Information

Journal Policies

A Pilot Evaluation Study of an Intercultural Treatment Program for Stabilization and Arousal Modulation for Intensely Stressed Children and Adolescents and Minor Refugees, Called START (Stress-Traumasymptoms-Arousal-Regulation-Treatment)

Andrea Dixius1*,Adrian Stevens2,Eva Moehler3

Copyright :© 2017 Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Background: During or after periods of intense stress, such as traumatic migration or other experiences children and adolescents are in danger of developing psychiatric or physical symptoms. In these cases frequent barriers to treatment have recenty been described for refugeed minors, including language or cultural impediment. Therefore a short, very low threshold, playful program for emotion regulation and self soothing was developed, the Stress-Traumasymptoms-Arousal-Regulation-Treatment, START.

Methods: Adolescents in acute crisis at the age of 13 – 18 years participated in the START program for 5 weeks in multinational group settings, with two sessions per week. Compounds of START are derived from elements of dialectic behavioral therapy and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children.After informed consent, the first 22 adolescents completing the program twere assessed for trauma (CATS, CPTCI), emotion regulation (FEEL-KJ), general mental and physical Health (RHS), experienced self-control (SCS) and perceived stress (PSS) immediately before and after treatment.

Methods: Traumasepcific symptom load (CATS; CPTCI) was very high in the first 22 adolescents. A positive effect of START on emotion regulation (specifically the scale adaptive stratagies), and self-control can be found as well as a negative effect (reduction) of perceived stress (PSS-10). Also, on a visual analogue scale adolescents scored better for general subjective well being in the refugee health screener after completing the START program.

Conclusion: The results are promising first data supporting the applicability and helpfulness of START in young refugeed minors and other highly stressed adolescents underlining intercutural use with an additional advantage of integration and strengthening of relilience in several at rsik populations. Small sample size is a limitation, as well as the lack of a treatment- as -usual control group. Future studies are warranted.

1. Background

Prevalence of psychiatric disease in unaccompanied refugeed minors is described to be about 80% [1]. In Germany about 60000 unaccompanied refugeed minors were recorded by the Government in 2016 [2]. Varying numbers of psychiatric abnormalities in this population ranging from 20% - 81,5% [3]. Among others, refugeed minors are identified as a highly vulerable risk group, with the lack of psychosocial support increasing the risk for mental health problems in this population [4-7] The short therapeutic program START was developed in clearing contexts for refugeed minors [8,9].

Originally conceived for the work with refugeed minors only, an attraction and potential clinical use for domestic adolescents in stressful situations was discovered [10]. The program consists of very playful elements for self- perception of inner tension. In the second step adolescents try out skills to reduce their tension in an equally playful way, requiring very little speech. The last step is the construction of an indivdual skills box and practising and encouragement to discover own tools for self-regulation, with emphasis on individual strengths and ressources.

The manual contains work sheets in english, arabic, dari/ farsi and german for eachstep/module oft he treatment program as well as colourful illustrations.

START is not designed to work with trauma narratives or exposition -based as this would not be appropriate for adolescents in unstable psychosocial situations.

The basic concept is derived from dialectic behavioral therapy by Marsha Linehan [11]. Skills are tools for improving the mood and reducing negative emotions and tension.

The ability to regulate ones own mood in a succesful way contributes to higher self-effectivenes, a central element for identity development in adolescents [12]. Emotion regulation strategies as well as a sense of self-worth are fundamental elements of resilience [13,14]. In the face of potential future adversity for refugeed minors, it seemed mandatory to enhance emotional resilence.

START therefore integrates elements of dialectic behavioral therapy [15-17] and relexation as well es stabilization techniques of traumafocused cognitive behavioral therapy [18].as well as strategies for dealing with nightmares- the most frequent complaint of adolescents in our clearing and clinic contexts based on the manual of Thünker and Pietrowsky [19].

In the clearing context START was developed and frequently modulated and adapted according to the varying needs of the participants and therefore performed less systematically due tot he varying population of the center. For a systematic evaluation of a highly standardized setting however we introduced START in the clinical setting of a child psychiatric hospital.

2. Methods

A total of 22 patients participated in the five-week follow-up START study of the child and youth psychiatric clinic. The sample consisted of 6 male (27.3%) and 16 female (72.7%) patients aged between 13 – 18 years (Mean = 15.77). 2 of them were out-patient, 20 on an in-patient basis.

Three Afghan (13.6 %) and two Syrian refugees (9.1%), as well as 17 (77.3%) patients from Germany, were included. The majority of the diagnoses consisted of a complex combination of a response to severe stress and adaptation disorder (F43.-) or post-traumatic stress disorder (F43.1) with depressive episodes (F.32.-) or a borderline disorder (F60.31). The inclusion criteria are therefore to be regarded as low-threshold. Criteria for exclusion were psychoses and acute suicidal behavior. Since all participants were able to go through the therapy and diagnostics, no drop-outs were recorded.Adolescents participated twice a week for 5 weeks in 90 min each session. Two therapists in training conducted the group after having received a three hour schooling. The program has been described in more detail in the START-manual and articles oft the authors Dixius and Möhler [8, 10]

. Inclusion Criteria were

. age between 13 and 18

. crisis admission or out patient emergency presentation in child and adolescent psychiatry for self- harm, aggression or suicidal behavior,

. voluntary participation

. Exclusion Criteria

. diagnosis of schizophrenia,

. acute intoxication

This Inventory assesses posttraumatic cognitions on a 25-item scale Clinical relevance is given at a score above 49, [21] Internal consistency oft the scale was Cronbachs Alpha: .86 - .93 and Retest-Reliability: .72 - .78.

Assessment of impulsiveness with 15 items, the total score is constructed by thress subscales: motor impulsivity, non-planned impulsiveness and attention based impulsiveness. We implemented the german version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale - Kurzversion (BIS-15) [22]. Internal consisteny of this scale was good (cronbach alpha: = .81, also convergent validity has been shown by Spinella [23].

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) [24] assesses in10 Items the stress and tension perceived during the last month. PSS is „a measure of the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful. Items were designed to tap how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives. The scale also includes a number of direct queries about current levels of experienced stress“[24]. PSS scales show a consistency of Cronbachs alpha: .84 - .86; retest reliability: .85.[25].

General mental and physical health was assessed by the refugee Health screener [26].

The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) was empirically developed to be a valid, efficient and effective screener for common mental disorders in refugees: Post hoc analyses of the developed RHS-15 showed good sensitivity (range .81 to .95) and specificity (range .86 to .89) to DP's in two of three ethnic groups.

The self-control scale records the own self-control capacity by means of a five-fold step into the scale over 13 items. High values indicate strongly felt self-control and low values correspondending to lower self-control.SCS was hihgly reliable: Cronbachs Alpha: .83 -.85 and retest-reliability: .87 [27]. The german version has been published by Bertrams and Dickhäuser, 2009. On a 5point Likerst Scale this Questionnaire assesses a total score of perceived self-control [28].

The Questionnaire quantifies 15 strategies for emotion regulation of emotions: anxiety, sadness, and anger. This instruments identifies 7 adaptive and 5 maladaptive emotion regulation strategies.Internal Consistency of the 15 scales ranges between α = .69 and α = .91. Secondary scales show a consistency of α = .93 (adaptive strategies) und α = .82 (maladaptive strategies). Retest-Reliability (6-weeks-stability) ranges between rtt = .62 and rtt = .81 and for the secondary scales between rtt = .81 (adaptive strategies) und rtt= .73 (maladaptive strategies) [31].

3. Data Analysis And Statistics

All of the analyses were performed with IBM Statistics SPSS, version 21.0. Wilcoxon Rank test was applied for comparison of pre – versus posttreatment raw scores.

The mean value comparison of the Feel-KJ was performed on the basis of normalized T-values, taking into account the prerequisites by means of a T-test for dependent samples.

4. Results

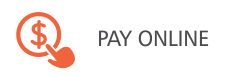

Posttraumatic stress disorder is indicated above a cut-off of 21, The results are presented in (see figure. 1). The PTSD symptoms range in our sample from 10 to 49 with a mean of 34.09 (SD= 12.54. 18 Patients (81.82) of the sample scored above the cut off of 21, as shown by figure 1.

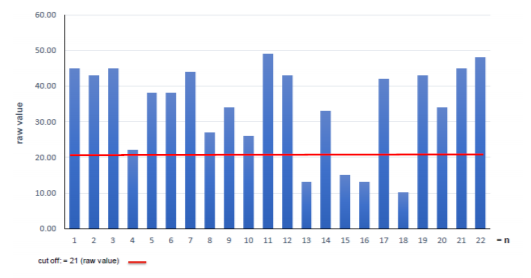

Our sample had results ranging from 34 to 95 with a mean of 68.36 (SD= 16.93). Based on the cut off between 46 and 48 19 Patientes (83.36%) scored above the threshold of posttraumatic stress disorder. On average, 82.5. % of the participants scored positive for clinically relevant PTSD as shown by figure 2

The authors determine a Cut-off of 12 for clinically relevant mental health problems. Based on this cut-off, all 22 probands showed mental health problems, as expected Post intervention 20 cases still scored positive for mental health problems on the RHS However, regarding the ‚symptom load thermometer‘ (Cut-Off >5) 20 cases (90.91%) scored in the range of severe mental problem load before the START-Intervention. After the intervention only 16 cases scored in this range (72.73%).

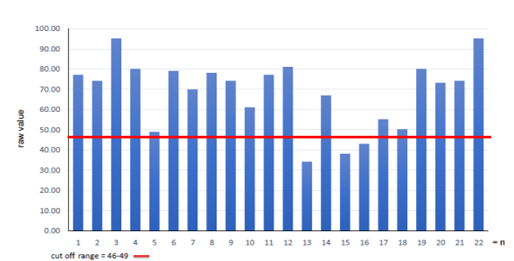

The total raw scare of mental problem load was reduced from 36.2 (Median = 36.00 SD = 10.98) to 31.91 (Median = 36.00 SD = 13.67), thereby showing no significant change. Howefer the reduction of problem load on the thermometer we could show a significant reduction from a mean of 7.07 (Median = 7.00 SD = 1.97) to a mean of 5.67 (Median = 6.00 SD = 2.48) (Asymptotischer Wilcoxon-Test: z = -2.34, p < .05, n = 22). as presented in figure 3.

Die PSS-10 defines a score of 12-14 for normal stress. All 22 patients scored above this with a mean of 35.76 (Median = 37.00 SD = 7.65). However general stress was reduced after the intervention to a mean of 32.05 (Median = 32.00 SD = 11.74), missing significance , with p = .14 a positive trend can be descibed, however.

A significant improvement was found after the intervention in the self-control scale with a mean of 2.71 (Median = 2.54 SD = 0.93) before and a mean of 2.92 (Median =2.76 SD = 0.98) after the intervention. (Asymptotic Wilcoxon-Test: z = 1.76, p = .040, n = 22).

Non-planning Impulsivenes showed a mean of 13.10 (Median = 13.50 SD = 3.28) before the intervention, which was reduced to 11.68 (Median = 12.00 SD = 3.46) after the intervention, a positive trend, however not significant (p= 0.75). Also no significant differences were found for the other 2 scales.

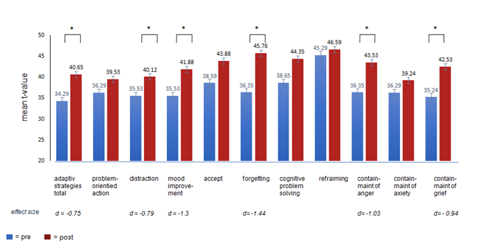

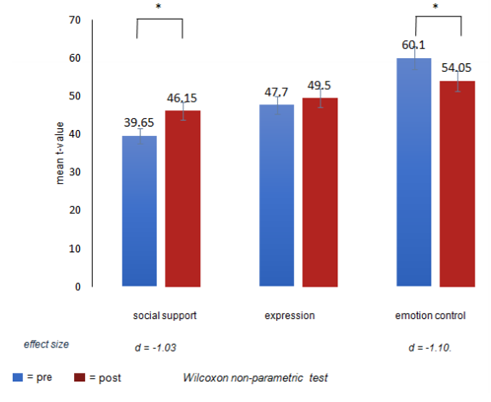

A significant improvement for adaptive strategies from a total 35.95 (SD = 10.40) to 41.93 (SD = 11.05) was found (t = -2.29, p = .018, n = 17). The subscales revealed significant improvements for ‚distraction‘ ‚mood improvement‘ and ‚containment of anger and sadness‘ significant improvements (see table 1). All results are presented in figure 1. The results oft he additional scales social support and emotional control - showing significant improvement- are presented in figure 4. In the area of other strategies, a significant emotions, however, there was a reduction improvement was shown on the basis of social within the standard. (See Table 2)

5. Discussion

This pilot evaluation indicates a usefulness and applicability of START for highly stressed children and adolescents in acute crisis of different nationalities. The largest proportion of our sample (80%) showed posttraumatic stress disorder. All 22 adolescents completed the program, showing good adherence and compliance, once started. The results are limited clearly by small sample size and the lack of a treatment as usual control group.

The most prominent results were as expected can be found for emotion regulation and self control- being the primary target of the 5- weeks program. The expected reduction of perceived stress however was not significant neither was This pilot evaluation indicates a usefulness and applicability of START for highly stressed children and adolescents in acute crisis of different nationalities. The largest proportion of our sample (80%) showed posttraumatic stress disorder. All 22 adolescents completed the program, showing good adherence and compliance, once started. The results are limited clearly by small sample size and the lack of a treatment as usual control group.

The most prominent results were as expected can be found for emotion regulation and self control- being the primary target of the 5- weeks program. The expected reduction of perceived stress however was not significant neither was the general mental health improved on a highly significant basis.

Regarding the fact however, that START is a 5 weeks group program in a highly playful and low threshold manner without narrative elements or trauma exposition it might be concluded that for a strong and significant lasting improvement in general mental health a more profound and individualized therapeutic setting could be nessecary. However, more complex and structured approaches such as DBT and TF-CBT require more behavioral stability than adolescents in acute crisis or transition situations can display o rare willing to develop.

In our sample, in 9 cases TF-CBT or DBT was begun AFTER completion of START, as the patients were found to display enough behavioral stability and therapeutic motivation only after achieving fast success with emotion fregulation and self control.

The primary motivation of START was to enable unaccompanied refugeed minors in acute stages of desparation or tension to regulate their emotions in a way that do not imply harm to self or others. This capability seems to be of utmost importance for a succesful integration and for sustaining the strain of separation, loss and a completely unsecure future. The capability to handle extreme stress without additional necessity for hopsitalization, or involuntary constraint, involving potential re-traumatization is regarded as a major advantage of START.

Future studies should investigate a presumed improvement of self-cofidence potentially accompanying the reduction of non-adaptive behavior with subsequent negative labeling by the immediate environment.

More perceived self- control coud be an important attribute of a positve identity development. A more positive self-conception is expected if integration in schools or youth care settings can be mastered without behavioral disintegration.

However, due to the need for standardized settings, this study presents data gathered in a clinical setting. Orignially START was designed to b e applied by professionals within the youth welfare system or even in schools. Future studies should focus these settings and include broader assessment tools.

This article shows that START achieves his primary goal: a fast behavioral and emotional stavbilization for acuteley stressed adolescents with a high load of traumatic experiences.

6. Clinical Relevance

A short and uncomplicated, low threshold program like START appears to become more and more necessary in the light of increasing numbers of behaviorally dysregulated children and adolescents with or without a history of migration. Due to the simple but structured construction of the manual with work sheets for each steps in different languages it can be applied by child care professionals without intense psychotherapeutic background. The need for improvement of resilience in a world of intense stress and stimulation seems mandatory for adolescencts, specifically refugeed minors an potentially be promoted by START as emotion regulation can be regarded as one central aspect of resilience. This study shows that START can significantly contribute to improve emotion regulation amd therefore potentially stress resilience in adolescents. Future studies in different settings, different age groups and with larger sample sizes are underway.

7. Abbreviations

START: Stress-Traumasymptoms-Arousal-Regulation-Treatment; BIS-15: Barrat Impulsiveness Scale – Kurzversion; RHS-15: Refugee Health Screener; CATS: Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen; CPTCI: Child Post-Traumatic Cognitions Inventory; FEEL-KJ: Fragebogen zur Erhebung der Emotionsregulation bei Kindern und Jugendlichen; PSS-10: Perceived Stress Scale; SCS-13: Self-Control-Scale

8. Declarations

The study was performed in accordance with ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendents. All legal guardians gave their informed consent, and children and adolescents provided their informed assent prior to their inclusion in the study.

9. Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the children and adolescents for their participation in the study.

References

- Hodes, M., Jagdev, D., Chandra, N., Cunniff, A. (2008). Risk and resilience for psychological distress amongst unaccompanied asylum seeking adolescents. Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;49(7):723-32. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01912.x.

- BAMF. Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. Abrufbar unter: https://www. bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/ DE/ Downloads/ Infothek/ Statistik/ Asyl/ aktuelle- zahlen- zu-asyl- april- 2016.pdf? __ blob= publication File (2016). Accessed (10.July 2016)

- itt . assenhofer . egert . lener . ilfe edarf und ilfeange ote in der rsorgung von un egleiteten minder hrigenl chtlingen. Eine systematische Übersicht. Kindheit und Entwicklung, 2015; 24, 209–234.

- Huemer, J., Karnick N.S., Voelkl-Kernstock, S., Granditsch, E., Dervic, K., Friedrich M.H. et al. Mental health issues in unccompainied refugee minors. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health; 2009;.3(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-3-13

- Walg, M., in . ro meier . emprano . apfelmeier .. ufig eit psychischer t rungen ei un egleiteten minder hrigen l chtlingen in eutschland. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2017 Jan; 45(1):58-68. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000459.

- Dixius, A. & Moehler, E.. Komplexe Krisenintervention bei einem 16-jährigen schwangeren Mädchen nach unbegleiteter Flucht aus Eritrea. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2017 Jan; 45(1):69-74. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000458. Epub 2016 Sep 19

- Moehler, E., Simons, M., Kölch, M., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Schulte-Markwort, M., Fegert J.. Diagnosen und Behandlung (unbegleiteter) minderjähriger Flüchtlinge. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2015; 43 (6), 381-383

- Dixius, A. & Möhler, E.START – Entwicklung einer Intervention zur Erststabilisierung und Arousal-Modulation für stark belastete minderjährige Flüchtlinge Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiat. 66: 277 – 286 (2017), ISSN: 0032-7034 (print), 2196-8225 (online) Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen 2017

- Sukale, T., Hertel, C. Möhler, E. Joas, J., Müller, M., Banaschewski, T. Schepker, R., Kölch, M.G., Fegert, J.M., Plener, P.L.iagnosti und rsteinsch t ung ei minder hrigen l chtlingen. Nervenarzt 2017•88:3–9, DOI 10.1007/s00115-016-0244-4,online publiziert: 16. November 2016 Springer-Verlag Berlin

- Dixius, A. & Möhler, E.. Ein neues Therapie-Konzept validiert die besonderen Bedürfnisse geflüchteter Kinder und Jugendlicher: START - Stress-Traumasymptoms-Arousal-Regulation-Treatment. Psychotherapie Forum 2017 DOI 10.1007/s00729-017-0095-x.

- Linehan, M. M.. Dialektisch - Behaviorale Therapie der Borderline-Persönlichkei tsstörung. Trainingsmanual. München: CIP-Medien 1996b

- Foelsch, P.A., Schlüter-Müller, S., Odum, A.E., Arena, H.T., Borzutzky, A.E., Schmeck, K. Adolescent Identity Treatment. An Integrativ Approach of Personality Pathology. 2014. Springer International Publishing Switzerland.

- Rutter M. Psychosocial influences: critiques, findings, and research needs.Dev Psychopathol. 2000 Summer; 12(3):375-405. Review. PMID:11014744

- Rutter M, Sroufe LA. Developmental psychopathology: concepts and challenges. Dev Psychopathol. 2000 Summer;12(3):265-96. Review. PMID:11014739

- Linehan, M. M.. DBT Skills Training Manual.Ney York: The Guilford Press 2015

- Rathus, J.H., Miller, A. DBT Skills Manual for Adolescents. New York: The Guiford Press 2015

- Bohus, M., Wolf, M. Interaktives Skillstraining für Borderline-Patienten. Stuttgart, New York: Schattauer 2011

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P. & Deblinger, E. Trauma fokussierte kognitive Verhaltens therapie bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Heidelberg: Springer; 2009

- Thünker, J., Pietrowsky, R. Alpträume. Ein Therapiemanual. Göttingen: Hogrefe 2011

- Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Holt, T., Jensen, T. K., Jungbluth, N., Risch, E., ... & Goldbeck, L. International development and psychometric properties of the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS). Journal of affective disorders, 210, 189-195.

- Meiser‐Stedman, R., Smith, P., Bryant, R., Salmon, K., Yule, W., Dalgleish, T., & Nixon, R. D. (2009). Development and validation of the child post‐traumatic cognitions inventory (CPTCI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 432-440.

- Meule, A., Vögele, C., & Kübler, A Psychometrische Evaluation der deutschen Barratt Impulsiveness Scale - Kurzversion (BIS-15) [Psychometric evaluation of the German Impulsiveness Scale - Short Version (BIS-15). Diagnostica.; 2011; 57, 126-133.

- Spinella, M. Normative data and a short form of the Barrat Impulsiveness, International Journal of Neuroscience. 2007, 117:3, 359-368,DOI: 10.1080/00207450600588881

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1994). Perceived stress scale. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perieved stress. Journal of Helth and Social Behaviour, Dec. 1983.Vol. 24, No.4, 385-396

- Hollifield, M., Verbillis-Kolp, S., Farmer, B., Toolson, E. C., Woldehaimanot, T., Yamazaki, J. & SooHoo, J. (2013). The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15): development and validation of an instrument for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in refugees. General hospital psychiatry, 35(2), 202-209

- Tangney, J., Baumeister, R.F., Boone, A. L. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology,Better Grades,and Interpersonal Success. Journal of Personality. April 2004, 72:2

- Bertrams, A., & Dickhäuser, O. Messung dispositioneller Selbstkontroll-Kapazität: Eine deutsche Adaptation der Kurzform der Self-Control Scale (SCS-KD). Diagnostica. 2009, 55(1), 2-10.

- Grob, A. & Smolenski, C. Fragebogen zur Erhebung der Emotionsregulation bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (FEEL-KJ). 2009, Bern: Verlag Hans Huber.

- Cracco, E., Van Durme, K., & Braet, C. Validation of the FEEL-KJ: An Instrument to measure emotion regulation strategies in children and adolescents. PloS one.2009. 10(9), e0137080.