Information

Journal Policies

Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Disease

Dr. Abdul Malik Bawah1*, Doklah Kwame Anthony2, Dr. Abdallah Iddrisu Yahaya3

2.Catholic University College of Ghana, Co-Founder and President, toadying news .

3.Senior Lecturer, University for Development Studies, UDS, Dept. Of Medicine and Allied Science, Clinician, Tamale Teaching Hospital, Regional Tb, Clinician, Head of Chest Unit, Tamale Teaching Hospital (TTH) Ghana.

Copyright : © 2018 Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are evolving in both rural and urban areas in Ghana; now predominant among poor people living in urban settings like the Tamale Metropolis. The proportion of people in the Tamale Metropolis who have suffered from NCDs is found to be alarming. This has resulted in increasing prevalence in acute and chronic conditions emanating from complications of NCDs illnesses. Major factors include lifestyle changes such as sedentary activities, dietary habits and general reduction in physical activities that stems from industrialization. The scale of the challenge posed by the growing burden of NCDs places a huge demand on the health system of Ghana for which the country must brace its healthcare system so as to stem down the growing prevalence and the associated complications. Rigorous action is needed to reinforce the district primary health-care system that will integrate the care of chronic diseases and management of risk factors, to develop a national surveillance system, and to apply proven cost-effective primary and secondary care services for such diseases within the Ghanaian population. There is the need for a national initiative to establish service sites in urban, peri-urban and rural settings throughout Ghana to provide preventive healthcare services for non-communicable diseases.

1. Introduction

The third stage of Omran’s transition constituted the age of degenerative and man-made diseases. This stage of transition was largely driven by the social income. Omran, argued that, as infectious and parasitic diseases receded, their place would be taken by series of chronic, degenerative diseases associated with ageing populations such as; cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and cancers. These diseases will become significant causes of mortality. More recently, two more stages have been added (the fourth and fifth stage) A countries age structure may convey important information on the most prevalent diseases, as may population racial/ethical distribution. Modifiable risk factors feresb to four major ones for NCDs; poor diet, physical inactivity, tobacco use, harmful alcohol use (WHO 20011). According to Dalals et al, the prevalence of NCDs and their risk factors is high in some SSA settings, with lack of vital statistics systems; epidemiological studies with variety of in-depth analysis of risk factors could provide a better understanding of NCD in the Tamale Metropolitan Assemble of Northern Ghana. With current prevalence reaching epidemic proportions, the World Health Organization (WHO) has predicted that developing countries would bear the brunt of diabetes in the 21st century.

It said available statistics indicates that currently more than 70 per cent of people with diabetes lived in low and middle income countries, with prevalence increasing dramatically in Africa with an estimated 10.4 million people with the condition in 2007.

In Ghana, about four million people may be affected with diabetes mellitus, which is a group of metabolic diseases in which a person has high blood sugar, a condition which could be attributed to situations where either the body does not produce enough insulin or because cells do not respond to the insulin that is produced; but it could be controlled and managed with little injections of insulin. (only 500,000 registered).

Diabetes is said to be one of the risking killer diseases globally, claiming one life every eight seconds and a limb lost at every 30 second, according to reports from WHO and the international Diabetes Federation (IDF).

In a speech read for him, Mr. Alban Kingsford Bagbin, Minister of Health at the opening session of a three-day Training Workshop of Diabetes Nurse Education in Accra on Wednesday, said the Atlas of IDF showed that the number of people with diabetes in Accra would increase by 80 per cent to 1807 million by 2025.

The sector minister noted that currently, Ghana Health Service had a doctor to population ratio of 1 to 11,929 stressing the fact that lack of financial means was not the only challenge, but a scarcity of trained health care personnel capable to tackle the prevention, diagnosis and management of diabetes at all levels of the health care systems.

The workshop was organized by the Ithemba Foundation Ghana (IFG), an NGO in collaboration with the ministry of health for 37 diabetes nurse educators drawn from selected health facilities to improve the quality of diabetes care in the country.

It was aimed at equipping participants with expanded knowledge on the disease to enable them relate quality information and serve as lifelines to people living with the condition at the various diabetes clinics nationwide as well as being ambassadors in their communities.

Mr. Bagbin stressed on the need to design and adopt national diabetes plans that relied on a multi-level system of care, adding the training of physicians, nurses and health care staff was a plus in combating the incidence of diabetes and other non-communicable diseases in Ghana.

He commended the organizers for the initiative and called for the active involvement and support of all stakeholders, adding that with the above highlights, there could be quite a number of sufferers walking on the streets without access to basic information and primary care.

Mr. Samuel Denyoh, Executive Director, IFG, said there were unknown number of people who died from lack of proper management, coupled with ignorance of the disease in Ghana.

"It was clear that if not addressed as a matter of urgency, diabetes, will soon threaten the economic viability of the nation. And sadly, many people who survive HIV and AIDS may die of diabetes," he said.

Mr. Denyoh said the treatment of diabetes was immense and increasing in Ghana, adding "Currently over two million people are known to be living with the condition and the nation will not, and is not escaping the impact of diabetes".

He stressed that undetected, untreated or poorly controlled diabetes could result in devastating long-term complications such as blindness, amputation, kidney diseases, stroke, heart attack, erectile dysfunction and life threatening short-term complications as ketoacidosis and severe hypoglycemia.

The need to avoid the potentially disastrous impact of diabetes in Ghana was paramount, acknowledging that government alone cannot shoulder the responsibility, therefore the initiative by IFG to ensure that people living with diabetes received adequate knowledge about the condition.

"This would however prevent, if not reduce the occurrence of both short-term and long-term complications", he said. Mr. Stephen Coffie, vice president of the National Diabetes Association, appealed to nurses and other health care providers to embrace people living with diabetes with love, passion, care and support; stressing that any form of hostility towards them could trigger complications, creating trauma or leading to untimely deaths.

He said diabetes mellitus was a complex chronic disease and diabetes nurse educators, would be expected to communicate large amounts of complex information to patients with diabetes and help them learn the skills needed to manage their disease on daily basis.

Mr. Coffie gave the assurance that the Association would look for further sponsorship from government and their source for training in foot care and wound management in diabetes patients.

Mr. Ernest Ababio, Director PLAB Pharmaceuticals, urged families to conduct regular diabetes checks to ensure early detection to ensure prevention.

Non-communicable diseases have been established as a clear threat not only to human health, but also to development and economic growth. Claiming 63% of all deaths, these diseases are currently the world’s mainkiller. Eighty percent of these deaths now occur in low and middle income countries (World Economic Forum, 2010). Half of those who die of chronic non-communicable diseases are in the prime of their productive years and thus, the disability imposed and the lives lost are also endangering industry competiveness across borders, Recognizing that building a solid economic argument is ever more crucial in times of financial crises, this report brings to the global debate fundamental evidence which had previously been missing: an account of the overall costs of NCDs including what specific impact NCDs might have on economic growth.

The evidence gathered is compelling. Over the next 20 years, NCDs will cost more than US$ 30 trillion, representing 48% of global GDP in 2010, and pushing millions of people below the poverty line. Mental health conditions alone will account for the loss of an additional US$ 16.1 trillion, over this time span, with dramatic impact on productivity and quality of life.

By contrast, mounting evidence highlights how millions of deaths can be averted and economic losses reduced by billions of dollars if added focus is put on prevention. A recent world health organization report underlines that population based measures for reducing tobacco and harmful alcohol use, as we11 as unhealthy diet and physical inactivity, are estimated to cost USS 2 billion per year tar all low and middle income countries, which in fact translates to less than USS 0.40 per person.

The rise in the prevalence and significance of NCDs is the result of complex interaction between health, economic growth and development, and it is strongly associated with universal trends such as ageing of the global population, rapid unplanned urbanization and the globalization of unhealthy lifestyles. In addition to the tremendous demands that these diseases place on social welfare and health systems, they also cause decreased productivity in the workplace, prolonged disability and diminished resources within families.

The results are unequivocal: a unified front is needed to turn the tide on NCDs. Governments but also civil society and the private sector must commit to the highest level of engagement in combating these diseases and their rising economic burden. Global business leaders are acutely aware of the problems posed by NCDs. A survey of business executives from around the world conducted by the world economic forum since 2009, identified NCDs as one of the leading threats to global economic growth. Therefore, it is also important for the private sector to have a strategic vision on how to fulfil its role as a key agent for change and how to facilitate the adoption of healthier lifestyles not only by consumers, but also by employees.

The need to create a global vision and a common understanding of the action required by all sectors and stakeholders in society has reached top priority on the global agenda this year, with the United Nations General Assembly convening a high level meeting on the prevention and control of NCDs.

If the challenges imposed on countries, communities and individuals by NCDs are to be met effectively this decade, they need to be addressed by a strong multi-stakeholder and cross-sectorial response, meaningful changes and adequate resources. We are pleased and proud to present this report, which we believe will strengthen the economic case for action (Klaus schwab; Julio Frenk: founder and executive chairman World Economic Forum).

As policy makers search for ways to reduce poverty and income inequality, and to achieve sustainable income growth they are being encouraged, to focus on an emerging challenge to health, well-being and development: non- communicable diseases (NCDs).

After, 63% of all deaths worldwide currently stem from NCDs - chiefly cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. These deaths are distributed widely among the wor1d’ population - from high income to low income countries and from young to old (about one quarter of all NCD deaths occur bellow the age of 60, amounting to approximately 9 million deaths per year). NCDs have a large impact, undercutting productivity and boosting healthcare outlays. Moreover, the number of people affected by NCDs is expected to rise substantially in the coming decades, reflecting the ageing increasing global population.

With this in mind, the United Nations held its first high level meeting on NCDs on 19-20 September 2011 – this was only the second time that a high level UN meeting was being dedicated to a health topic (the first time being on HIV/AIDS in 2001). Over the years, much work has been done estimating the human toll of NCDs but work estimating the economic toll is far less advanced.

In the report, the world economic forum and the Harvard school of public health try to inform and stimulate further debate by developing new estimates of the global economic burden of NCDs in 2010, and projecting the size of the burden through 2030. Three district approaches are used to compute the economic burden: (1) the standard cost of illness method; (2) macroeconomic simulation and (3) the value of a statistical life. This report includes not only the four major NCDs (the focus of the UN meeting), but also mental illness, which is a major contributor to the burden of disease worldwide. This evaluation takes place in the context of enormous global health spending, serious concerns about already stained public finances and worries about "lackluster" economic growth. The report also tries to capture the thinking of the business community about the impact of NCDs on their enterprises.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) impose a large burden of human health worldwide. Currently, more than 60% of all deaths worldwide stem from NCDs. Moreover, what were once considered "diseases of affluence" have now encroached on developing countries.

In 2008, roughly four out of five NCD deaths occurred in low and middle income countries (WHO.2011), up sharply from just under 40% in 1990 (Murray and Lupez,1997). Moreover,NCDs are among people bellow the age distribution – already, one-quarter of all NCD-related deaths are among people bellow the age 60 (WHO,2011). NCDs also account for 48% of the healthy life years lost (Disability Adjusted life years – DALYs) 1 worldwide (versus% for communicable disease, maternal and perinatal conditions and nutritional deficiencies and 1 % for injuries) WHO 2005.

Adding urgency to the NCD debate is the likelihood that the number of people affected by NCDs will raise substantially in the coming decades. One reason is the interaction between two major demographic trends. World population is increasing, and although the rate of increase has slowed, UN projections indicate that there will be approximately 2 billion more people by 2050. In addition, the share of those aged 60 and older has begun to increase and is expected to grow very rapidly in the coming years. Since NCDs disproportionately affect this age group, the incidence of these diseases can be expected to accelerate in the future. Increasing prevalence of key risk factors will also contribute to the urgency, particularly as globalization and urbanization take greater hold in the developing world.

NCDs stem from a combination of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors.

Non- modifiable risk factors refer to characteristics that cannot be changed by an individual (or the environment) and include, age, sex and genetic make-up. Although, they cannot be the primary targets of interventions, they remain important factors since they affect and partly determine the effectiveness of many prevention and treatment approaches.

A country’s age structure may convey important information on the most prevalent diseases, as may the population racial/ethnic distribution. Modifiable risk factors refer to characteristics that societies or individuals can change to improve health outcomes. WHO typically refers to four major ones for NCDs: poor diet, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and harmful alcohol use (WHO 2011).

2. Poor Diet and Physical Inactivity

The composition of human diets has changed considerably over time, with globalization and urbanization making processed high in refined starch, sugar, salt, and unhealthy fats cheaply and readily available and enticing to consumers – often more so than natural foods (Hawkes 2006). As a result, over weight and obesity and associated health problems are on the rise in the developing world (Cecchini, et al 2010). Exacerbating matters has been a shift towards sedentary lifestyles, which has accompanied economic growth, the shift from agricultural economies to service based economies and urbanization in the developing world. This spreading of fast food culture, sedentary lifestyles, and increase in body weight has lead for some to coin the emerging threat as "globesity" epidemic (Bifuleo and Caruso, 2007, Dietel, 2002, Schwartz, 2005).

3. Tobacco

High rates of tobacco use are projected to lead to a doubling of the number of tobacco-related deaths between 201O and 2030 in low- and middle-income countries. Unless stronger action is taken now, the 3.4 million tobacco-related deaths today will become 6.8 million in 2030 (NCD Alliance, 2011). A 2004 study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predicted that developing countries would consume 7 1% of the world’s tobacco in 2010 (FAO, 2004). China is a global tobacco hotspot, with more than 320 million smokers and approximately 35% of the world’s tobacco production (FAO, 2004; Global Adult Tobacco Survey – China Section, 2010). Tobacco accounts for 30% of cancers globally, and the annual economic burden of tobacco-related illnesses exceeds total annual health expenditures in low- and middle-income countries (American Cancer Society & World Lung Foundation, 2009).

4. Alcohol

Alcohol use has been causally linked to many cancers and in excessive quantity with many types of cardiovascular disease (Boffetta & Hashibe, 2006; Ronksley, Brien, Turner, Mukamal, &Ghali, 2011). Alcohol accounted for 3.8% of deaths and 4.6% of DALYs in 2004 (GAPA, 201 1). Evidence also shows a causal, close-response relationship between alcohol use and several cancer sites, including the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, liver and female breast (Rehm, et a1. 2010).

The pathway from modifiable risk factors to NCDs often operates through what are known as risk factors"- which include overweight/obesity, elevated blood glucose high blood and high cholesterol. Secondary prevention measures can tackle most of these risk factors as changes in diet or physical activity or the use of medicines to control blood pressure and oral agents or insulin to control blood sugar and pharmacological/surgical means to control obesity.

Although intervening on intermediate risk factors may be more effective (and more cost- effective) have fully developed, treating intermediate risk factors may, in turn, be less effective) than primary prevention measures or creating favorable social reduce vulnerability developing disease (Brownell Frieden, 2009; National Commission on Prevention priorities, 2007; Satcher, 2006; Woolf. 2009).

After all, even those with the will to engage in healthy practices may find it difficult to do so because live or working in environments that restrict ability to make healthy choices. For these reasons, they need to address social determinants of NCDs was reiterated at the 64th World Health Assembly held in Geneva, Switzerland in May 2011 by WHO Member States in preparation for UN High-Level Meeting in September 2011. Macro-level contextual factors include he built and social environment: political economic and legal systems; the policy environment: culture, and education. Social determinants are often influenced by political systems; whose operation leads to important decisions about the resources dedicated to health in a given country. For example, in the United States, free market systems often promote an individualistic cultural and social environment which affects the amount of resources allocated for healthcare how these resources are spent and the balance of state versus out-of-pocket expenditures that are committed to protect against and cope with the impact of disease (Kaiser 20l0; Siddiqi, Zuberi & Nguven 2O09). Political systems that promote strong social safety nets tend to have fewer social inequalities in health (Beckfield & Krieger. 2009; Navarro and Shi, 2001).

Social structure is also inextrica1ly linked with economic wealth, with the poor relying more heavily on social support through non-financial exchanges with neighbors, family and friends to protect against and cope with the impact disease. Wilkinson and Marmot have written extensively on the role that practical, financial and emotional support plays in buoying individua1s in times of crisis, and the positive impact this can have on multiple health outcomes including chronic disease (Wilkinson & Marmot. 2003).

The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) reports that the proportion of the world’s population 1iving in urban areas surpassed half in 2008. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) estimates that by 2050 two-thirds of people around the world wil1 live in urban areas. Approximately 1 billion people live in urban slums. According to the LIN, 6.5% of cities are made up of slums in the developed world while in the developing world the figure is over 78%.

Although most studies note an economic "urban advantage" for those living in cities because of greater access to services and jobs, this advantage is often diminished by the higher cost of living cities and low quality of living conditions in urban slums (ECOSOC, 2010).

In addition, urbanization and globalization heavily influence resource distribution within societies, often exacerbating geographic and socioeconomic inequalities in health (Hope, 1989; Schuftan,1999). Notably, a 100-country study by Ezzati et al. found that both body mass index (BMI) and cholesterol levels were positively associated with a rise in urbanization and national income (Ezzati et al., 2005). At a regional level, a study conducted by Allender et al. Similarly found strong links between the proportion of people living in urban areas and NCD risk factors in the state of Tamil Nadu, India (Allender, et al., 2010).

This study observed a positive association between urban city and smoking, BMI, blood pressure and low physical activity among men. Among women, urban concentration was positively associated with BMI and low physical activity. Similar findings have been observed in other countries as well (Vlahov & Galea, 2002). A growing literature has emerged on the effect of the built environment and global trends toward urbanization on health (Michael, et al., 2009).

Education matters, too. This effect is at least partially attributable to the better health literacy that results from each additional year of formal education. Improved health literacy has been linked to improved outcomes in breastfeeding, reduction in smoking and improved diets and lowered cholesterol levels (ECOSOC, 2010).

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in Ghana accounted for an estimated 39 per cent of all mortality in 2008. In 2008, the most prevalent NCDs were cardiovascular diseases (18 percent).

Cancers, non-communicable variants of respiratory diseases and diabetes contributed 6 per cent, 5 percent and 1 per cent to total mortality respectively (2008).

5. Non-Communicable Diseases In Northern Ghana

The prevalence of major chronic non- communicable diseases and their risk factors has increased over time and contributes significantly to the Ghana’s disease burden. Conditions like hypertension, stroke and diabetes affect young and old, urban and rural, and wealthy and poor communities. The high cost of care drives the poor further into poverty. Lay awareness and knowledge are limited health systems (biomedical, ethno medical and complementary) are weak, and there are no chronic disease policies. These factors contribute to increasing risk, morbidity and mortality. As a result, chronic diseases constitute a public health and a developmental problem that should be of urgent concern not only for the Ministry of Health, but also for the Government of Ghana.

New directions in research, practice and policy are urgently needed. They should be supported by active partnerships between researchers, policymakers, industry, patient groups, civil society, government and development partners.

Major causes of death in Northern Ghana have shifted from predominantly communicable diseases to a combination of communicable and chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) over the last few decades. Hypertension, stroke, diabetes and cancers have become top 10 causes of death. Urbanization, changing lifestyles (including poor diets), ageing population’s globalization and weak health systems are implicated in chronic disease risk, morbidity and mortality.

Despite recognition of a growing chronic disease burden in the early 1 990s, a series of low interventions over the last fifteen years, and a national health policy that emphasizes health and prevention of lifestyle diseases, Ghana does not have a chronic disease policy or a plan. These structural deficiencies compound the financial and psychosocial chal1enge individuals, caregivers and families affected by chronic diseases.

This Ghana Medical Journal Supplement Issue on Ghana’s chronic disease burden the proceedings of the first annual workshop of the UK-Africa Academic Partnership on Chronic Disease held at the Noguchi Memorial institute for Medical Research in April 2007. The workshop aimed to collate interdisciplinary information on Ghana’s chronic disease burden as a starting point for engaging with national policy development and implementation, as well as with broader regional and international trends at subsequent meetings.

The partnership’s flagship special issue published in Globalization and Health addressed local and global perspectives on Africa’s chronic disease burden. This supplement offers insights into four key areas of the Ghana’s NCD burden: epidemiological, clinical, and psychosocial and intervention/ policy. Some papers offer important comprehensive reviews of NCD research conducted over the last 40 years. Brief comments are made on these themes and future directions in research, practice and policy are outlined.

The epidemiological themes focus on hypertension, stroke, and diseases of ageing, asthma and mental illness. Cross-cutting themes suggest that epidemiological studies are limited, prevalence of focal conditions are rising and ‘future research must priorities robust population-based research to improve prevention, detection, treatment and control of common conditions. The clinical themes focus on management of stroke, asthma, type 1 diabetes and cancers. NCD management is generally poor. Poor clinical care and poor self- care - both due partly to limited professional and lay knowledge – are implicated in avoidable complications and premature deaths.

The psychosocial themes illuminate the psychological, social, cultural and economic contexts of living with type 1diabetes, terminal chronic conditions, mental illness and other common NCDs and provide insights into lay ideas and beliefs about common NCDs. There is agreement that policy responses to Ghana’s NCD burden have been inadequate and that greater efforts are needed to bridge the gap between policy rhetoric and action.

Population-based studies, as well as action oriented research - e.g. implementation impact, operational, evaluation studies - should be prioritized. More research is required, for example, on asthma in the adult population, to understand what happens to stroke patients after discharge, the help-seeking behavior across medical systems and to estimate the indirect costs of NCDs on households. Impact studies on the psychosocial benefit of patient support groups are required to incorporate the work of patient and advocacy groups more adequately in medical care.

Robust qualitative and ethnographic studies are needed to increase understanding of the complex psychological and cultural contexts of risk, illness experience, care giving and social attitudes.

Interventions must be multi-pronged and encompass primary and secondary prevention. Improved health communication strategies are needed to improve awareness and behavior change. It is essential that interventions are targeted to young persons, regions with high prevalence (e.g. Greater Accra and Ashanti), and high-risk populations (obese individuals; individuals with multiple risks and co-morbid conditions). Health services need to be strengthened, to improve the capacity of peripheral institutions to deliver quality care and to reduce the congestion in the tertiary level facilities.

Poor knowledge and attitudes of health practitioners on chronic diseases undermine quality of care. It is important to include chronic disease management in the continuous professional development activities of health workers and to develop guidelines valid for local use.

Policy neglect has been due partly to limited research, weak surveillance systems and the lack of reliable data, limited political interest and donor investment. Innovative ways of mobilizing funds and strengthening political will to support NCD control and prevention are required. In Ghana, achievable interventions include passing tobacco legislation and passing or enforcing laws on food labeling to reduce salt and energy content of processed foods. The drive to enroll more registrants to the NHIS should be intensified as well as restructuring benefits package to include more chronic disease medicines and treatment. Best practice models in other African countries - such as South Africa and Cameroon - can inform Ghanaian research, practice and policy.

Chronic NCDs contribute significantly to the nation’s disease burden. They constitute both a public health and a developmental issue that should be of urgent concern not only for the Ministry of Health, but also for the Government of Ghana. Pertinent challenges include limited knowledge of NCDs in the general population which contributes to late reporting to clinics for care, high costs of medicines and high rates of preventable complications. NCDs affect poor communities the catastrophic costs of care drive them deeper into poverty.

The UN convened a High-level Meeting on NCDs in September 2011. Ghana participated in the conference, and endorsed the draft political declaration passed on NCDs. Central themes of the declaration included the adoption of a "whole-of-government and a whole of-Society effort" in tackling national NCD burdens. Ghana has a history of participating and endorsing several international, regional and subre0nal resolutions and declarations on chronic diseases do not get implemented.

To bridge the gulf between policy rhetoric and implementation, joint action by government (and its various relevant sector ministries), health and public policymakers, industry, Civil Society, researcher and patient groups is urgently needed. The government needs to give high priority, to policies and funded programs for the prevention and control of chronic diseases.

Public-private partnerships with the pharmaceutical industry should aim to ensure availability, affordability and accessibility of low-cost generic drugs for the management of chronic diseases. Researchers need to focus efforts on implementation research questions relevant to Ghana.

It has been recognized that as society’s modernism they experience significant changes in their patterns of health and disease. Despite rapid modernization across the globe, there are relatively few detailed case studies of changes in health and disease within specific countries especially for sub-Sahara Africa countries. This paper presents evidence to illustrate the nature and speed of the epidemiological transition in Northern Ghana.

Ghana socio economic and demographic changes and burden of chronic disease. Our review indicates that the epidemiological transition in Accra reflects a protracted polarized model.

A "protracted" double burden ¡s polarized a cross social class. While wealthy communities experience higher risk of chronic disease, poor communities experience higher of infectious diseases and a double burden of infectious and chronic diseases. Urbanization, urban poverty and globalization are key factors in the transition. We explore the structures and processes of these factors and consider the implications for the epidemiological transition in Northern Ghana.

6. Methodology

Tamale is the capital of northern Ghana and has a population of three hundred and seventy one thousand (371,000) people (Ghana Statistical Service, 2010, Census). The population growth has been within a very short period with no plan for urbanization since 1960.

Focus group discussion and individual interview with questionnaires; Research assistance helped to translate from English to Dagbani, Hausa or Twi.

Focal group discussions: a group be made up of 8 to 12 people, with same topics as in qunestionnaire will be discussed. Male group shall be isolated from female group.

Individual interview (questionnaire), 10 questions shall be on each paper. Interview questions shall be directed towards giving idea of knowledge (lay information) of non- communicable disease by the individual of the community.

Second objective was to understand the lifestyle of the people in relation to risk of non- communicable diseases.

Third objective was to assess for sensitivity for risk factors of non-communicable diseases.

Fourth objective was to assess on preventive methods to non-communicable diseases.

Fifth objective was to use verbal post mortem to assess for mortality caused by non- communicable disease Ethical clearance was obtained by the ethical committee.

Inform concern was obtained from individuals. Study site. Tamale and its metropolis were chosen for this study. These are major catchment areas for the hospitals TTH, Central and West hospitals. Where most of the secondary data was obtained by the retro spective study of medical records on mortality and morbidity of NCDs. Tamale is the capital town of northern region and the fastest growing city in the south Saharan Africa (UNIFEC2000). The population of tamale and its metropolis is 2.5 million (Ghana statistical Board 2007), 2010 census. The city is characterized by urban poverty, high level of pollution, illiteracy, low family planning and unplanned urbanization. The risk factors of NCDs and CDs are highly eminent and fuelled by high immigration rate by refuges from neighboring poor countries.

7. Results of Risk Factors of Non Communicable Diseases

8. Discussion of Results

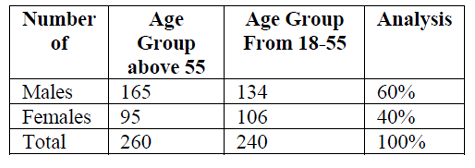

As found in table number one, 260 of the population participated in the test were of age above 55 years. This is the degenerative age. Hypertension, diabetics, stroke and other degenerative diseases are expected to be of higher risk to this group of people (WHO 2010). 165 males participated and 95 females participated. This could be because, more male’s part took in the research. 240 of the responded in the research. This people were the active and working population (18-55) years old. WHO/UN are worried of the fact that the developing world, most of this working population is destroyed by the non- communicable diseases. This is not good news because it the economy of the nation will be driven into severe poverty.

The common NCDs in the TMA as documented in the hospitals are; hypertension, diabetics, stroke, mental illness, peptic ulcer disease, COPD, CKD and CLD.

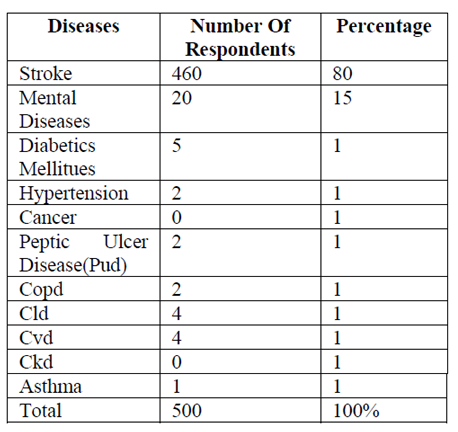

As documented in table two, 80 per cent (460) of the participants new about stroke, 15 per cent new of mental illness, less than 5 per cent new of hypertension, diabetics, COPD, CLD, peptic ulcer and CKD. The fact is that, stroke as explain in medical literature is a result complication of hypertension, diabetics, CKD or CLD. The respondent has no knowledge of this conditions and yet have alluded to the fact that people with the sign and symptoms of strokes are more.

Common in their localities. They even have a local name for stroke because that is the common NCDs they know most. (Stroke is called gbalinibogu in the local dilect of Tamale.

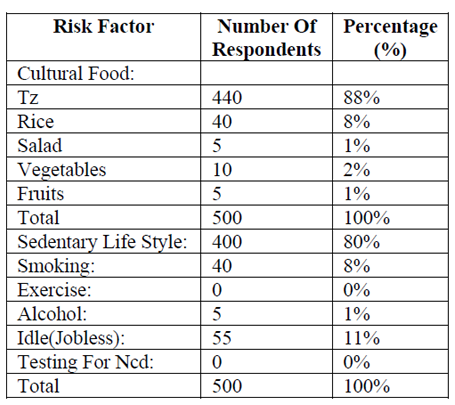

Mental illness is the second most commonly known NCD in the TMA. This, medically, is supposed to be terminal complication of conditions like; depression, illness, alcoholism, stress, and other negative life styles. The respondents see and know about these complications, but do no check for and do not know about the conditions leading to those conditions. The WHO have documented, that four of every five die of NCD in south Saharan Africa. 63% of all deaths wold wide are caused by NCD (UN economic summit, 2013). As documented in table 3, 0% Of the respondents is doing checkup for DM. Hypertension or even exercising. This is a tip of an ice burg. Many people have the condition, but do not know until complication set in.

The risk factors for NCD are sedentary life, cultural food, smoking and old age. Table #3. The most commonly known NCD at the TMA are stroke and mental illness, which are rather Complications of DM Hypertension, and depression.

9. Discussion

Diabetes: The problem is still far from over; because according to our research findings, the people of Tamale Metropolitan Area are yet uninformed of the non-communicable disease because they are silent killers. The signs and symptoms are not eminent; they can only be detected by preempted medical or laboratory checkups. Meanwhile this is not the culture of the inhabitants of Tamale Metropolitan area.

Stroke: Magnitude of research problem is found in the fact that almost everybody answered yes to question; do you know somebody who suffering from stroke (Gbalnibogu) meaning hemi paralysis of motor systems. This is supposed to be as a result complication diabetes mellitus and uncontrolled hypertension. If the prevalence of stroke is so high in the system, then the massage is that a higher population of the Tamale Metropolitan area are living or dying with undetected diabetes mellitus cancer and all other non-communicable diseases.

As seen in the picture above the woman is suffering from depression this can lead to mental diseases. It leads to neglect of motherhood duties.

Mental diseases (Yibilsi): is the next most common disease in the Tamale Metropolitan area. The WHO documented in world economic summit report that USD 61.1 trillion will be needed to resolve mental health conditions. The unplanned urbanization in the city explains the high prevalence of mental diseases as documented in our results. This goes in line with WHO (2011) findings that the creation of urban slams is mathematically related to the prevalence of mental diseases such as schizophrenia, depression and maniac diseases.

Question; do you know anybody with mental disease? Was answered yes by more than sixty percent of the respondents. If mental diseases such as schizophrenia are complications of depression, drug abuse and other non- communicable diseases and life style diseases then the massage is that there are more undetected conditions of neuro psychotropic in the population of the Tamale Metropolitan area.

More research and community based investigations need to be carry out in this population to reduce poverty and under development. Public health and institutional education on these killer diseases is not an option but a necessity, inevitable.

10.Conclusions

There is a higher prevalence of non- communicable diseases at the TMA. No physical or laboratory checkup is done. Patients are not diagnosed, are not treated until complications set in.

Diabetes and hypertension do not have eminent physical signs and symptoms, thus are silent killers which are not known by the population of the TMA. Stroke and mental illness have eminent signs and symptoms that are identifiable by the general population. Paralysis of the limbs and loss of mental control.

11.Recommendation

For prophylactic against risks factors lay knowledge is very necessary. Education is therefore not an option health education at all levels of our education institution must be aware of NCDs, not only aware but knowledgeable about these diseases of burden in the country. Public health education has to be continues on all our media including; radio and television and even at the religious centers. Compulsory medical checkup at all government set ups (institution and work places). All diagnosed shall be assisted in treatment. Drama groups in our local diet could be trained and used to educate the illiterate communities on NCDs so that they can prevent the diseases by avoiding the risk factors.

References

- Appel LJ, Obarzanet E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, et al, A clinical trial of the effects dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336: 1117-1124.

- Beaglehole R. Global cardiovascular disease prevention: time to get serious. Lancet.2001; 358:661663.

- Bonita R. WR, Douglas K. The WHO STEP wise approach to NCD risk factor surveillance. Cordrecht: Kluwer, 2001.

- Brown MJ. Hypertension and ethnic group. Bmj.2006; 332:833-836.

- Burket BA. Blood pressure survey in two communities in the Volta region, Ghana, West Africa.Ethn Dis. 2006; 16:292-294.

- Cappuccino FP, Kerry SM, Micah FB, Plange- Rhule J, Eastwood JB. A community programme to reduce salt intake and blood pressure in Ghana BMC Public Health. 2006; 6:13.

- Cappuccio FP, Micah FB, Emmett L, Kerry SM, Antwi S, Martin-Peprah R, et al. Prevalence, detection, management, and control of hypertension in Ashanti, West Africa. Hypertension 2004; 43:1017-1022.

- Chobanian AV, Control of hypertension an important national priority. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:534-535.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr., et al. The seventh Report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of High Blood Pressure.

- Duda RB, Kim MP, Darko R, Adanu RM, Seffah J, Anarfi JK, et al. Results of the Women’s Health Study of Accra: assessment of blood pressure in urban women. Int J Cardiol. 2007; 117:115-122. Retrospective Study of Records on Epidemiological Transition in the Tamale Teaching Hospital International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE)

- Kunutsor S, Powless J. Descriptive epidemiology of blood pressure in a rural adult population in northern Ghana. Rural Remote Health.2009; 9:1095.

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projection of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030.PLoS Med. 2006; 3:e442

- Mendis S, Yach D, Bengoa R, Narvaez D, Zhang X. Research gap in cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Lancet 2003; 361:2246-2247.

- Mensah GA. Epidemiology of stroke and high blood pressure in Africa Heart. 2008; 94:697- 705

- Ministry of Health, The Ghana Health Sector 2006 Programme of Work. 2005

- National High Blood Pressure Education Programme Working Group report on primary prevention of hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1993; 153:186-208.