the time series of alcohol psychoses incidence and suicide mortality rates in this paper.

3. Results

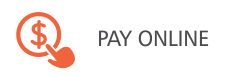

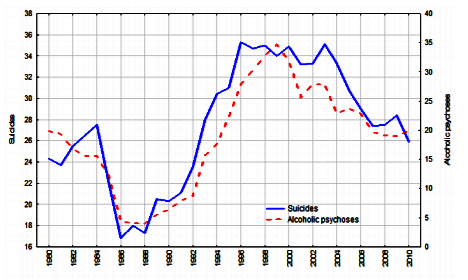

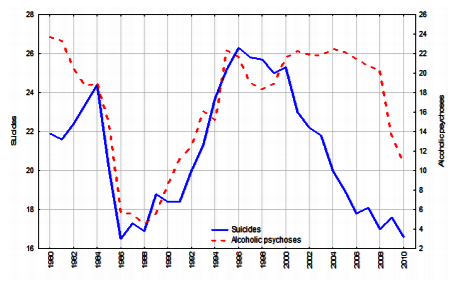

The average suicide rates figure for Russia, Belarus and Ukraine was 29.0±5.9, 27.1±5.9 and 20.8±3.2 per 100.000 respectively. Since the early 1980s, suicide mortality in these countries has undergone sharp fluctuations (Figure 1). In general, the temporal pattern of suicide mortality fluctuations was similar for three countries: sharp decrease in the mid of 1980s, dramatic increase in the first half of 1990s followed by a decline. While the trends in suicide mortality have been similar in three countries during the Soviet period, there was significant discrepancy after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In particular, Russia experienced the sharpest suicide mortality fluctuations during anti-alcohol campaign and transition. In Russia suicide rate jumped dramatically between 1991 and 1994. There was also a spike in suicide mortality between 1999 and 2001 in Russia. In Ukraine and Belarus, suicide rates increased steadily up to 1996 and than started to decrease. The comparative analysis of long-term evolution of suicide rate suggests that in the early 1980s the rate was considerably lower in Ukraine and Belarus than in Russia, but this gap practically disappeared in most recent years.

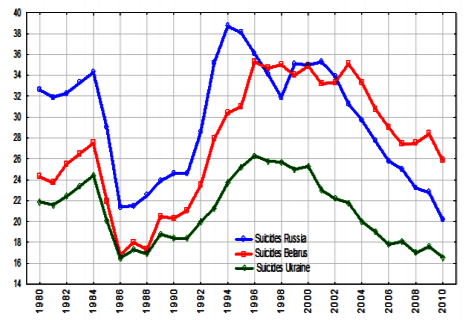

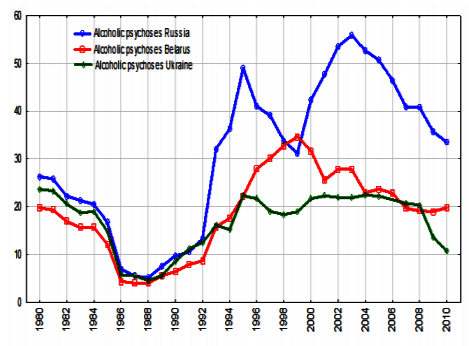

The average alcoholic psychoses incidence rates for Russia, Belarus and Ukraine was 30.8±15.9, 18.7±8.9 and 16.8±6.1 per 100.000 respectively. The trends in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rates are displayed in Figure 2. As can be seen, three countries have experienced similar fluctuations in the alcoholic psychoses incidence rates over the Soviet period. This index decreased markedly from 1980 to 1984, dropped sharply between 1984 and 1988, than started an upward trend from 1998 to 1992. By contrast, there was significant discrepancy in the temporal pattern of alcoholic psychoses incidence rate fluctuations after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Trend in alcoholic psychoses incidence have fluctuated greatly in Russia: jumped dramatically during 1992 to 1995; from 1995 to 1999 there was a fall in the rates before they again jumped between 1999 and 2003, and then started to decrease in the most recent years. In Belarus, alcoholic psychoses incidence increased steadily up to 1999 and then started to decrease. In Ukraine, the incidence of alcoholism increased substantially in the first half of the 1990s reaching its peak in 1995, and then started a downward trend. The graphical evidence suggests that in all countries, the temporal pattern of alcoholic psychoses incidence rate fits closely with the changes in suicide mortality (Figures 3,4,5).

A Spearman’s rank correlation analysis suggests a positive association between alcoholic psychoses incidence and suicide mortality rates in Russia (r=0.43; p< 0,014), Belarus (r=0.92; p< 0.000) and Ukraine (r=0.51; p< 0,004). There were sharp trends in the time series data across the entire study period. These systematic variations were well accounted for by the application of first-order differencing. After prewhitening the cross-correlations between the time series were inspected. The outcome indicates statistically significant cross-correlation between alcoholic psychoses incidence and suicide mortality rates in Russia (r=0.62; SE=0.183), Belarus (r=0.70; SE=0.183) and Ukraine (r=0.49; SE=0.183) at lag zero. The results of the distributed lags analysis also suggest that only contemporaneous correlation (lag 0) is statistically significant in Russia (regress. coeff.=0.25; p< 0.002), Belarus (regress. coeff.=0.49; p< 0.000) and Ukraine (regress. coeff.=0.23; p< 0.016).

4. Discussion

According to the results of present study there was a positive and statistically significant effect of harmful drinking on suicide rates in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine across the study period. The magnitude of this effect was similar in Russia and Belarus and somewhat less evident in Ukraine. These results replicate previous findings that suggested a close link between alcohol and suicide at the aggregate level [7-20].

Some experts have underlined the importance of the effect of the psychosocial distress of economic and political reforms as the main reason for the suicide mortality crisis in the former Soviet republics in the early 1990s [1,4]. The post-Soviet transition has had a dramatic impact on suicide mortality, which is often referred as an indicator of psychosocial distress [1]. In his cross-national analysis Stuckler and coauthors concluded that rapid mass privatization and increased unemployment rate was the major determinant of the mortality crisis in Russia in the early 1990s [22].

There is, however, evidence that an increase in suicide rates during economic crisis is not inevitable. For example, the economic crisis in the former Soviet Baltic republics in 2008 has not been accompanied by an increase in suicide mortality [4]. Furthermore, in an analysis of the determinants of mortality in post-Soviet countries Earle and Gehlbach [2] find no evidence that privatization increased mortality during the early 1990s.

It should be emphasized, that the magnitude of suicide mortality fluctuations during transition was similar in Russia and Belarus, despite the differences in the pace of economic reforms. At the same time, there was significant discrepancy between suicide trends in Russia and Ukraine, despite the similarity in the pace of economic reforms. This evidence suggests that rapid mass privatization, increase unemployment and psychosocial distress do not provide a sufficient explanation for cross-country differences in suicide trends during the transition to the post-communism.

In conclusion, the findings from present study suggest that alcohol can fully explain the fluctuations in the suicide mortality observed in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. The results of present study, as well as findings from other settings indicate that a restrictive alcohol policy can be considered as an effective measure of suicide prevention in countries where rates of both alcohol consumption and suicide are high. Further monitoring of suicide mortality trends in the former Soviet countries and detailed comparisons with earlier developments in other countries remain a priority for future research.

References

- Andreeva E, Ermakov S & Brenner H. The socioeconomic etiology of suicide mortality in Russia. International Journal Environment and Sustainable Development. 2008; 7(1): 21–48.

- Earle JS, Gehlbach S (2010) Mass privatization and the postcommunist mortality crisis, is there a relationship? Upjohn Institute Working Paper No 10: 162.

- Kandrychуn SV, Razvodovsky YE. The spatial regularities of violent mortality in European Russia and Belarus: ethnic and historical perspective. J Psychiatry. 2015. 18: 305 doi: 10.4172/2378-5756.1000305

- Kõlves K, Milner A & Värnik P. Suicide rates and socioeconomic factors in Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union: trends between 1990 and 2008. Sociological Health Illness. 2013; 35(6): 956–70.

- Landberg J. Alcohol and suicide in Eastern Europe. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008; 27: 361–373.

- Mäkinen IH. Eastern European transition and suicide mortality. Social Science & Medicine. 2000; 51: 1405–1420.

- Nemtsov AV. Suicide and alcohol consumption in Russia, 1965-1999. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003; 1: 161–168.

- Pridemore WA. Heavy drinking and suicide in Russia. Social Forces. 2006; 85(1): 413–430.

- Razvodovsky Y.E. Alcohol consumption and suicide rate in Belarus. Psychiatria Danubina. 2006; 18(Suppl.1): 64.

- Razvodovsky YE, Kandrychуn SV. Spatial regularity in suicides and alcohol psychoses in Belarus. Acta Medica Lituanica. 2014; 21(2): 57–64

- Razvodovsky YE. A comparative analysis of dynamic of suicides in Belarus and Russia. Journal of Belarusian Psychiatric Association. 2008; 14: 15-19.

- Razvodovsky YE. Alcohol and suicide in Belarus. Saarbruken: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. 2012.

- Razvodovsky YE. Alcohol and Suicide in Eastern Europe. J Addict Med Ther Sci. 2014; 1(1): 101.

- Razvodovsky YE. Alcohol consumption and suicide rates in Russia. Suicidology Online. 2011; 2: 67–74.

- Razvodovsky YE. Beverage-specific alcohol sale and suicide in Russia. Crisis. 2009b; 30(4): 186–191.

- Razvodovsky YE. Blood alcohol concentration in suicide victims. European Psychiatry. 2010; 25(Supplement 1): 1374.

- Razvodovsky YE. Suicide and alcohol psychoses in Belarus 1970-2005. Crisis. 2007; 28(2): 61-66.

- Razvodovsky YE. Suicide and fatal alcohol poisoning in Russia, 1956-2005. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2009; 16(2): 127–139.

- Razvodovsky YE. Suicide trends in Belarus, 1980-2008. In: Pray, L., Cohen, C., Makinen, I.H., Varnik, A., MacKellar F.L. (Eds.). Suicide in Eastern Europe, the CIS, and the Baltic Countries: Social and Public Health Determinants (pp. 21-28). Viena: Remaprint. 2013.

- Razvodovsky YE. The association between the level of alcohol consumption per capita and suicide rate: results of time-series analysis. Alcoholism. 2001; 2: 35–43.

- Stickley A, Jukkala T & Norstrom T. Alcohol and suicide in Russia, 1870-1894 and 1956-2005: evidence for the continuation of a harmful drinking culture across time? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011; 72: 341–347.

- Stuckler D, King L, McKee M. Mass privatization and post-communist mortality crisis: a cross-national analysis. Lancet. 2009; 373:399-407.

- Värnik A & Wasserman D. Suicides in the former Soviet republics. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1992; 86: 76–78.