Information

Journal Policies

Sacral Osteoid Osteoma: A Rare Cause of Back Pain in Childhood

Mohamed Ali Khalifa

Copyright : © 2019 Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction: Osteoid osteoma is an uncommon benign bone tumour. It develops in young people and involves their long bones, especially lower extremities. The affection of vertebral column is rare (10%) and sacrum is exceptionnally affected (2%). Osteoid osteoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any young patient with back pain. The tumor is the most common cause of painful scoliosis in young patients. In spite of typical symptoms the diagnosis is often delayed.

Case Report: We report a case of a 6-year-old student girl who complained of chronic back pain worsening at night with non radicular left leg pain for several months duration and with no response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). The physical examination objectived no temperature, no gibbosity, no limping, just a pressure tenderness of the sacral region. Biology and radiography of the pelvis was both normal. The CT scan and MRI showed a subperiosteal nodule with intra and extra development on S2 left lamina evoking osteoid osteoma.

The patient went under a surgical excision through a posterior approach and intralesionnal excision of the nidus with minimal removal of bone.

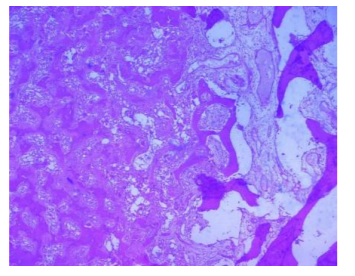

The histological study confirmed the osteid osteoma with a broad bony trabecular mesh and a small fibrovascular component identified in its central area. Complete resolution of back and leg pains was obtained within a short period and no recurrancy noticed at last follow-up.

Conclusion: Osteoid osteoma is a relatively frequent benign bone tumor of osteoblastic origin. Atypical manifestations of osteoid osteoma are prone to diagnostic and therapeutic delays and errors and may cause diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties.

osteoid osteoma - sacrum- bone tumour- child,Orthopedics

1. Introduction

Osteoid osteoma is a relatively uncommon benign bone tumor, accounting for 12% of all benign bone tumors and about 2 to 3% of all bone tumors. It particularly affects young people with male predominance. Its location in the skeleton is essentially femoral and tibial diaphyseal.

The affection of vertebral column is rare (10%) and sacrum is exceptionnally affected (2%). Osteoid osteoma should be included in the differential diagnosis of any young patient with back pain. The tumor is the most common cause of painful scoliosis in young patients. In spite of typical symptoms the diagnosis is often delayed.

2. Observation

We report a case of a 6-year-old student girl who complained of chronic back pain worsening at night with non radicular left leg pain for several months duration and with no response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). The physical examination objectived no temperature, no gibbosity, no limping, just a pressure tenderness of the sacral region.

Biology and radiography of the pelvis was both normals.

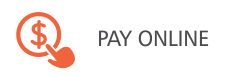

The CT-scan showed an extensive lesion in left lamina of S2 with a form of a nidus and a peripheric osteosclerosis which compressed the left S2 root (figure 1,2).

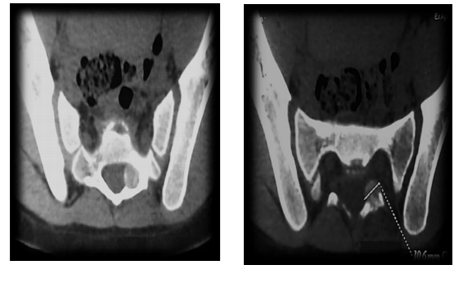

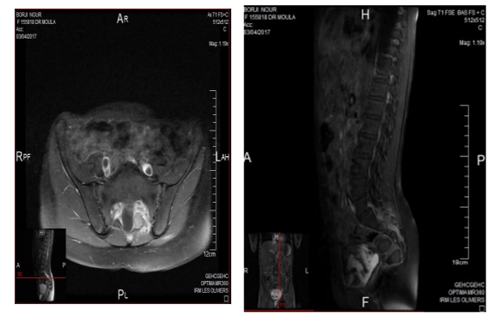

In the MRI, we noted a Subperiosteal nodule with intra and extra development on S2 left lamina with calcifications. It have an hyposignal T1and an hypersignal T2 with enhancement after injection of gadolinium. (figure 3,4).

The patient went under a surgical excision through a posterior approach and intralesionnal excision of the nidus with minimal removal of bone.

The histological study confirmed the osteid osteoma with a broad bony trabecular mesh and a small fibrovascular component identified in its central area (figure 5).

Complete resolution of back and leg pains was obtained within a short period and no recurrancy noticed at last follow-up.

3. Discussion

Décrit pour la première fois par Jaffe en 1935 [1], l’ostéome ostéoïde est relativement fréquent : il représente 2 a 3 % de l’ensemble des tumeurs osseuses et 10 a 20 % des tumeurs bénignes [2]. Sa pathogénie est controversée [3,4]. En effet il se caractérise par un nidus trés innervé et hyper vascularisé entouré d’une ostéogenèse réactionnelle périphérique. Au niveau du nidus a été observée une libération importante de prostaglandine responsable de la douleur, expliquant ainsi la régression de cette douleur a l’administration de l’aspirine.

L’ostéome ostéoïde est une tumeur du sujet jeune : 2/3 s’observent chez l’enfant et l’adolescent (avec un pic entre 10 et 20 ans) et 1/3 chez l’adulte jeune avec un sex ratio de 2 a 3 garçons pour une fille[2]. Son siège le plus fréquent est la diaphyse fémorale ou tibiale (75%)[5]. The spine is one of the common locations of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma (12 %-37 %). As compared with other spine segments, the sacrum is rarely affected (7 %-12 %) [6]. Osteoid osteomas of the sacrum in particular were rarely observed.

Sur le plan clinique, l’ostéome ostéoide se manifeste par une douleur localisée a paroxysme nocturne. Cette douleur se caractérise par sa rétrocession a l’administration d’aspirine ou d’AINS. Pour notre patient, le tableau clinique est caractérisé essentiellement par des lombalgies chroniques d’aggravation nocturne non améliorées par les AINS.

In the sacrum, when S 1 is involved a marked spinal stiffness is usually present (60 %); in contrast, spinal stiffness is rare when the lesion spares S-1 (20 %). Neurological symptoms are rare (30 %); they are usually found in lesions more than 2 cm in diameter [7]. Scoliosis is usually present in lesions eccentrically involving either the body or the posterior elements of S-1. When the lesion is located centrally in S-1 or spares it, scoliosis is rare [8].

Les radiographies standard ne permettent toujours d’affirmer le diagnostic. Le nidus n’est pas le plus souvent visible. Il faut cependant le rechercher au sommet de la courbure rachidienne, sur le rachis ou même au-dela sur la côte en regard par exemple.

CT is particularly useful for characterizing spinal osteoid osteomas. These lesions typically manifest as low-density nidi in the posterior elements. Many studies have cited the superiority of CT over MRI in both diagnosing and characterizing osteoid osteomas [9,10]. Technetium-99–labeled bone scintigraphy may prove useful for confirming the diagnosis with a 100% virtual sensitivity for detection [11].

Classically, the correct surgical treatment is to expose and curette the nidus by the gradual excision of minimal reactive bone. This ensures removal of the entire lesion, without recurrence with no need for internal fixation or bone grafts. Postoperative mobilisation is immediate with early recovery of full function unlike the wide en-bloc resection. Ce traitement est actuellement de plus en plus souvent effectué par voie percutanée, sous contrôle tomodensitométrique [12]. Le geste ne doit pas être trop limité pour éviter l’exposition au risque de récidive. Le repérage scanographique permet un abord réduit, avec un sacrifice osseux limité. La photocoagulation au laser a été utilisée, car elle détruit par chauffage la tumeur dans un volume millimétrique autour de l’extrémité de la fibre. Nous avons préféré un abord a foyer ouvert par voie postérieure directe, avec une résection du nidius.

4. Conclusion

Osteoid osteoma is a relatively frequent benign bone tumor of osteoblastic origin. Multicentric, intra- or juxta-articular, medullary and sub-periosteal lesions are called atypical osteoid osteoma. Atypical manifestations of osteoid osteoma are prone to diagnostic and therapeutic delays and errors and may cause diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties. Perfunctory diagnosis and treatment of lesion may cause recurrences, repeat procedures and may be overtreatment such as unnecessary resections.

References

- Bonnevialle P, Railhac JJ (2001) Oste´ome osteoide, osteoblastome. Encycl Med Chir Appareil Locomoteur 7: 14-17

- Becce F, Theumann N, Rochette A, Larousserie F, Campagna R, Cherix S et al. Osteoid osteoma and osteoid osteomamimicking lesions: biopsy findings, distinctive MDCT features and treatment by radiofrequency ablation. Eur Radiol. 2010; 20(10):2439-46. PubMed | Google Scholar

- Muller PY, Carlioz H (1999) Re´cidive ou persistance d’un oste´ome oste´oı¨de : une observation. Rev Chir Orthop 85: 69-74

- Weber KL, Morrey BF (1999) Osteoid osteoma of the elbow: a diagnostic challenge. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81(8): 1111-9

- Shereff MJ, Cullivan WT, Johnson KA (1983) Osteoid osteoma of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg 65A: 638-41

- Jackson RP, Reckling FW, Mants FA. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma: similar histologic lesion with different natural histories. Clin Orthop 1977;128:303-13.

- Themistocleous GS, et al. (2006) Osteoid osteoma of the upper extremity: a diagnostic challenge. Chir main 25: 69-76

- Lee EH, Shafi M, Hui JH.: ” Osteoid osteoma: a current review” J Pediatr Orthop. 2006 Sep-Oct;26(5):695-700.

- Themistocleous GS, et al. (2006) Osteoid osteoma of the upper extremity: a diagnostic challenge. Chir main 25: 69-76

- Kreitner KF, Low R, Mayer A. Unusual manifestation of the osteoide osteoma of the capitate. Eur Radiol 1999;9: 1098-100.

- Wells RG, Miller JH, Sty JR. Scintigraphic patterns in osteoid osteoma and spondylolysis. Clin Nucl Med 1987; 12:39–4

- Donahue F, Ahmad A, Mnaymneh W, Pevsner N. Osteoid osteoma. Computed tomography guided percutaneous excision. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;366:191-6.