Information

Journal Policies

Alcohol Psychoses and Gender Gap in Suicide Mortality in Russia

Y.E.Razvodovsky

Copyright :© 2017 Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Background: In most countries, suicide rates are significantly higher for men compared to women, despite women engaging more frequently in suicide attempts. Among the European countries, the gender gap in suicide mortality is particularly high in the republics of the former Soviet Union.

Objective: This study aims to test the alcohol-related hypothesis of the suicide-gender paradox in Russia.

Method: Trends in alcohol psychoses rate (as a proxy for harmful drinking) and gender gap in suicide mortality from 1980 to 2015 were analyzed employing a distributed lags analysis in order to asses bivariate relationship between the two time series.

Results: The results of the time series analysis suggest a positive relation between alcohol psychoses and gender gap in suicides at the aggregate level.

Conclusion: Harmful drinking appears to play an important role in the high gender gap in suicide mortality and its dramatic fluctuations in Russia during the last few decades.

alcohol psychoses, suicides, gender gap, Russia, 1980-2015,Psychiatry

In most countries, suicide rates are significantly higher for men compared to women, despite women engaging more frequently in suicide attempts [1]. In the European region, the average male-to-female rate ratio of suicides is 3.5:1 [2]. Among the European countries, the gender gap in suicide mortality is particularly high in the republics of the former Soviet Union [3].In these republics, male suicide rates exceed those for women by a ratio of more than 5 to 1 [4,5]. The extreme gender imbalance in these countries is due to high suicide rates for men and relatively low suicide rates for women [6,7]. The reasons behind such a drastic gender difference in suicide rates in this region are still poorly understood.

Some researchers attribute the suicide-gender paradox in the former Soviet countries to harmful drinking [6,8-14]. In these countries, male are more prone to high rates of binge drinking of distilled spirits, which can contribute to higher suicide rates among them [15-19]. In line with this evidence we assume that combination of high level of alcohol consumption per capita and binge drinking pattern results in a close link between alcohol psychoses incidence rate (as a proxy for harmful drinking) and gender gap in suicide mortality at the aggregate level in Russia. This study aims to test the alcohol-related hypothesis of the gender paradox of suicidal behavior in Russia.

2. Material And Methods

The data on sex-specific suicide mortality rates (per 1000.000 population) and alcohol psychoses incidence rate (per 100.000 population between 1980 and 2015 were taken from the Rosstat’s (Russian State Statistical Committee) annual reports. In this study the alcohol psychoses incidence rate was used as a proxy for harmful drinking.

To examine the relation between trends in alcohol psychoses rate and gender gap in suicide mortality across the study period a time series analysis was performed using the statistical package “Statistica 12. StatSoft.” The dependent variable was the gender gap in suicide mortality and the independent variable was alcohol psychoses rate. Bivariate correlations between the raw data from two time series can often be spurious due to common sources in the trends and due to autocorrelation [20]. One way to reduce the risk of obtaining a spurious relation between two variables that have common trends is to remove these trends by means of a “differencing” procedure.

This is subsequently followed by an inspection of the cross-correlation function in order to estimate the association between the two prewhitened time series. It was Box and Jenkins[2] who first proposed this particular method for undertaking a time series analysis between the time series. We used an unconstrained polynomial distributed lags analysis to estimate the relationship between the time series of alcohol psychoses rate and gender gap in suicide mortality in this paper.

3. Results

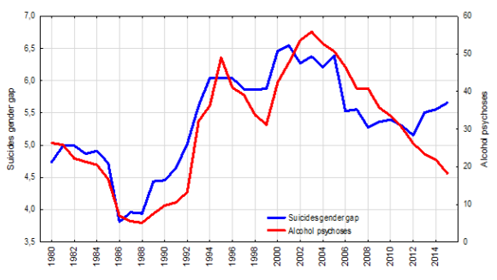

Across the whole period the male suicide mortality rate was 5.4 times higher than the female rate (606.0 vs. 112.4 per 1 000.000) with a rate ratio of 4.7 in 1980 increasing to 5.4 by the 2015. The sharp fluctuations have occurred in the gender gap across the study period (Figure 1). The gender gap in suicide mortality decreased substantially between 1984 and 1986, with the gender gap fell to an all-time low of 3.8, than jumped sharply between 1990 and 1994. From 1995-1998 there was a fall in the gender gap of before it again rose between 1998 and 2001, reaching an all-time high of 6.6, and then started to decrease.

Figure 1 provides graphical evidence that the temporal pattern of gender gap in suicide mortality fits closely with changes in alcohol psychoses rate. A Spearman rank correlation analysis suggests a strong association between the gender gap in suicide mortality and alcohol psychoses rate (r=0.86; p< 0,000). There was a strong trend in the time series across the study period. This trend was removed by means of a first order differencing procedure. After pre-whitening the cross-correlations between alcohol psychoses and gender gap in suicide mortality time series were inspected. The outcome indicated statistically significant cross-correlation between the two variables (r=0.54; SE=0.14). The results of the distributed lags analysis suggest that only contemporaneous correlation (lag 0) is statistically significant (r=0.021;p=0.000).

4. Discussion

The dramatic variations in the gender gap in suicide mortality rates throughout the past decades in Russia suggest that the determinants cannot be purely biological, but might also reflect changes in sex-specific, modifiable risk factors. It is well documented that binge drinking account for extremely higher rate in male suicide mortality in Russia [7-9]. The estimates based on population data suggest that alcohol may be responsible for 61% of male suicides and 35% of female suicides in Russia [11]. The results of the time series analysis, which suggest positive relation between alcohol psychoses and gender gap in suicide rates at the aggregate level indirectly supports the alcohol-related hypothesis.

It seems plausible that the gender gap in suicide mortality was affected by the restriction of alcohol availability during the anti-alcohol campaign in the 1985-1988. Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign did produce a number of positive effects, such as a decline in alcohol consumption, a drop in alcohol-related mortality [16,17]. Similarly, the reduction in the gender gap in suicide rates during the last decade might be attributed to the implementation of the alcohol policy reforms in 2006, which increased government control over the alcohol market [19]. By contrast, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the ending of the state’s alcohol monopoly in the early 1990s were associated with a sharp rise in the gender gap [11]. These facts may be used as empirical evidence suggesting that alcohol is responsible for the gender paradox of suicidal behavior in Russia.

Before concluding, some potential limitations of this study must be acknowledged. It is likely that other factors also contribute to the gender paradox of suicidal behavior in Russia. A possible candidate in this context is psychosocial distress experienced by Russians during the post-Soviet transition [21]. It was hypothesized, that psychosocial distress may be an important factor behind the widening gender gap in suicide rates during the transition period [22]. However, the fact that the upward trend in BAC-positive suicides in the early-1990s was greater than trend in BAC-negative suicides strongly supports an alcohol-related hypothesis [11,23].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, harmful drinking appears to play an important role in the high gender gap in suicide mortality and its dramatic variations in Russia during the last few decades. Further research is needed to clarify more specifically the role of harmful drinking in the gender paradox of suicidal behavior in Russia.

References

- Hawton K. Sex and suicide. Gender differences in suicidal behavior. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000. Vol.177. P. 484–485

- Murphy GE. Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1998. Vol. 39. P. 165–175

- Möller-Leimkühler A. The gender gap in suicide and premature death or: why are men so vulnerable? European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience. 2003. Vol. 253. P. 1-8.

- Varnik A, Wasserman D, Dankowicz M, Eklund G. Age-specific suicide rates in the Slavic and Baltic regions of the former USSR during perestroika, in comparison with 22 European countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998. Vol. 34. P. 20–25.

- Razvodovsky Y.E. Alcohol consumption and suicide rate in Belarus. // Psychiatry Danub. 2006. Vol. 18 (Suppl 1). P. 64.

- Pridemore WA. Heavy drinking and suicide in Russia. Social Forces. 2006. Vol. 85. P. 413– 430.

- Razvodovsky YE. The effects of alcohol on suicide rate in Russia. J Socialomics. 2014. Vol. 3, No.2. P. 1 –6.

- Razvodovsky YE. Alcohol consumption and suicide rates in Russia. Suicidology Online. 2011. Vol. 2. P. 67–74.

- Razvodovsky Y.E. Suicide and fatal alcohol poisoning in Russia, 1956-2005. // Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy. 2009. Vol.16, No.2. P. 127–139.

- Razvodovsky Y.E. Aggregate level effect of binge drinking on suicide mortality rate in Russia. // European Psychiatry. 2014. Vol. 29(Supplement 1). P. 1.

- Razvodovsky YE. Contribution of alcohol in suicide mortality in Eastern Europe. In: Kumar, U. (Ed.). Suicidal behavior: underlying dynamics. New York. Routledge. 2015.

- Stickley A, Jukkala T, Norstrom T. Alcohol and suicide in Russia, 1870-1894 and 1956-2005: evidence for the continuation of a harmful drinking culture across time? J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011. Vol.72. P.341–347.

- Razvodovsky YE. Beverage-specific alcohol sale and suicide in Russia. Crisis. 2009. Vol.30. P. 186–191.

- Razvodovsky Y.E. Alcohol consumption and suicide in Belarus. // Suicidology Online. 2011. Vol.2. P. 1–7.

- Razvodovsky YE. Estimation of the level of alcohol consumption in Russia. ICAP Periodic Review Drinking and Culture. 2013. Vol.8. P. 6–10.

- Moskalewicz J, Razvodovsky Y, Wieczorek P. East-West disparities in alcohol-related harm within European Union. Paper presented at the KBS Annual Conference, Copenhagen, 1-5 June. 2009.

- Nemtsov A.V., Razvodovsky YE. The estimation of the level of alcohol consumption in Russia: a review of the literature. Sobriology. 2017. Vol. 1. P. 78–88.

- Razvodovsky Y.E., Nemtsov A.V. Alcohol-related component of the mortality decline in Russia after 2003. The Questions of Narcology. 2016. Vol.3. P. 63–70.

- Nemtsov AV, Razvodovsky YE. Russian alcohol policy in false mirror. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2016. Vol. 4. P. 21.

- Box GEP, Jenkins GM. Time Series Analysis: forecasting and control. London. Holden-Day Inc. 1976.

- Makinen IH. Eastern European transition and suicide mortality. Social Science & Medicine. 2000. Vol.51. P. 1405 –1420.

- Gavrilova NS, Semyonova VG, Evdokushkina GN, Gavrilov LA The response of violent mortality to economic crisis in Russia. Population Research and Policy Review. 2000. Vol.19. P. 397 –419.

- Razvodovsky YE. Alcohol and suicide in Belarus. Psychiatria Danubina. 2009. Vol. 21(3). P. 290–296.