Information

Journal Policies

Brief Mentalization-Based Group Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: A Feasibility Study to Assess Safety, Acceptance and Subjective Efficacy

Fernando Lana1,2*,Josep Marti-Bonany1,Gabriel Moreno1,Victor Perez1,2,Maria A.Cruz1

2.IMIM (Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute), Barcelona, Spain.

Copyright :© 2017 Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Background: Bipolar disorder (BD) is a recurrent, difficult to treat condition even with optimal pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Consequently, more effective treatments are needed. Mentalization-based therapy (MBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that may be suitable for BD. Brief mentalization-based group psychotherapy (B-MBGT) is a 12-week program based on the explicit mentalizing techniques of MBT. The present pilot study was conducted to examine the feasibility of B-MBGT to treat patients with BD.

Method: Open study to assess the safety of B-MBGT in 32 patients who met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder. All patients underwent both B-MBGT and Integrated Psychological Therapy (IPT). Consequently, a secondary aim was to compare these two therapies in terms of acceptance and subjective efficacy.

Results: Discomfort during the group treatment session was the most commonly-reported adverse reaction (10 patients, 31.3%); however, the discomfort was considered mild in most cases (8/10; 80%). Compared to IPT, B-MBGT yielded higher scores on seven subjective efficacy parameters, two of which were statistically significant.

Conclusion: B-MBGT is both feasible and safe in BD patients and most patients in this pilot study considered B-MBGT to be beneficial. Controlled studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of B-MBGT.

Bipolar Disorder; Psychosis; Psychotherapy; Group Psychotherapy; Brief Psychotherapy; Mentalization; Mentalizing; Adverse Reaction,Psychiatry

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a highly disabling condition characterized by recurrent episodes of mania/hypomania and depression. Patients with BD may also experience psychotic symptoms, impaired functioning, and poor quality of life[1-4] Suicidal ideation is common in BD, with prevalence rates ranging from 14% to 59%; lifetime rates of completed suicide in this patient group are more than 60 times greater than in the general population[5,6]. BD type I affects around 1% of the world population, but lifetime prevalence rates of the various clinical forms of BD are difficult to estimate because milder forms often remain undiagnosed[2-4,6].

Although mood-stabilizing medication is considered the cornerstone treatment for BD, pharmacological therapy alone is insufficient to fully stabilize the condition in most patients: even among medicated patients, recurrence rates are high, ranging from 40% to 60%[1,7,8].

Importantly, although pharmacological treatments have become somewhat more effective in recent years[3], most patients who experience a mood episode continue to have persistent subthreshold mood symptoms, despite treatment9,10. For this reason, numerous non- medical therapeutic approaches have been recommended to complement medication management in BD[4,5,9-11]. Evidence-based psychotherapy interventions for BD include cognitive-behavioral therapy, family-focused therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, group psychoeducation, mindfulness and systematic care management[2,3,12]. Most clinicians and researchers believe that a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy is the most effective treatment for BD. However, the current evidence suggests that only certain psychosocial interventions targeting specific aspects of BD in selected patient subgroups are useful. Globally, even with optimal pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy recurrences occur in 50–75% of patients at one year[14].

Given this context, it is evident that more effective drugs and psychotherapies are needed to improve outcomes in patients with BD[10]. BD and borderline personality disorder (BPD) share many clinical features, including emotion dysregulation, suicidality, impulsivity, interpersonal difficulties, and treatment non-adherence, among others[14]. Mentalization- based therapy (MBT), an evidence-based, psychodynamically-oriented psychotherapy initially developed to treat BPD, may be applicable to patients with BD to improve emotion regulation, residual mood symptoms, and interpersonal functioning. Several randomized controlled trials (RCT) conducted in patients with BPD have proven the value of MBT to treat a wide range of the clinical features shared by BD and BPD, including suicide attempts, self-injury, hospital admissions, depression, anxiety, general symptom distress, and interpersonal functioning[15,16,17]. In recent years, therapies that include mentalizing as a central component have been developed to treat various disorders, including psychotic disorders[18-20]. MBT is based on research indicating that individuals with significant emotional dysregulation have deficits in their ability to mentalize, which leads to difficulties in managing impulsivity, especially in the context of interpersonal interactions[21,22]. Although MBT techniques have not yet been studied or routinely applied in BD, there are good reasons to believe that they may be helpfu[15,14].

Our group has developed a brief mentalization-based group psychotherapy (B-MBGT) based on our previous experience in developing a psychotherapeutic program to treat patients with severe personality disorders (45% of whom had transient psychotic episodes); in that program, MBT was integrated with other group therapies[23,24]. We also carried out an observational, ambispective study to assess a 12-week B-MBGT program in a sample of patients with severe psychotic disorders (primarily non-affective psychotic patients). The findings from that open study, in which eight (19%) of the patients met DSM-IV criteria for BD type I, yielded preliminary evidence suggesting that B-MBGT might be feasible in individuals with affective psychosis[25].

To our knowledge, no studies have yet been performed to prospectively assess the feasibility of MBT in general, nor B-MBGT in particular, in bipolar patients. Therefore, the purpose of the present pilot feasibility study was to examine the safety, acceptance, and perceived subjective benefits of B-MBGT in a sample of patients diagnosed with BD.

2. Materials And Method

This was a descriptive, prospective, observational study. Patients diagnosed with BD participated in a 12-week B-MBGT program. The primary aims of the study were to assess the safety, acceptance and subjective efficacy of this therapy. Given that all patients underwent both B-MBGT[25,26] and Integrated Psychological Therapy27 (IPT), a secondary aim of this study was to compare these two therapies in terms of patient acceptance and subjective efficacy.

The study was conducted at a day hospital (DH) that forms part of the public mental health network in the metropolitan area of Barcelona (Spain). The study was approved by the local ethics committee (CEIC-Parc de Salut Mar Barcelona), and all patients signed an informed consent form.

The initial study sample (n=35) was selected from all consecutive patients diagnosed with BD and admitted to the DH from April 2014 to November 2017. The DH offers a 4-month treatment plan for these patients. Treatment is delivered from Monday through Friday on an outpatient basis. Patients are admitted to the DH unless they present grossly disorganized behavior, severe suicide risk, daily substance intoxication or withdrawal symptoms, or severe antisocial behavior. In addition to psychopharmacologic treatment, patients admitted to the DH may be offered a range of group therapies, including B-MBGT and IPT. However, patients are excluded from participating in group therapy if they meet any of the following conditions: a) have any previously-scheduled activities (job or vocational rehabilitation, part-time job, etc.) that would interfere with participation; b) fail to attend and tolerate 2-3 weeks of structurally low-demand activities conducted at the beginning of the DH stay (welcoming group, good morning group, health workshop, etc.); c) have insufficient knowledge of the Spanish language Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

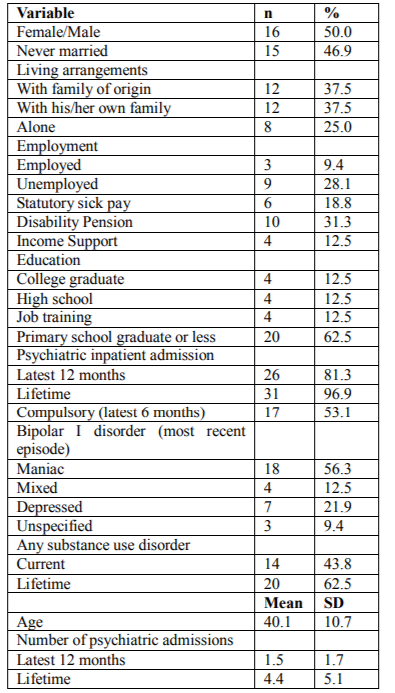

1) mood disorder with psychotic features according to the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview28 (MINI); 2) DSM-IV29 criteria for BD type I, with the most recent episode being one of the following: a) maniac with psychotic symptoms, b) mixed with psychotic symptoms, or c) depressive with psychotic symptoms; and 3) participation in both the B-MBGT and the IPT. Exclusion criteria were: a) severe (> 5) conceptual disorganization and/or b) moderate-severe (> 4) excitement as defined in the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale30. All patients were assessed by a referral therapist by means of a clinical interview in accordance with the DSM-IV criteria. The assessment protocol included the MINI28, a sociodemographic survey (Table 1), a questionnaire on adverse events (Table 2), and a modified questionnaire on perceived intervention benefit31. Of the initial sample of 35 patients, three patients were excluded: in two cases, due to exclusion criteria a, and in one case due to exclusion criteria b. Thus, the final sample included 32 patients. The perceived intervention benefit questionnaire was not available in two cases.

B-MBGT is a group psychotherapy technique based on MBT, a manualized psychodynamic psychotherapy developed by Bateman and Fonagy32 that combines individual and group therapy. Mentalization, a form of social cognition, is a multidimensional construct that is organized around four polarities, one of which involves explicit vs implicit mentalization20. Explicit mentalization is conscious, verbal, and reflective; it requires attention, intention, awareness, and effort. By contrast, implicit or automatic mentalization is nonconscious, nonverbal, and unreflective. The therapy assessed in this study, which has been described in detail elsewhere[25], is based on the explicit mentalizing techniques and the exercises included in the MBT manual[32]. The B-MBGT is a weekly course lasting 50 minutes per session for a maximum of 12 sessions (weeks). The maximum number of patients per group is [10], although at our center the groups are usually smaller (6-8 patients). In the current study, two therapists with extensive psychotherapeutic experience conducted the B-MBGT.

IPT is an effective and evidence-based comprehensive treatment for psychotic patients. For the purposes of this study, we used the “cognitive differentiation” and "verbal communication" subprograms[27,33].

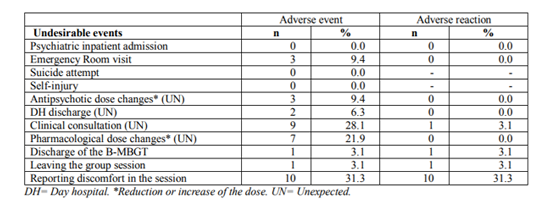

The main outcome variable in the present study was patient safety. Safety was assessed according to the guidelines of the Spanish Agency of Drugs and Health Care Products[34]. A list of potential undesirable events that might occur during the MBGT was drawn up (Table 2). One week after each session all undesirable events experienced by patients (defined as an "adverse event") were recorded on the ad hoc questionnaire. These events were then assessed by the referring therapist and/or the treating psychiatrist to determine whether the event could have been therapy-related (defined as an "adverse reaction"). In addition, the group therapists were questioned to further assess the event. Any discrepancy was resolved by consensus decision. The criteria for differentiating an adverse event from an adverse reaction have been described previously[25]. All adverse events and reactions were attributed to B-MBGT and registered both as dichotomous variables (present or absent) and as count variables (number of events).

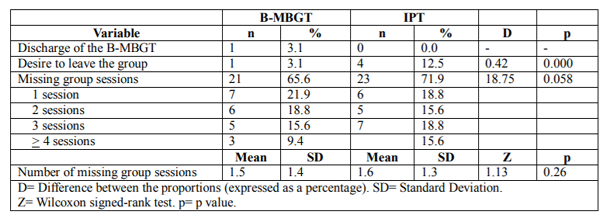

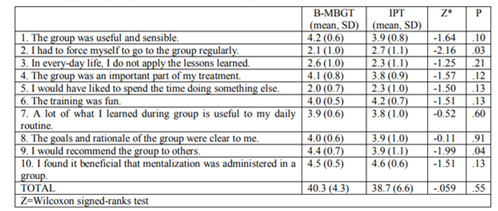

A second outcome variable was acceptance of the B-MBGT, which was evaluated according to the following three factors: 1) number of premature withdrawals from the group, 2) number of patients expressing an explicit desire to withdraw from the group, and 3) frequency and number of absences from the group therapy sessions. Subjective efficacy was evaluated after all group therapy sessions had been completed using a modified questionnaire on perceived intervention benefit developed by Moritz and Woodward[31]. Patient acceptance and subjective efficacy for the two treatments (B-MBGT and IPT) were compared.

The SPSS program (v. 22.0) was used for the statistical analysis. Count and continuous variables were described as means with standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages. All values were calculated, except when expressly indicated, with reference to the total sample. The degree of acceptance between the two groups was compared using McNemar's test for correlated proportions. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare acceptance (as a count variable) and subjective efficacy in BD patients who attended both group therapy modalities. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

The demographic and clinical profile of the total sample is provided in Table 1. Notably, only 9.4% of the patients had been employed in the 6 months prior to admission. Nearly two-thirds (62.5%) of patients had completed compulsory educational level or less. Most patients (81.3%) in the study required psychiatric hospitalization during the previous year and 53.1% of participants required compulsory psychiatric hospitalization in the last 6 months. The average number of lifetime hospitalizations was 4.4 admissions/patient (SD, 5.1; range 0-21). Comorbid substance use disorder was present in 43.8% of patients.

Twenty-one patients (66.6%) experienced an adverse event (Table 2) during the study; however, there was sufficient evidence in only 11 cases (34.4%) to suspect that this event might be therapy-related (i.e., an adverse reaction).

The most common adverse reaction was discomfort during the group session (10 patients, 31.3%), but in most of the cases (8 patients, 80% of patients reporting discomfort) the discomfort was considered only mild.

In terms of therapy acceptance, only one (3.1%) patient dropped out due to B-MBGT and none of the patients who received IPT dropped out. One patient (3.1%) reported a desire to withdraw from the B-MBGT and 4 (12.5%) expressed a desire to leave the IPT group during the “cognitive differentiation” subprogram (notably, all four of these patients had more than a high school education) (Table 3). Two patients (6.3%) left the DH ahead of schedule, but this was unrelated to participation in the B-MBGT or the IPT group. Nearly two-thirds (65.6%) of patients missed at least one B-MBGT session, but in most cases the absence was not B-MBGT-specific but rather because the patient did not come to the DH that particular day; there was only sufficient evidence to suspect that the absence from the session was therapy-related in 2 patients (6.3%). No significant between-group differences (B-MBGT vs IPT) were present in terms of missed sessions.

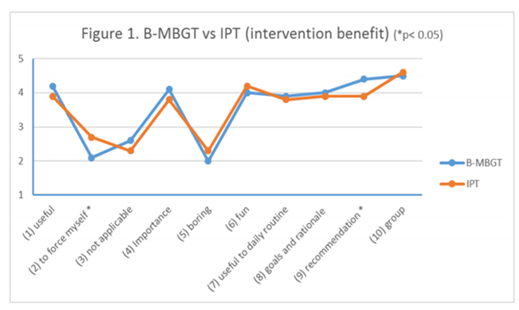

Mean scores on the perceived intervention benefit questionnaire (Table 4) were higher for B-MBGT than CRT on seven subjective efficacy parameters and for the total score;however, only two parameters (resistance and recommend to others) reached statistical significance (Figure 1).

4. Discussion

The main result of the present study is that B-MBGT is safe and well-accepted by patients with BD. Most patients also believed that the therapy was beneficial. Crucially, these results were obtained in a sample of patients with clinically severe BD with psychotic features: nearly all participants (96.9%) had been hospitalized at least once since diagnosis and more than half had required compulsory psychiatric hospitalization in the last 6 months. A large proportion (62.5%) of patients had comorbid substance use disorders and only 9.4% were employed in the last 6 months.

To better understand the potential harmful effects of B-MBGT, we registered all undesirable events (regardless of their potential cause) and attributed all of these adverse events and reactions to B-MBGT, even though it is highly unlikely that all events would be due to this treatment. Nevertheless, even using this very conservative approach, the incidence of undesirable events that might indicate significant clinical worsening (e.g., hospital admission, psychiatric emergency, suicidal behavior and self-injury, and unexpected antipsychotic dose changes) was very low and none of these events were considered adverse reactions (Table 2). Although more than 25% of all patients experienced an undesirable event that suggested a slight change in clinical condition (e.g., unexpected clinical consultation and unexpected changes in prescribed medications), only one of these events was considered an adverse reaction.

The main adverse reaction was discomfort during the group session, which mostly occurred secondary to cognitions or images evoked, or in relation to the theme for a given session. Nevertheless, even when discomfort was reported, in most cases (80%) it was only mild, and patients were able to regulate their emotions without abandoning the group session. The aim of mentalization-based group therapy is to engage patients in a dialogue to foster and maintain mentalizing in the context of stressful interpersonal interactions35. However, it is important that this dialogue be conducted in a more controlled way than in other interpersonal group therapies, mainly due to the type of patient. As Karterud35 points out "groups composed of people with severe psychopathology, when left to themselves with regard to means and ends, tend to alternate between chaos and pseudomentalizing" and, consequently, members of such groups will often be emotionally overwhelmed. For this reason, the group therapist should take control of the group by creating a predictable structure, which is exactly what we do in B-MBGT.

MBGT was well-accepted by the patients. Although a substantial proportion (nearly two-thirds) of participants missed at least one session, in most cases this was because the patient was absent from the DH for the entire day, thus indicating that the absence was not MBGT-specific. The two most common reasons for missing a session were 1) the need to process social benefits and 2) clinical instability. The policy at our center during the first 2-3 weeks of admission to the DH is not to exclude patients from attending the center, even those with clinical instability that could negatively impact their ability to attend the DH every day and/or to arrive on time. As a consequence of this policy, it is not unusual—especially during the first few weeks—for some patients to be absent from the DH at least once per week; as expected, this absenteeism seems to be more common in patients with affective psychosis25.

In terms of subjective efficacy, participants in this study perceived B-MBGT to be at least as helpful as group IPT. Importantly, although IPT is an evidence-based comprehensive treatment originally developed for schizophrenia patients, the creators of that therapy27 recognize that "some of the exercises may be appropriate for nonschizophrenia patients as well". In our experience with postacute psychotic patients admitted to the DH, we have found that IPT is equally beneficial in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders as in those with bipolar spectrum disorders. The only exception to this would be in the cognitive differentiation subprogram among the few patients who have better neurocognitive functioning. Despite the positive patient perceptions of B-MBGT, subjective measures such as this can by no means be considered a proxy for the results of a RCT. All the same, the promising findings of the present feasibility study suggest that further research into the B-MBGT approach for BD is warranted.

Given that a substantial proportion (40-60%) of patients with BD suffer recurrences3 or show only partial or no symptom improvement—even with optimal pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy—new treatment strategies are needed[14]. However, two key aspects should be considered in developing any new treatment approaches: 1) both the neurobiological and psychosocial mechanisms underlying BD[2,3]need to be accounted for, and 2) to assure the economic viability of the intervention, the psychotherapy program should be brief and efficient in order to improve scalability for widespread implementation[36].

B-MBGT is a brief therapy based on mentalizing, which is a form of social cognition that allows us to perceive and to interpret— implicitly as well as explicitly—human behavior as meaningful on the basis of intentional mental states. MBT is based on research indicating that individuals with significant emotional dysregulation have deficits in their ability to mentalize. In this framework, significant stress leads to increased emotional arousal, which interferes with the patient’s ability to make sense of interpersonal events and causes temporary losses in mentalization (i.e., a loss of perspective in interpreting one’s own or others’ motivations). This process results in an increase in self-defeating thoughts, depression or irritability, social withdrawal and may lead to self-harm in some cases[5].

A growing body of research suggests that patients with BD present impaired social cognitive processing37,38,39. Alterations in social cognitive functioning in BD are likely related to changes in patterns of neuronal activation during performance of social cognitive tasks38. Deficits in social cognition (e.g., theory of mind) represent an important predictor of social competence that may impact disease outcome[37,38,40].

The main strength of the present study is that the data were collected as part of usual health care processes and very few patients were excluded, thus reinforcing the external validity of the study. The main limitation is related to the day hospital setting, in which patients receive several different therapies. Moreover, we cannot fully guarantee that the low rate of adverse reactions (i.e., the safety) associated with B-MBGT would be the same in an outpatient setting which lacks the structured, safe environment provided by the DH. Therefore, although the incidence of adverse reactions with B-MBGT was low in the present setting, it would be advisable to take certain precautions13 before administering this therapy in an outpatient setting; the most important precaution would be to require that all patients are clinically stable (i.e., no changes in treatment during the prior 8-12 weeks, except for benzodiazepines or dose reductions related to the positive clinical course) prior to enrolment.

5. Conclusion

BD is a recurrent and disabling condition even when optimal pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is applied. For this reason, there is an urgent need to find more effective medical and psychological therapies. MBT, a psychotherapy initially developed to treat BPD, may be applicable to patients with BD to improve emotion regulation, residual mood symptoms, and interpersonal functioning. Brief mentalization-based group psychotherapy is a short program (12-weeks) grounded on the explicit mentalizing techniques of MBT. The main finding of the present study is that B-MBGT is feasible, safe, and well-accepted by patients with BD. Importantly, most patients also believed that the therapy was beneficial. Controlled studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of this therapeutic approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Bradley Londres for his invaluable assistance in editing the manuscript.

Statement Of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Peña García I, Martín Gómez C, Santamaría C, Sánchez Cubas S, San Pedro L, Lana Moliner F. [Psychosocial treatment of bipolar disorder]. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines. 1998; 26(2):117-128.

- Grupo de Trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Trastorno Bipolar. Guía de Práctica Clínica Sobre Trastorno Bipolar. Madrid; 2012.

- Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013; 381(9878):1672-1682. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60857-0.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Bipolar Disorder: Assessment and Management; 2014.

- Miklowitz DJ. Bipolar Disorder_ Integrating Pharmacology and Psychotherapy 2014. In: Miklowitz DJ& MJG, ed. Clinician’s Guide to Bipolar Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press; 2014:247-268.

- Marwaha S, Sal N, Bebbington P. Bipolar disorder. In: McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R BT, ed. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. Leeds: NHS Digital.; 2016:1-18.

- Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of Recurrence in Bipolar Disorder: Primary Outcomes From the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006; 163(2):217-224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2. 217.

- Van Dijk S, Jeffrey J, Katz MR. A randomized, controlled, pilot study of dialectical behavior therapy skills in a psychoeducational group for individuals with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.054.

- Vieta E, Colom F. Psychological interventions in bipolar disorder: From wishful thinking to an evidence-based approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004; 110(s422):34-38. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00411.x.

- Eisner L, Eddie D, Harley R, Jacobo M, Nierenberg AA, Deckersbach T. Dialectical Behavior Therapy Group Skills Training for Bipolar Disorder. Behav Ther. 2017; 48(4):557-566. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2016.12.006.

- Vallarino M, Henry C, Etain B, et al. An evidence map of psychosocial interventions for the earliest stages of bipolar disorder. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015; 2(6):548-563. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00156-X.

- Miziou S, Tsitsipa E, Moysidou S, et al. Psychosocial treatment and interventions for bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2015; 14(19):1-11. doi:10.1186/s12991-015-0057-z.

- González-Isasi A, Echeburúa E, Mosquera F, Ibáñez B, Aizpuru F, González-Pinto A. Long-term efficacy of a psychological intervention program for patients with refractory bipolar disorder: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2010; 176(2-3):161-165. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.047.

- Miklowitz DJ. Adjunctive Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: State of the Evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165(11):1408-1419. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08040488.

- Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. In: Lieb K, ed. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012:CD005652. doi:10.1002/14651858. CD005652.pub2.

- Lana F, Fernández-San Martín MI. To what extent are specific psychotherapies for borderline personality disorders efficacious? A systematic review of published randomised controlled trials. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2013; 41(4):242-252.

- Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD, Palomba D, Barbui C, Cuijpers P. Efficacy of Psychotherapies for Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2017; 74(4):319-328. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.4287.

- Debbané M, Benmiloud J, Salaminios G, et al. Mentalization-Based Treatment in Clinical High-Risk for Psychosis: A Rationale and Clinical Illustration. J Contemp Psychother. 2016; 46(4):217-225. doi:10.1007/s10879-016-9337-4.

- Weijers J, ten Kate C, Eurelings-Bontekoe E, et al. Mentalization-based treatment for psychotic disorder: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2016; 16(1):191. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-0902-x.

- Bateman A FP. Mentalization-Based Treatment for Personality Disorders. A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Fonagy P, Luyten P. A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2009; 21(4):1355-81. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990198.

- Luyten P, Fonagy P. The neurobiology of mentalizing. Personal Disord Theory, Res Treat. 2015; 6(4):366-379. doi:10.1037/per0000117.

- Lana F, Sánchez-Gil C, Ferrer L, et al. Effectiveness of an integrated treatment for severe personality disorders. A 36-month pragmatic follow-up. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2015; 8(1):3-10. doi:10.1016/j.rpsm.2014.09.002.

- Lana F, Sanchez-Gil C, Adroher N, et al. Comparison of treatment outcomes in severe personality disorder patients with or without substance use disorders: a 36-month prospective pragmatic follow-up study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016; 12:1477-1488. doi:10.2147/NDT.S106270.

- Lana F, Marcos S, Mollà L, Vilar A P V. Mentalization Based Group Psychotherapy for Psychosis: A Pilot Study to Assess Safety, Acceptance and Subjective Efficacy. Int J Psychol Psychoanal. 2015; 1:2:2-6. DOI10.23937/2572-4037.1510007

- Lana F, Cruz MA, Pérez V, Martí-Bonany J. Social Cognition Based Therapies for People with Schizophrenia: Focus on Metacognitive and Mentalization Approaches. In: Schizophrenia Treatment. Dover, DE: SM Group Open Access eBooks; 2017:1-15.

- oder , Mueller DR, Brenner HD, Spaulding WD. Integrated Psychological Therapy IPT for the Treatment of Neurocognition, Social Cognition, and Social Competency in Schizophrenia Patients. Boston: Hogrefe Publishing; 2010.

- Sheehan D V, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R DG. Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998; 59(Suppl 20):22-33.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Ed.). Washington, DC: APA.; 1994.

- Overall J, Gorham D. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. 1962; 10(6):799-812.

- Moritz S, Woodward TS. Metacognitive Training for Schizophrenia Patients (MCT): A Pilot Study on Feasibility, Treatment Adherence, and Subjective Efficacy. Ger J Psychiatry •. 2007; 10:69-78. http://www.gjpsy.uni-goettingen.de.

- Bateman A, Fonagy P. Mentalization-Based Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. doi:10.1093/med/9780198570905.001.0001.

- Roder V, Mueller DR, Mueser KT, Brenner HD. Integrated psychological therapy (IPT) for schizophrenia: is it effective? Schizophr Bull. 2006; 32 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S81-93. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl021.

- Agencia española de medicamentos y productos sanitarios. Información Para Las Notificaciones de Sospechas de Reacciones Adversas a Medicamentos Por Parte de Profesionales Sanitarios. Madrid; 2015.

- Karterud S. Mentalization- Based Group Therapy (MBT-G) A Theoretical, Clinical, and Research Manual. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- ana , anchez-Gil C, Perez , Mart -Bonany J. A stepped care approach to psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder. Ann Clin psychiatry. 2016; 28(2):140-141.

- Montag C, Ehrlich A, Neuhaus K, et al. Theory of mind impairments in euthymic bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2010; 123(1-3):264-269. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.017.

- Cusi AM, Nazarov A, Holshausen K, Macqueen GM, McKinnon MC. Systematic review of the neural basis of social cognition in patients with mood disorders. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012; 37(3):154-169. doi:10.1503 /jpn.100179.

- Haag S, Haffner P, Quinlivan E, Brüne M, Stamm T. No differences in visual theory of mind abilities between euthymic bipolar patients and healthy controls. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016; 4(1):20. doi:10.1186/s40345-016-0061-5.

- Bora E, Bartholomeusz C, Pantelis C. Meta-analysis of Theory of Mind (ToM) impairment in bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2016; 46(2):253-264. doi: 10.1017 /S0033291715001 993.