Information

Journal Policies

Bleeding Gastric Varices: Frequency and Outcome

Khairy H. Morsy1*, Asmaa N. Mohammad1, Mahmoud K. El-Samman2, Walaa A. Ali1

2.Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Sohag University, Sohag, Egypt

Copyright : © 2018 . This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background and aims: Gastric variceal bleeding is less frequent than esophageal varices bleeding but it still a serious cause of morbidity and mortality. The aim of study was to assess the frequency and identify the patients' outcome after management.

Patients and methods: The study was conducted on cirrhotic patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the period from June 2016 to June 2017 who underwent esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy&subjected to complete history taking, clinical examination, laboratory investigations & abdominal US.

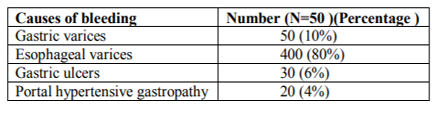

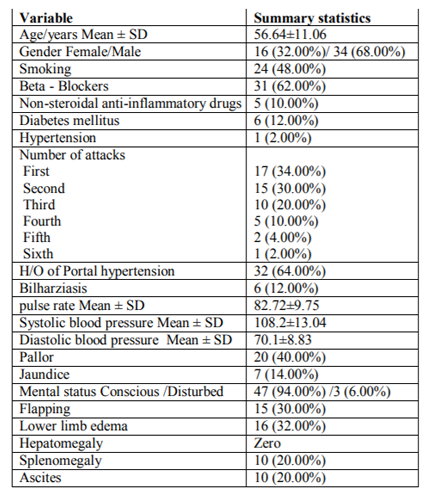

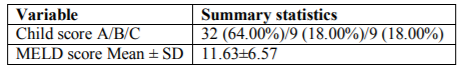

Results: The study included 500 patients. In the endoscopic findings, bleeding from gastric varices (GV) was seen in 50 patients (10 %), bleeding from esophageal (EV) was detected in 400 patients (80 %), while bleeding from other sources was in 50 patients (10%).The mean age of GV patients was 56.64± 11.06; most of them were males 34 (68 %)& the most common etiology of the underlying liver cirrhosis& portal hypertension was HCV that was detected in 40 patients (80%).Only 35 patients (70%) had isolated GV type I & 15 patients (30%) had continuous Gastroesophogeal varices type 2 with red colour signs (Rc+) in 80% of the cases.PHG was seen in 48 patients(96%).Bleeding was more common between Child A patients although it was not significant. Also there were no significant differences between grades of gastric varices according to MELD score. As regards the outcome, 40% developed eradication, 38% died & 22% developed re-bleeding. Upon studying the predictors of mortality, we found that they had significantly lower albumin & higher ALT & AST levels. Early re-bleeding was more common among child A patients with moderately sized GV (F2), but the difference was not statistically significant. By multivariate analysis we found that were no independent predictors of rebleeding gastric varices.

Conclusion: frequency of bleeding GV was 10% among cirrhotic patient with upper GIT bleeding. No independent factors could predict the mortality or rebleeding among cirrhotic patients with bleeding GV by multivariate analysis.

Gastric varices, Esophageal varices, Bleeding, Gastroenterology

1. Introduction

Acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common cause of emergency hospitalization worldwide1.Acute variceal hemorrhage (AVH) is an important complication of portal hypertension (PH) that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality2. Gastric variceal bleeding is a serious cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with PH. Most of the studies underestimate their true prevalence3. It may be difficult to distinguish fundal varices from gastric folds due to their deep submucosal location as well as the normal color and appearance of the overlaying mucosa4.The prevalence of gastric varices (GV) in patients with PH varies from 18 to 70%; although the incidence of bleeding from GV is relatively low ranging from 10 to 36%. Management of GV presents a challenging problem, because since there is no consensus regarding the optimum treatment of GV, treatment tends to be empirical5.Sarin et al 6., documented that GV were found in 20% of patients with PH and secondary GV developed in 9% of patients during follow-up evaluation.

Although GV bleeding occurs less frequently than esophageal varices (EV) bleeding; it tends to be more severe and requires more blood transfusions with a higher mortality than EV bleeding6. Red color spots, larger nodular gastric varices, and fundal location have been identified as risk factors for GV bleeding7. In addition, Kim et al8. Found that advanced Child-Pugh class, varix>5 mm in size, and the presence of a red spot were associated with an increased risk for a first bleed. As a result of the high morbidity and mortality of GV, it is valuable to estimate its exact frequency and identify risk factors for bleeding among upper Egyptian patients. In addition, evaluation of GV outcome after GV injection.

2. Aim Of The Work

The aim of study was to assess frequency of bleeding GV and identify the patients' outcome after management.

3. Patients & Methods

This prospective clinical study was conducted on all cirrhotic patients with upper GIT bleeding seeking medical advice at the Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology Department, Sohag University Hospital in the period from June 2016 to June 2017.

Patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension underwent EGD after upper GIT bleeding at the Tropical Medicine and Gastroenterology Department, Sohag University Hospital and diagnosed to have bleeding gastric varices.

Patients diagnosed to have other causes of upper GIT bleeding (such as: EV, peptic ulcer disease, reflux esophagitis, erosions, antral vascular ectasia).

All patients will be subjected to the following:

1- Complete clinical evaluation.

2- Laboratory Investigation: Complete blood picture, Liver profile serological testing for HBV, and HCV, Serum Creatinine, Ascitic fluid study.

3- Abdominal Ultrasonography :With details about Size of the liver, surface, hepatic focal lesion, portal vein diameter, portal vein thrombosis, Spleen size, & porto-systemic collaterals and ascites.

4- Upper GIT endoscopy: Upper endoscopic examination for detailed evaluation of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum.

4. Ethical Consideration

The study design was approved by the ethical and scientific research committee of Faculty of Medicine, Sohag University. Informed consents were obtained from all patients.

5. Results

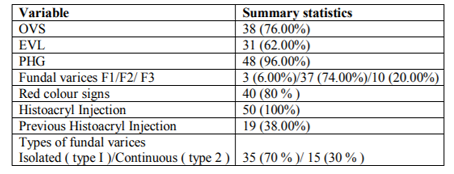

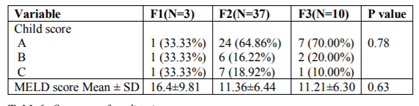

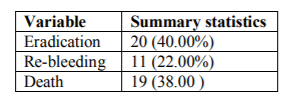

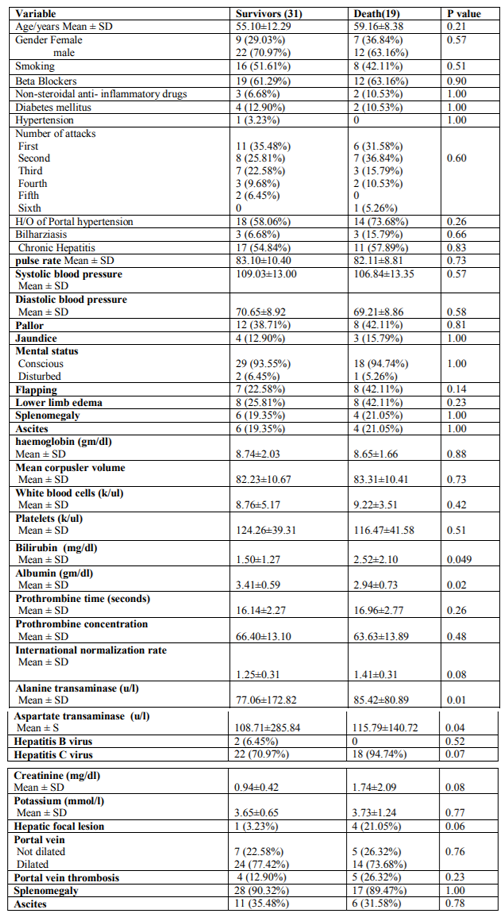

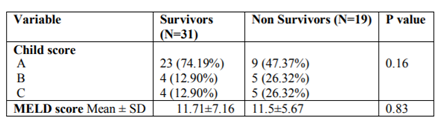

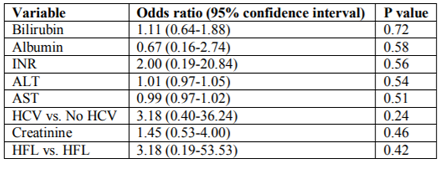

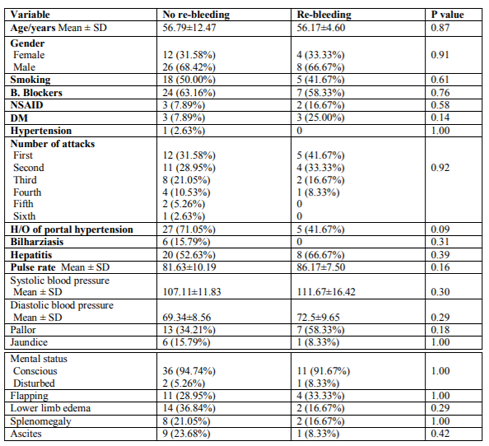

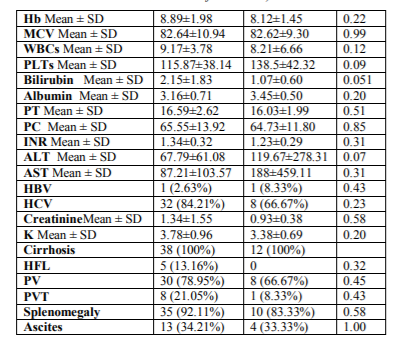

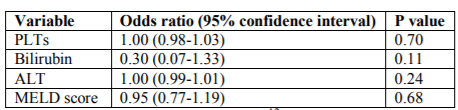

In the endoscopic findings, bleeding from gastric varices was seen in 50 patients (10 %) , bleeding from esophageal varices was detected in 400 patients (80 %), while bleeding from other sources (non variceal _ bleeding) was in 20 patients (4%) as shown in Table (1) .The mean age of the studied population was 56.64± 11.06, most of them were males 34 (68 %) Table (2).The most common etiology for the liver cirrhosis & portal hypertension of the studied group was HCV which was detected in 40 patients (80%) While HBV was detected in 2 patients only (4%) as shown in Table (2). Primary hemostasis was achieved in all patients with histoacryl injection. Only 35 patients (70%) had isolated GV type I & 15 patients (30%) had continuous Gastroesophogeal varices type 2 with red colour signs (Rc+) in 80% of the cases. Bleeding from OVS was in 38 patients (76%) & thoses who underwent band ligation were31 patients (62%).PHG was seen in 48 patients (96%) as shown in Table (4). Bleeding was more common between Child A patients but there were no significant differences as regard child classification or size of varices, also MELD score as shown in Tables (3), (5). Rate of rebleeding was (22%) , deaths occurred in 19 patients (38%) after admission & eradication of GVs were achieved in 20 (40%)Table(6).Upon studying the predictors of mortality, we found that they had significantly lower albumin & higher ALT & AST levels with no significant difference as regard ultrasonograghic findings Table (7). Regarding to child classification & MELD score we found no significant difference between the two groups and these scores could not predict the mortality in our Patients Table (8).By multivariate analysis we found no independent predictors of mortality or rebleeding in cirrhotic patients with gastric varices as shown in Table (9) & (12).

6. Discussion

In our present study, frequency of bleeding gastric varices was 10 %, frequency of esophageal bleeding was 80% while non- variceal bleeding (gastric ulcers & PHG) represented only 10% .Similar studies reported that gastric varices (GV) are responsible for 10- 30% of all variceal hemorrhage9.

In another study, Gastric varices are responsible for about 10% of variceal bleeding; however, they are also the cause of massive haemorrhage, often with dramatic progress10 .Recently, Mumtaz and his collages (in Pakistan) reported that the overall prevalence of gastric varices among their patients was 15% 11.Another prospective observational study in which 589 UGIB patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy from May 2010 to April 2013 in Nepal. Among UGIB patients, 33.1 % were variceal and 66.9 % were non-variceal bleeding (peptic ulcers 23.9 %, gastric erosion 16.5 % and others) 12. The mean age of the studied population was 56.64± 11.06 year, most of them were males 34 (68 %). In another study, out of 205 patients undergoing esophago- gastroduodenoscopy, 122(59.5%) were male and 83(40.5%) were female with an overall mean age of 49.5+/-7.49 years13.While a total of 41 patients (39 with cirrhosis) underwent 54 cyanoacrylate injections during study period. Mean age was 57 and 73 % were males14.It was found by our study that the most common etiology of portal hypertension which led to GV bleeding was liver cirrhosis (100%).Another observationalcross-sectionalstudywas conducted from August 2014 to August 2015 at Aziz Bhatti Shaheed Teaching Hospital, Gujrat, Pakistan, using non-probability consecutive sampling. Patients having liver cirrhosis only due to chronic hepatitis C virus, portal vein diameter >12mm or spleen size >12cm in long axis and ascites with no previous history of variceal banding were included. Out of 205 patients undergoing esophago-gastroduodenoscopy, 122(59.5%) were male and 83(40.5%) were female with an overall mean age of 49.5+/-7.49 years. Gastric varices were present in 30(14.6%) patients13 and between January 1998 and January 2010, 97 patients with gastric variceal bleeding underwent endoscopic treatment with a mixture of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and Lipiodol , ninety-one patients had cirrhosis and 6 had non-cirrhotic portal hypertension15.The medical records of patients who presented with active gastric variceal bleeding between 1998 and 2011 in a tertiary care setting were evaluated retrospectively and the eventual outcome(s) (initial hemostasis, rebleeding, and mortality rate) was assessed at least 1 year after the index bleed ( ninety-seven patients were included) , the mean age of the patients was 51.0 +/- 12.5 years; 62% were men.

Hepatitis C was the most common etiology, found in 63 (65%) patients16. Our present study showed that the population study who underwent EGD had EV (76%), moderately filled bleeding GVs (74%).Isolated gastric varices type 1& gastroesophogeal varices type 2 had higher bleeding incidence ( 70% , 30% ) respectively .Similar results were reported by Sarin et al., 6 where isolated gastric varices type 1 and gastroesophageal varices type 2 had a significantly higher bleeding incidence (78% and 55% respectively), than gastroesophageal varices type 1 and isolated gastric varices type 2 (10%).However,Mumtaz et al., 11reported that the incidence of bleeding from isolated gastric varices type 1 was 36% and from gasroesophageal varices type 1, gasroesophageal varices type 2 and isolated gastric varices type 2 were 17.7%, 20.5% and 0% respectively. .Butt et al., 13 show that gastric varices were present in minority of patients undergoing esophago- gastroduodenoscopy, and among them gastroesophageal varices type 1 was the most common, while isolated gastric varices type 2 was not present in any patient .Other similar results from Egypt were reported by Thakeb and his college, where isolated gastric varices were accounting for 7.2% and gastroesophageal varices were accounting for 27.1%17 .In our study, there was also a relation between bleeding from isolated gastric varices and endoscopic signs where bleeding was more in patients with red color signs as reported in 80 % of the cases .The same results were reported by others where they found a significant relation between bleeding from gastric varices and the presence of red color signs18 . However, there was non statistically significant relation between bleeding gastric varices , MELD & Child scores where bleeding was more in patients with Child class A . This was attributed to small number of the studied population ( 50 patients ) & also limited duration of the study through which data were obtained .This was against other studies , such as the results which were reported by Kim et al., 19978where bleeding from gastric varices was more common in patients with Child class B and C (80% of bleeder) than in patients with Child class A (20% of bleeders) and also that difference was statistically significant. Another author reported Child-Pugh score at presentation for cirrhotic patients was A-12.1 %, B-53.8 %; C-34.1 % and median MELD score at admission was 13 (3-26)15 . Child-Pugh classification was a significant prognostic factor of survival (P< 0.001)16, While other reports failed to find a significant relation between bleeding from gastric varices and the severity of liver dysfunction11. There were no definite risk factors for bleeding GV as our study didn’t have control group to identify them by comparison with the study group, while other studies had. The presence of (ulcers and red color sings) and severe liver dysfunction (Child class B and C) were found to be independent risk factors for bleeding from GV regardless their type, there are many studies reported the same risk factors for bleeding from gastric varices but with minimal differences in between them8. In our present study, 40% of the studied population developed eradication 38% died & 22% developed re-bleeding .Histoacryl injection achieved Successful primary hemostasis in all patients with bleeding gastric varices and early rebleeding occurred in only 11 cases (24%).

Secondary hemostasis was achieved in all of them using N-butyl 2 cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) with no serious complications have been reported. Mumtaz et al., 200711 reported that primary hemostasis was achieved with histoacryl injection in 100% of patients and early rebleeding rate was 14%.Mortality was less than our study in others such there were 132 patients with acute GVB (83.3% men, median age 51.3 years) with endoscopic NBC injection treatments recruited. Mortality within 6 weeks was noted in 16.7% patients19.In another study, a total of 20 patients (15 male) with PH and GV were enrolled and treated with undiluted NBC injection. The patients were followed clinically and endoscopically for a median of 31 months. Eradication of GV was observed in all patients (13 patients were treated with 1 session and 7 patients with 2 sessions).Overall, GV recurrence was observed in 2 patients (10%), after 6 and 35 mo of follow-up, and GV bleeding rate was 5% (1 patient) 20 .Upon studying the predictors of mortality, we found that they had significantly lower albumin & higher ALT & AST levels with no significant difference as regard ultrasonograghic &endoscopic findings. Regarding to child classification & MELD score we found no significant difference between the two groups and these scores could not predict the mortality in our patients. Impaired renal function, deteriorated liver function with Child pugh score>/= 9 as well as MELD score >/= 18, rebleeding within 5 days, and acute on top liver cell failure are independent predictors of mortality19 .we found in our study thatearly re-bleeding was more common among child A patients with moderately sized GV (F2), but the difference was not statically significant &by multivariate analysis we found that were no independent predictors of rebleeding gastric varices.

Other studies reported that predictors for rebleeding are usually related to the severity of the bleeding and characteristics of the ulcer, whereas advanced age, physical status of the patient, and comorbidities are important predictors for mortality in addition to those for rebleeding21.Patients with AVH and MELD score >or = 18, requiring > or = 4 units of PRBCs within the first 24 h or with active bleeding at endoscopy are at increased risk of dying within 6weeks. MELD score > or = 18 is also a strong predictor of variceal re-bleeding within the first 5 days22.

Another study reported that re-bleeding within 5 days occurred in 37 patients (15%), MELD score (p = 0.01) and a clot on a varix (p = 0.05) predicted re-bleeding. Patients with a MELD score > or = 18; both MELD score > or = 18 and > or = 4 units of PRBCs transfused; both MELD score > or = 18 and active bleeding at index endoscopy; and variceal re-bleeding had increased risk of death 6 weeks post-AVH22.

7. Conclusion

No independent factors could predict the mortality or rebleeding among cirrhotic patients with bleeding GV by multivariate analysis.

References

- Kapsoritakis AN, Ntounas EA, Makrigiannis EA, Ntouna EA, Lotis VD, Psychos AK, Et al: Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in central Greece: the role of clinical and endoscopic variables in bleeding outcome. Digestive diseases and sciences. 54(2):333-41(2009) .

- Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L, Fourdan O, Levy VG, Poupon R. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 40(3):652-9 (2004) .

- BM Ryan, RW Stockbrugger, JM Ryan – Gastroenterology. Pathophysiologic , gastroenterologic and radiologic approch to mangement of gastric varices.126(4) : 1175-1189.(2004)

- Sanyal AJ. The value of EUS in the management of portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc.52:575–7 (2000) .

- Tajiri T, Onda M, Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Yamashita K. The natural history of gastric varices. Hepatogastroenterology. 49: 1180-2 (2002).

- Sarin, S. K. & Lahoti, D. Management of gastric varices. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol, 6, 527-48(1992 ) .

- Hashizume, M., Kitano, S., Yamaga, H., Koyanagi, N. & Sugimachi, K. Endoscopic classification of gastric varices .Gastrointest Endosc, 36, 276-80 (1990) .

- Kim, T., Shijo, H., Kokawa, H., Tokumitsu, H., Kubara, K., Ota, K., Akiyoshi, N., Iida, T., Yokoyama, M. & Okumura, M. Risk factors for hemorrhage from gastric fundal varices. Hepatology, 25, 307-12 (1997) .

- Wani, Z. A., Bhat, R. A., Bhadoria, A. S., Maiwall, R. & Choudhury, A Gastric varices: Classification, endoscopic and ultrasonographic management. J Res Med Sci, 20, 1200-7(2015).

- Koziel, S., Kobryn, K., Paluszkiewicz, R., Krawczyk, M. & Wroblewski, T. Endoscopic treatment of gastric varices bleeding with the use of n-butyl-2 cyanoacrylate. Prz Gastroenterol, 10, 239-43 (2015) .

- Mumtaz, K., Majid, S., Shah, H., Hameed, K., Ahmed, A., Hamid, S. & Jafri, W. Prevalence of gastric varices and results of sclerotherapy with N-butyl 2 cyanoacrylate for controlling acute gastric variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol, 13, 1247-51 (2007) .

- Shrestha, U. K. & Sapkota, S. Etiology and adverse outcome predictors of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in 589 patients in Nepal. Dig Dis Sci, 59, 814-22 (2014) .

- Butt, Z., Ali Shah, S. M., Afzal, M., Younis, I., Waqas, M. & Atta, H. Frequency of different types of gastric varices in patients with cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C. J Pak Med Assoc, 66, 1462-1465 (2016) .

- Kahloon, A., Chalasani, N., Dewitt, J., Liangpunsakul, S., Vinayek, R., Vuppalanchi, R., Ghabril, M. & Chiorean, M. Endoscopic therapy with 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate for the treatment of gastric varices. Dig Dis Sci, 59, 2178-83 (2014) .

- Monsanto ,P., Almeida, N., Rosa, A., Macoas, F., Lerias, C., Portela, F., Amaro, P., Ferreira, M., Gouveia, H. & Sofia, C. Endoscopic treatment of bleeding gastric varices with histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate): a South European single center experience .Indian J Gastroenterol, 32, 227-31 (2013) .

- Khawaja, A., Sonawalla, A. A., Somani, S. F. & Abid, S. Management of bleeding gastric varices: a single session of histoacryl injection may be sufficient. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 26, 661-7 (2014) .

- Thakeb, F., Salem, S. A., Abdallah, M. & El Batanouny, M. Endoscopic diagnosis of gastric varices. Endoscopy, 26, 287-91(1994) .

- Joshi, N. G. & Stanley, A. J. Update on the management of variceal bleeding. Scott Med J, 50, 5-10(2005).

- Teng, W., Chen, W. T., Ho, Y. P., Jeng, W. J., Huang, C. H., Chen, Y. C., Lin, S. M., Chiu, C. T., Lin, C. Y. & Sheen, I. S. Predictors of mortality within 6 weeks after treatment of gastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Medicine (Baltimore), 93, e321 (2014).

- Franco, M. C., Gomes, G. F., Nakao, F. S., De Paulo, G. A., Ferrari, A. P., JR. & Libera, E. D., JR. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic prophylactic treatment with undiluted cyanoacrylate for gastric varices. World J Gastrointest Endosc, 6, 254-9(2014).

- Chiu, P. W. & NG, E. K. Predicting poor outcome from acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 38, 215-30 (2009) .

- Bambha, K., Kim, W. R., Pedersen, R., Bida, J. P., Kremers, W. K. & Kamath, P. S. Predictors of early re-bleeding and mortality after acute variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Gut, 57, 814-20(2008) .