Information

Journal Policies

ARC Journal of Clinical Case Reports

Volume-2 Issue-2, 2016, Page No: 1-2

Granulomatous Rosacea- A Case Report

Zuzana Nevoralová¹, Lumír Pock²

1.Dermatovenereologic Department, Regional Hospital Jihlava Vrchlického 59, 586 33 Jihlava, Czech Republic ; [email protected]

2.Dermato histopathological Laboratory MazurskáSt, Prague, Czech Republic ;

[email protected]

2.Dermato histopathological Laboratory MazurskáSt, Prague, Czech Republic ;

[email protected]

Citation : Zuzana N, Lumír P. Granulomatous Rosacea- A Case Report. ARC Journal of Clinical Case Reports. 2016;2(2):1–5.

Copyright : © 2016 Zuzana N. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Granulomatous (lupoid) rosacea is a rather rare form of rosacea. Clinically it is characterized by numerous brown-red papules or little nodules on a diffusely reddened, thickened skin localized mostly on the face. Epitheloid granulomas of the noncaseating type are the histopathological equivalent of these lesions, giant cells are rather rare. Multifactorial aetiology has been suggested. The disease requires special care, treatment with oral antibiotics or isotretinoin is necessary in most cases. A case of granulomatous rosacea is presented. A 58-year-old man suffered from red papules on the forehead and right cheek and slight erythema and teleangiectasias on the nose and cheeks. A therapy using peroral isotretinoin had a positive effect. No side effects of the therapy were found, and a complete healing of the papules was achieved. The patient is still being followed up; he is still undergoing a maintenance therapy and following all the rosacea protection measures.

Keywords: Granulomatous Rosacea, Lupoid, Granulomas, Peroral Isotretinoin.

Abbreviations: GR - Granulomatous (lupoid) Rosacea.

1.Introduction

Granulomatous (lupoid) rosacea (GR), considered to be a variant of rosacea, is characterized by numerous brown-red papules or little nodules on a diffusely reddened, thickened skin, frequently affecting the face. Epitheloid granulomas of the noncaseating type are the histopathological equivalent of these lesions. A managed fifty-eight with the above mentioned diagnosis is presented. GR is described in detail and special aspects of the case are pointed out.

2.The Case Report

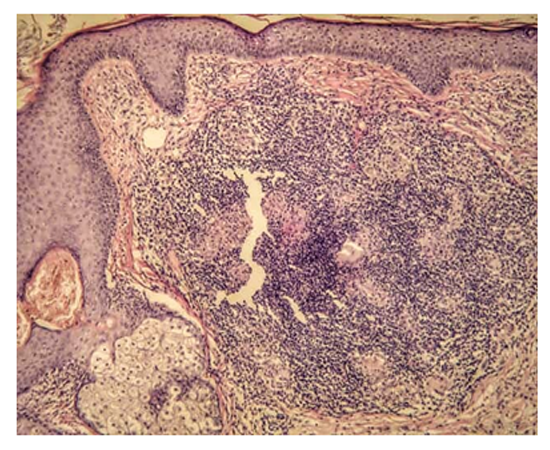

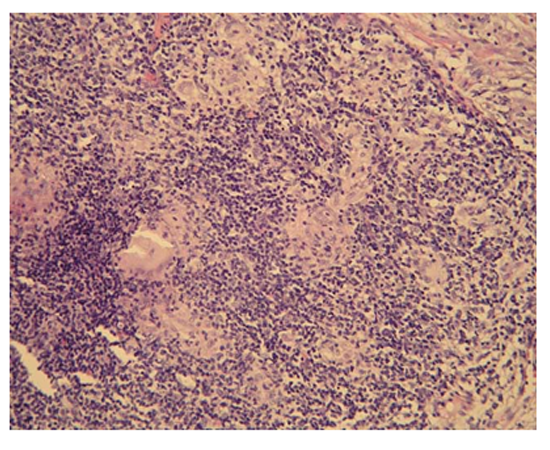

A 58-year-old man made a visit to our Acne Clinic because of papules on his face. His problems had started three months before. According to his general practitioner, a corticosteroid cream was administered locally with a transient effect. On the first visit to our Clinic the patient suffered from small non-coalescent reddish papules about three millimetres in diameter on the forehead and right cheek. No itching was recorded. The main trouble of the patient was great discomfort due to his unsightly appearance. Otherwise he was well, and no other parts of his skin were affected. He had had no history of acne, rosacea and other skin diseases; pollinosis and a slight hypercholesterolemia (treated by fenofibratum) were significant in his anamnesis. The rest of the patient’s medical history was not relevant. Supposing the possible diagnosis of eczema-dermatitis, local tacrolimus was administered twice daily and a strict photoprotection was recommended. One month later the papules reduced in size, particularly on the right cheek. Surprisingly, though, three weeks after that, the local finding was worse. The papules on the patient’s forehead enlarged (back to the diameter of three millimetres) and a slight erythema and teleangiectasias on the nose and cheeks appeared. Only small reddish papules were still present on the patient’s right cheek (figure. 1). The tacrolimus treatment was discontinued and a biopsy of one of the forehead papules was performed (figure. 2). Histopathological examination revealed a group of small lupoid granulomas in the upper half of the dermis. They were formed by epitelioid macrophages with a few multinucleated Langhans cells. The granulomas had no central necrosis and were surrounded by a dense lymphocytic infiltrate (figure. 3, 4). The diagnosis of GR was established. Next, an ophthalmological investigation was carried out, and ocular rosacea was excluded. A retinoid therapy was decided on. The laboratory tests were within normal limits except for slightly elevated low fraction of cholesterol (2,66 mmol/ l). Informed consent was signed and isotretinoin therapy at a dose of 0,3 mg/kg body weight per day was begun. Follow-up visits were chosen on monthly basis. There was a rapid therapeutic response with significant improvement (reduction of the papules in size) within one month (figure. 5). Four months later the papules completely disappeared. Isotretinoin was given at the total dose of 70 mg/ kg body weight (for six months). No side effects except for slight cheilitis and xerophthalmia, and insignificantly elevated low fraction of cholesterol (3,36 mmol/l at the maximum) were recorded. At the end of the isotretinoin treatment, only small redness and slight teleangiectasias on the nose and cheeks were still present (figure. 6). The patient is still in a follow-up of our Acne Clinic, he is very happy with his appearance. He is applying a local cream containing azelaic acid by now (as a maintenance therapy) and trying to avoid triggering factors of rosacea. The patient is regularly checked-up by an ophthalmologist.

3.Discussion

Rosacea is a relatively common chronic skin disorder which predominantly affects the central area of the face (cheeks, chin, nose and forehead). It is characterized by facial redness (in recurrent episodes or permanently), later it is complicated by the presence of papules, pustules, teleangiectasias and tissue fibrosis, sometimes also by oedema [1]. Women between 30 and 60 years of age of phototype II, Celtic types, are frequently affected by this disease. At men more serious forms with tissue hypertrophy are often present. The cause of this disease has not been fully clarified yet. As for the pathogenesis of rosacea (and also GR), many factors are discussed: neurovascular dysregulation, neuroinflammation, braked cytokines´ and chemokines´ network, false activation of antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin, Demodex folliculorum and UV radiation [2]. Vascular changes imply an increased vascular reactivity. This active vasodialation arises as a result of many extrinsic and intrinsic causes (endorphines, bradykinin, substance P). Degenerative changes to dermal connective tissue arise as a result of the UV component of sun radiation, very likely also of the red band of the visible light [3]. Similar cases of rosacea within a family have been reported, and genetic predisposition to the disease has been suggested [4]. Triggering factors are very important. They are not causing, but worsening symptoms of rosacea. To them belong: UV radiation, hot climate, hot baths, emotional stress, piquant, spicy and hot meals and hot drinks, cosmetics containing fluorides, fluorinated toothpastes, food high in histamine. Also physical activities connected with sweating, pressure, rubbing, hot bath and sauna, some medicaments (e.g. nicotinates, vasodilatation causing and some antihypertensive medicines, steroids, some biologics) and cosmetics containing alcohol, acetone, sorbic acid as well as abrasive and peeling preparations belong to triggering factors [5].

Based on specific clinical signs and symptoms, in April 2002, an expert committee assembled by the National Rosacea Society explicitly defined rosacea and classified it into the following subtypes: erythematoteleangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous and ocular. Besides, only one variant, a granulomatous one, was added [1]. Granulomatous (lupoid) rosacea was originally described in 1917 by Lewandowsky as rosacea-like tuberculid [6]. In 1949, Snapp concluded that the disease described by Lewandowsky was in no way related to tuberculosis, neither to a strongly reactive Mantoux’ test [7]. In 1958, van Ketel reported a group of patients with the typical clinical picture of rosacea, moreover presenting granulomas on histopathological examination [8]. Nevertheless, only in 1970 did Mullanax and Kierland call attention to a distinct form of rosacea that was characterized by papules on both medial and lateral facial areas and histologically by noncaseating epithelioid cell granulomas. They noticed that antituberculous therapy is not indicated in these cases [9]. Jansen and his group view lupoid rosacea, granulomatous rosacea, the rosacea-like tuberculid of Lewandowsky and lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei as identical expressions of rosacea and prefer the term “lupoid rosacea” [5]. Because at lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei always an extensive necrosis of collagen tissue in the centre of graluloma is present, while at GR rosacea there are small granulomas, we suggest they are not one identical illness. Clinically, with GR - except typical signs of rosacea - there are disseminated brownish-red papules or small nodules affecting the face, most often eyelids, above yokebones and perioral regions [5]. Extrafacial lesions occurring in 15 per cent of patients were presented by Helm [7]. Diascopy reveals lupoid yellow-brown infiltrate [5, 9]. The course of the disease is chronic. Histopathologically, perifollicular and perivascular noncaseating epitheloid granulomas with lymphocytes and plasmatic cells are present [1]. A dash can be comprised of giant multinuclear cells of the Langhans type and also of the foreign-body type [5]. As for the pathogenesis of lupoid rosacea, many factors are discussed (see above). Germs (mycobacteria) were excluded as causative agents [10]. Demodex folliculorum mites may play a role in this condition [11]. The diagnosis of GR is often disregarded [5]. A series of confusing differential diagnosis issues are raised. Steroid rosacea can be identical, but is supposed to improve when treatment is stopped. Sarcoidosis can be excluded by histological examination (sarcoid granulomas) and general evaluation. Lupoid perioral dermatitis [5, 12] can be very similar clinically and can have an identical histopathological examination, for their recognition mostly perioral handicap can be helpful, besides, some possible causative factors are usually found.

In the therapy, many ways of treatment are used. In the local therapy, many preparations were proven: adapalene, azelaic acid, benzoylperoxide, clindamycin, erythromycin, metronidazole, permethrine, pimecrolimus, retinaldehyd, tacrolimus, brimonidin, ivermectin and oxymethazoline [13, 14]. In the systemic treatment, only oral tetracyclines (in an antiinflammatory dosis) are officially allowed [15]. Peroral isotretinoin is used very often, its effect was documented in placebo checking studies. Modulating impact on kalicrein activity, expression of metalloproteases in keratinocytes, a profile of cathelicidin peptide, expression of toll-like-receptor 2, proliferation of lymphocytes and antioxidative, antiangiogenetic and antifibrotic effects were introduced as acting mechanisms [16]. Despite this, a working mechanism has not been satisfactory clarified till now and it has to be envisaged first of all as an anti-inflammatory one. A classically used dosage is 0,3 mg/ kg/ day, but every dose can be adjusted as required. With isotretinoin treatment, it is necessary to follow general recommendations (interactions, contraindications, labor controls etc). Though using this medicament with GR is off-label-use therapy, it has a steady place in clinical praxis in this difficult to treat illness. Jansen prefers to combine isotretinoin treatment with an oral dose of corticosteroids of 0.5-1.0 mg/ kg body weight daily for approximately ten to fourteen days [5]. For other alternatives (zincsulfat, metronidazole, dapson, minocyclin), there are only single casuistics till now. Combined treatment with peroral lymecyclin and topical metronidazol with good results was described [17]. It is necessary to avoid the triggering factors of rosacea.

The above described case of the 58-year-old man treated at our Acne Clinic is an example of beginning GR: reddish papules developed on the face of a middle-aged man of the Celtic type with no previous history of acne or rosacea. Its appearance was not characteristic at the beginning; erythema of the skin was not present. During next two months a slight erythema and teleangiectasias on the nose and cheeks appeared. There is a question whether the local application of the corticosteroid cream did not accelerate the development of the disease. The biopsy examination confirmed the diagnosis of GR. A therapy with peroral isotretinoin was started in a recommended dose of 0,3 mg/ kg/ day. A retinoid therapy was practised in accordance with all recommendations. No side effects of the therapy were found and an excellent result was achieved. The patient is undergoing a maintenance therapy (local therapy and avoiding triggering factors of rosacea) to prevent an exacerbation of the skin problems.

4.Concusion

A case of a middle-aged man with the diagnosis of granulomatous rosacea treated with peroral isotretinoin that brought an excellent result is presented in this case report. GR is a rather rare but distressing disease. All clinicians should have knowledge about the wide clinical spectrum of rosacea and about the possibility of treating it by specialists. All dermatovenerologists should consider the diagnosis of GR rosacea in patients with suspicious signs. A histopathological examination should confirm the diagnosis so that effective treatment can be started in time.

References

- Wilkin J., Dahl M., Detmar M. et al., Standard classification of rosacea, Report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea, J Am Acad Dermatol. 46 (4), 2002, pp. 584-587.

- Schauber J., Horney B. Steinhoff M., Aktuelles Verständnis Der Pathophysiologie der Rosacea, Hautarzt. 64, 2013, pp. 481-488.

- Fimmel S., Abdel-Naser M. B., Kutzner H., Kligman A., Zoubolis C.C., New aspects of the pathogenesis of rosacea, Drug Discovery Today. 5. 2008, pp. e103-e111.

- Jansen T. Rosacea. In: Plewig G., Kligman A. Acne and Rosacea, 3rd ed, eds: Berlin: Springer. 2000, pp. 456-501.

- Abram K., Silm H., Maaroos H. I., Oona M., Risk factors associated with rosacea, J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 24, 2010, pp. 565-571.

- Lewandowsky F., Über Rosacea-ähnliche Tuberkulide des Gesichtes, Corr Bl Schweitz Ärtze. 47, 1917, pp. 1280-1282.

- Helm K. F., Menz J., Gibson L. E., Dicken CH., A clinical and histopathologic study of granulomatous rosacea, J Am Acad Dermatol. 25, 1991, pp. 1038-1043.

- Van Ketel W. G., Does the rosacea-like tuberkulid exist?, Arch Dermatol. 79, 1959, pp. 723.

- Mullanax M. G., Kierland R. R., Granulomatous Rosacea, Arch Dermatol. 10, 1970, pp. 206-211.

- Lehman P. M., Rosacea: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Presentation and Treatment, Dtsch Arztebl. 104, 2007, pp. A1741-A1746.

- Grunwald M. H., Avinoach I., Halevy S., Granulomatous rosacea associated with Demodex folliculorum, Int J Dermatol. 31, 1992, pp. 718-719.

- Plewig G. Lupoid rosacea. In: Braun-Falco O., Plewig G., Wolff H. H., Burgdorf W. H.C. Dermatology, 3rd ed, eds: Springer-Verlag Berlin-Heidelberg-New York. 2009, p. 1011.

- Schȍfer H., Topische Therapie der Rosacea, Hautarzt. 64, 2013, pp. 494-499.

- Fallen R. S., Gooderham M. Rosacea: up-date on management and emerging therapies, Skin Therapy Left. 17, 2012, pp. 1-4.

- Vanstreels L., Megahed N., Lupoide Rosazea als Sonderform der Rosazea, Hautarzt. 64, 2013, pp. 886-888

- Thielitz A., Gollnick H., Rosazea, Systemische Therapie mit Retinoiden. Hautarzt. 62, 2011, pp. 820-827.

- Neto P. B. T., Lima J. B., Silva A. C. O., Rocha K. B. F., Nunes J. C. S., Granulomatous rosacea: case report- a therapeutic focus, An Bras Dermatol. 81, 2006, pp. S320-S323.