Information

Journal Policies

HIV-Positive Men Involvement in Pregnancy Care and Infant Feeding of HIV-Positive Mothers in Rural Maputo Province, Mozambique

Carlos Eduardo Cuinhane1,Kristien Roelens2,Christophe Vanroelen3,Gily Coene4

2.Department of Sociology, Eduardo Mondlane University, Maputo, Mozambique.

3.Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiteit Gent (Ghent University), Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium.

4.Department of Sociology,VrijeUniversiteit Brussel (Brussels University), Brussels, Belgium.

5.Department of Philosophy and Ethics, VrijeUniversiteit Brussel (Brussels University), RHEA – Research Centre Gender, Diversity and Intersectionality, Brussels, Belgium.

Copyright : © 2017 . This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction: Male involvement has been considered crucial to prevent passing HIV from mother to infant in sub-Saharan Africa. However, little is known about how HIV-positive Mozambican men and their female partners perceive and involve themselves in pregnancy and breastfeeding. This study analyses HIV-positive men’s role on compliance of medical advice recommended to prevent passing HIV from mother to infant.

Material and method: A qualitative study was carried out consisting of in-depth interviews with HIV-positive men and women, focus group discussions, plus semi-structured interviews with nurses and community health workers.

Results: HIV-positive men provided food and money for transport for their wives during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Some men encouraged their wives to attend antenatal care visits. However, most men did not accompany their wives to antenatal care, childbirth or postnatal visits due to work obligations and perceived stigmatisation in the community. Also, most men perceived a maternal clinic as a place for women. HIV-positive men supported adherence to antiretroviral therapy for their wives and infants, and they complied with prescriptions regarding antiretroviral therapy for themselves. Nonetheless, they did not often allow their wives to use contraception.

Conclusion: Some HIV-positive men supported women to follow some medical advice to prevent transmitting HIV from mother to infant.

breastfeeding, HIV-positive men, HIV-positive women, Mozambique, pregnancy ,AIDS

1. Introduction

Male involvement has been considered crucial to prevent passing HIV from mother to infant in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. In Mozambique, the Ministry of Health recommends all couples with unknown HIV status to do an HIV test before pregnancy. Men who are found HIV-positive are referred to initiate antiretroviral therapy and are advised to use condoms from then on. They are also requested to share their reproductive decisions with healthcare providers, and receive safe medical advice on conception and prevention of HIV [2].

Moreover, all men are invited to accompany their pregnant wives to the antenatal care, where they are both HIV-tested. Additionally, after childbirth, men coupled with HIV-positive women are advised to support their wives inpracticing exclusive breastfeeding and adhere to antiretroviral therapy for their infants. These precautions help to avoid re-infection among HIV-positive couples [3] and prevent passing HIV from mother to infant [4].

The literature further reveals men are important decision-makers regarding childbearing, women’s health and child care in sub-Saharan Africa [5-12]. They influence women’s decisions to become pregnant [5,6], to initiate and continue antenatal care [7,8] and to choose a place to give birth [9]. They also have influence over exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding [10,11]. Men are also decision-makers regarding the use of contraception and condom use[12]. It is also believed men have the power and economic resources required to encourage women to fully participate in maternal and child health and to engage in the enhancement of their health.

Male involvement has also been found to help HIV-positive mothers to comply with antiretroviral therapy and prevent passing on HIV to their infants [13,14]. Moreover, men can also benefit from early diagnosis, counselling and treatment if they are found HIV-positive[6].

Lack of male involvement has been considered a barrier to the enhancement of sexual and reproductive health for women. Studies [13,15] have shown when women were HIV-tested in antenatal care; they were not likely to disclose their HIV-status to their partners because they feared accusations of infertility, abandonment, discrimination, violence, and stigma.

Despite possessing the role of decision-maker around sexual and reproductive health, the involvement of men in maternal and women’s health issued is considered low in sub-Saharan Africa [6,16]. It is estimated male participation in HIV-testing and counselling during their partner’s pregnancy varies from 5% to 33%. As a matter of fact, the majority of studies report less than one in five men are actively involved .Moreover, men rarely participate in feeding the infants [17].

Several factors affect male involvement in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. These include cultural influences, such as considering reproductive health as a women’s domain and not a man’s responsibility [1,18].As well, there is a high tendency for men to resist HIV testing . Socio-economic factors such as lack of time to attend antenatal care [19] and the cost of travelling to the hospital[20] are viewed as barriers to strong male involvement.

Healthcare system-related factors also play a role in stopping men from being more involved. These include long waiting times at antenatal care clinics, mistreatment of spouses by healthcare workers[21] and the lack of adequate space for men at antenatal care clinics[15]. Moreover, lack of information, poor communication, stigma and lack of confidentiality [22] have been documented as barriers to male participation in preventing HIV infection of infants.

Dominant social norms with regard to masculinity also influence low male involvement in their health and maternal women’s health [23-25]. It is expected that a “real” man should have the ability to take risks and be self-reliant[23]. At all costs, men must avoid feminine behaviours and characteristics. Men must have the capacity to control their emotions, have power over women and embrace violence [23, 24]. All these social expectations affect men’s health seeking behaviour, thus they promote and sustain health risks among men [25].

Although plentiful has been documented about male involvement in women’s health, there is still a paucity of studies concerning HIV-positive men’s role in compliance to medical advice during pregnancy, childbirth and infant feeding. We do not know yet when and how HIV-positive men support their wives, and how do they engage in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. This research, therefore, analyses the role of HIV-positive men and their compliance to medical advice recommended to prevent passing HIV from mother to infant during pregnancy care, childbirth and infant feeding in Mozambique’s rural Maputo province.

In order to better understand men’s role during pregnancy, childbirth and breast feeding, we use the theory of practice as underlined by Pierre Bourdieu [26]. This theory offers an explanation of how both structural and individual factors may influence men’s involvement in maternal and child health within a specific context. Bourdieu [27] argues that people’s practices are derived from cultural perceptions of various local communities. Female and male roles are prescribed, and a certain sexual division of labour is defined within these communities. Men and women then conceive their patterns of perception based on their experiences within their communities and act according to their social role and the place they occupy within the society.

From Bourdieu’s theory, we can account that men’s involvement in women’s health and child rearing may also be influenced by the role they are assigned in the family and society. Understanding men’s roles during pregnancy, childbirth and infant feeding could contribute to improved prevention practices against HIV infection among infants, and improve HIV-positive women’s health.

2. Materials And Methods

We used a qualitative, explorative approach. The research took place in Namaacha and Manhiça– both rural districts of Maputo province, located in the south of Mozambique. In 2015, the population of Namaacha district was 51,257 [28] and approximately 263,736 people lived in Manhiça district [28].

These investigation sites were relevant for this study because Maputo province has the second highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the country. It accounts for 19,8% of HIV-positive people between the ages of 15 and 59 years. Roughly 20% are HIV-positive women while 19,5% are HIV-positive men [29].

Both districts are characterised by extended nuclear families. Families are mostly monogamous, but there are some polygamous families – men married with more than one woman [30]. They are patrilineal which means an individual family’s membership derives from and is recorded through his or her father’s lineage. Inheritance of property, names, rights, or titles passes through male kinship. Under local customs, only men have rights to inheritance [31]. When a man is married, his wife moves to her husband’s family and the couple resides with or near the husband’s parents [30].

In terms of sexual division of labour, men are assigned external activities of the household, such as paid work, cattle breeding, hunting and fishing. Women are essentially housewives. They reproduce, take care of the children [30, 32], fetch water, firewood, cook and work in agriculture [30]. However, more recently, there have been some social changes. Some women now also look for and engage in paid work [32].

Under local customs men are generally expected to provide security and food for the family. Husbands are considered to be the head of the family, guardian of the children and governor of the marital relationship [30]. Nevertheless, there are some female headed households, where women provide for the maintenance of their families [32].

Recruitment and interviews of study participants took place in six communities between January and March 2016. Three communities were purposively selected in each district. One was located at the centre of the district and two in neighbouring areas. The centre of the district is relatively urbanised, while the outlying areas have more rural characteristics. These differences were taken into account for analysis purposes.

Participants consisted of a purposely selected sample of 12 HIV-positive married men – 7 men in Manhiça district and 5 in Namaacha district. Twenty-four married women living with HIV were also chosen – 11 were selected in Manhiça and 13 in Namaacha. These participants were especially important in accessing information about the role men took during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding.

To select participants, the researcher approached local community based organisations working with people living with HIV. We visited the households of couples living with HIV between two and three times to establish trust with the participants. We then purposely selected the participants and those who agreed to participate were interviewed. Participants chose the date, time and place for the interview. A total of 36 in-depth interviews (12 HIV-positive men and 24 HIV-positive women) were performed until saturation was achieved.

The study also included 10 focus group discussions (FGD) – 4 in Manhiça district (three with women and one with the men) and 6 in Namaacha district (3 with women and 3 with men) – all of whom were HIV-positive. Each focus group discussion among men had 4 participants, while each focus group discussion with women had between 5 and 11 participants. A total of 59 participants were included in the focus group discussions, out of which were 16 men and 43 women.

A sample of 4 members in each focus group discussion was the minimal number required when doing research with hard-to-find people [33]. We decided to do focus group discussions with this limited number of participants due to the sensitive topic discussed and the characteristics of the participants. Only HIV-positive men with infants aged between zero and 2 years were included. Though the invitation was addressed to between 8 and 12 participants only 4came forward and participated in the focus group discussions.

To access participants for focus group discussions, we visited households with people living with HIV and we requested their input to discuss child’s health in the community. Participants chose the place and the time for these meetings.

We also conducted 6 semi-structured interviews with maternal and child health nurses working on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV program. One nurse was interviewed in each healthcare facility located in the community. We also interviewed 6 community health workers.

Both individual in-depth interviews and focus group discussions were conducted in Portuguese – the national language – for those who could read and write it. Tsonga, the local vernacular language, was used for those who could not understand Portuguese. All interviews and focus group discussion were recorded and then transcribed.

This study obtained ethical clearance from the Faculty of Medicine of Eduardo Mondlane University and Maputo Central Hospital Bioethics committee, protocol number CIBS FM & HCM /73/2014. Verbal information about the objective of the study was provided, and a written consent was presented to each participant to make an informed choice on whether or not to participate in the study.

All participants read and signed the informed consent forms. Those who could not read and sign chose someone in their trust to translate the information into the local language and to sign on their behalf.

A thematic analysis involving six stages was applied to obtain key themes emerging from the data. First, interviews were transcribed and then translated from Portuguese to English. Second, each transcription was read more than once and initial codes were generated. Third, the codes were used to identify and search various themes across the data. A theme is a set of words which captures something important about the data and represents some level of patterned meaning within the dataset. Fourth, the identified themes were revised and refined according to the research objectives. The final themes and subthemes were then defined in the fifth stage and presented in the result section. The sixth stage consisted of producing a report of these research outcomes.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the study and discussion. The first sub-section highlights the results of the study. These comprise demographic characteristic of the study’s participants and the main themes and subthemes emerging from participants narratives. The second sub-section presents the findings of the study.

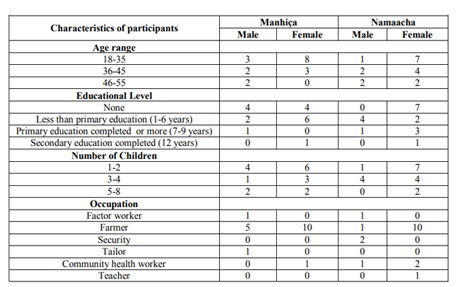

Most participants were between 18 and 45 years old, married or living with a partner. A considerable number of participants were farmers and had more than one child. Some participants lacked formal education (Table 1).

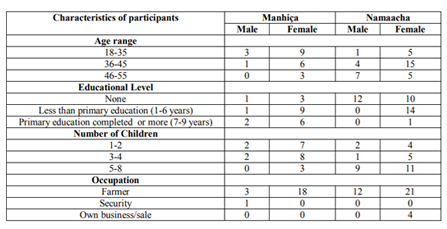

Focus group discussion participants were between 18 and 55 years old. All were married and the majority were farmers. About a half of the participants lacked formal education (Table 2).

The findings are ordered in five main themes: perceptions of pregnancy among HIV-positive men and women; the role of HIV-positive men on pregnancy decision-making; the role of HIV-positive men during pregnancy, childbirth and infant feeding; the role of HIV-positive men on HIV disclosure and adherence to antiretroviral therapy; and the role of HIV-positive men on contraceptive use. Analysis of these themes provided information about how men influenced the compliance of medical advice during pregnancy care, childbirth and infant feeding.

Participants held mixed perceptions. Among men, pregnancy was perceived as a normal event. This meant a woman had fully matured into an adult and has fulfilled the task of a married woman, thus securing her place in the family. For these participants, when a woman did not have children she was not yet grown up and she could leave the house whenever she wanted. One of the men explained this way When a woman is pregnant, [it] means that she has grown up. She may be grown up in terms of age, but that is not the case. Growing up means to show the reason why she was married and she came in my house. It means to become pregnant, bear children and expand the family. Among many men like me, when a woman is pregnant means that I get a new status – I become a father – and she becomes responsible of taking care of the children. If a woman does not bear children, she may even leave my house today because there is nothing that ties her here. That is, she has not children with me (…). Yes, there is disease [HIV] and we live with it, but it is a task of a woman to bear children. (41 years old man).

Women also perceived pregnancy as normal event. Different from the men’s definition, it meant growth, responsibility, fulfilment of women’s role and entitlement to respect; as one woman put it: When a woman is pregnant she shows that she has grown up and she is worthy of respect because she got pregnant from a man whose she is married to (…). To become pregnant means to fulfil the task that God has determined to us: that we should multiply and fill the earth. (38 years old woman).

HIV-positive men and women perceived pregnancy as a gift from God or an honour. Both said pregnancy was a gift of God because when they married they did not know if they would have children or not. A woman might take long time to get pregnant after marriage. Thus, when she does become pregnant, it demonstrates God has answered her prayers and she has shown her value. A man explained as it follows:

Pregnancy shows the value of a woman. A woman should not be afraid when she is pregnant because we exist to reproduce ourselves. There is no reason for a woman to be frightened due to pregnancy. It is the right of everybody. Becoming pregnant is a gift of God. When a woman is pregnant it is a responsibility for everybody who lives with her. Everything should be made to take care of this pregnancy. (45 years old man, FGD).

Both HIV-positive men and women said pregnancy was an honour and assigned new social status to the couple. After childbirth, a woman becomes a mother and a man becomes a father. One of the men said:

Pregnancy is an honour because a woman will become a mother. It is an honour for the mother and the father of the child. People can laugh at women who bear many children, but when a woman is pregnant must be respected because she expands the family. (48 years old man, FGD).

However, some men and women perceived a pregnancy as an illness. To them, pregnancy represented a risk of illness since a woman could be sick throughout or she might bear a baby infected with HIV. Moreover, a pregnant woman cannot do heavy work.She has to take care of herself.She is no longer “normal”. Others said a pregnant woman created anxiety as they did not know what would happen before childbirth. One man explained it in this way:

When a woman is pregnant, a man sometimes thinks she is sick. Myself, for example, when my wife is pregnant I think she is sick. I think I have given her an illness because you expect many things. You do not know if she will carry the pregnancy until to the end, and whether she will bear a healthy baby. Thus, she is sick. I only become happy after childbirth because I can see now she has a baby. (30 years old man, FGD).

This perception was mostly among men whose wives experienced a risk pregnancy or women who were ill throughout their pregnancy. They said pregnancy becomes an illness if the mother is sick throughout or when she failed to follow antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy.

All men and women said living with HIV did not prevent them from having more children. Children were perceived as a blessing, an honour for both women and men. Both said children enhanced the social status of a couple and maintained the family name. After the baby was born their names were substituted by the names of their children. Thus, the community called them “mother of” or “father of”– plus the name of the children. One man said:

Children mean continuity of the family. My surname will not disappear because is attached to my children. Besides, when people are looking for me they say: father of…That puts me high. Many people might not know your own name, but the name of your children. They always refer to me and my house from my children’s name (…) It is a great responsibility and honour to the father. (51 years old man, FGD).

Women said they would not be worthy of respect unless they had children. They also said men were respected and gained prestige when they have children. There was a consensus that remaining childless would always lead to conflict among couples and with the husband’s family. Some women said their husbands impregnated other women because they could not get pregnant. One woman narrated the following:

My husband impregnated another woman 3 years after living together. I could not get pregnant and he had not children before. He just came and told me he had another woman because I could not give him a child. We argued because he accused me of not giving children while he also had not children before. He told me to leave the house, but I did not accept. I got pregnant a few months later after I had taken traditional remedies. (22 years old woman).

As well, some men said a man without children would not have the same value as those who have children. Moreover, men also perceived a woman who did not bear children as a “man”. For these men, a relationship was only fulfilled when a woman became pregnant. One man explained it in this way:

When I am married, I expect my wife to become pregnant. If she does not get pregnant, I think we are still two men in the house. If she does not get pregnant, I get desperate. I look for treatment in witchdoctors, health providers at healthcare facility and churches to ensure she gets pregnant (…). If I have a wife, life is like that, she must end up getting pregnant (…).(45 years old man, FGD).

All men and women knew their HIV-positive status prior to their lastborn child. However, they did not plan the pregnancy and they did not share their intention of pregnancy with a healthcare provider.

Some women did not plan their pregnancies because they did not want to get pregnant. Nonetheless, they were not using contraceptives and their husbands were not using condoms. Others said they stopped contraceptive use due to side effects. However, men expected their wives to get pregnant any time after the infant completed the age of two years. They said this was the recommended time stated by healthcare providers. They also said they allowed their wives to use contraceptives before the baby was two years of age.

The decision on pregnancy sometimes was reached by both partners together. For others, only the husband made the decision. However, sometimes, the decision for pregnancy did not follow the recommendations of healthcare providers. Some women got pregnant before the infant reached the recommended age of 2 years.

None of the men or women sought out a healthcare provider before pregnancy. Some did not know while others said there was no need because they were following antiretroviral therapy. Women said the intention of becoming pregnant was a secret of the couple and it was not possible to share it with healthcare providers. Other women said their husbands did not accept and did not allow them to seek out a healthcare provider before pregnancy. One woman recalled her experience and explained as it follows:

I got the second pregnancy soon after breastfeeding cessation. This was when I went to visit my husband in South Africa – where he was working. He told me he wanted the second baby. When I told him that we had to seek out medical advice, he said he could not wait and he had no time. He threw away my pills for contraception and he said the healthcare providers would do what they wanted to do to me after pregnancy. (22 years old woman).

All HIV-positive men perceived treatment was only possible after a woman was pregnant. They did not know why they had to share their intention of impregnating their wives with a healthcare provider. Others said a woman was the only responsible to seek out healthcare providers as she knew when she could or could not get pregnant. One man explained it this way:

It is almost impossible for men to seek out healthcare providers because women are the only ones that know when to get pregnant. A woman sees menstruation and she may decide not to get pregnant. If she wants, she can go to the healthcare facility to get pills to prevent pregnancy. I think it is very tricky to share pregnancy intentions with a healthcare provider because the wife is mine and not the healthcare provider’s. By the time she gets pregnant I have forgotten the healthcare provider (…). A woman should seek out the healthcare provider when she is pregnant (…). This does not make sense to share pregnancy intention with the healthcare providers. He can say I want your wife to come alone next week, and you do not know what he will do to your wife. (41 years old man, FGD).

Men perceived that it was acceptable to seek out a healthcare provider or a witchdoctor when their wives or they had problems in bearing an infant; otherwise there was no need. However, some men whose wives had problems to getting pregnant sought the services of a witchdoctor and took traditional remedies rather than finding a healthcare provider. Only a few men perceived the need to get the advice of a healthcare provider when a couple did not yet have children. One man explained like this: (…) I know my wife and I are living with HIV. If I want more children, I know we must seek out a healthcare provider and not a witchdoctor. A healthcare provider answers any doubt, he advises me when to plan my children, when to stop using condom and impregnate my wife. He does check out us and he tells me when my wife can get pregnant (…). If I go to a witchdoctor, he will give traditional remedies that will give me diarrhoea. (48 years old man, FGD).

3.1.4.1. HIV-Positive Men’s Perceptions of Pregnancy Care and Childbirth

HIV-positive men perceived pregnancy care as a woman’s responsibility. They said women knew better what should be done during pregnancy than them. They viewed their responsibility for helping pregnant women as only when they needed it. In their estimation, such needs included accompanying their wives to the healthcare facility, when they were sick, during childbirth, providing food to the family, and money for transport.

Women, however, perceived pregnancy care as a shared responsibility of the couple. They said women do not become pregnant alone. Men were viewed as responsible for the pregnancy, and therefore their main task was to ensure its care and safety.

They said men should accompany a pregnant woman to antenatal care visits, attend childbirth, and do “heavy” housework when a pregnant woman was no longer able to do it. Heavy housework included fetching water, firewood, pounding, bathing children and cooking. Moreover, women said men should provide food for the family.

3.1.4.2. HIV-Positive Men’s Perceptions on Antenatal Care

All HIV-positive men perceived that a pregnant woman should go to an antenatal care and all subsequent antenatal visits throughout pregnancy. However, antenatal care service was considered to be a women’s service. They said men benefited from this service indirectly since nurses provided diagnosis for the mother and monitored the development of the foetus.

However, men said the antenatal service helped women to have safe childbirth at the healthcare facility and prevented infection of HIV to the baby. Nonetheless, all men said the antenatal service was not directly beneficial to them.

There were mixed perceptions about the timing of the first antenatal visit. Some men said a pregnant woman should go to the first antenatal care during the third month, unless she was unwell. They said the first and second months were too early and the women were not yet sure if they actually were pregnant. Others said pregnant women should have their first antenatal visit at the sixth month. By doing so, the number of trips to the clinic would be reduced. Some men maintained fewer visits for antenatal care would prevent expectant mothers from getting tired of having to travel. This is how one man explained it: Women should go to the first antenatal care at sixth month, unless she is sick. This prevents her to get tired to go to the health facility every month. But if she goes at sixth, it would be missing three months only (…). She has to follow nurses’ advices and she has to go to the next antenatal visits. She cannot miss it. If she missed it she would get trouble with nurses during childbirth. Nurses would say she did not have a good childbirth because she missed antenatal care. So, to prevent this trouble, it is better to follow all subsequent antenatal care visits. (55 years old man).

Although all men said pregnant women should go to antenatal care, some said pregnant women should also seek a church pastor who would pray for them throughout pregnancy and prior to childbirth. Many men believed the pastor’s prayers would help to prevent evil spirits who could cause trouble for pregnant women and during childbirth.

Women also shared some male perceptions on the timing of antenatal care. They said a pregnant woman should go to the antenatal care at third month, unless she was sick. They agreed at three months a woman can be sure she is pregnant. Only then was it acceptable to inform their husbands. Before this time, they could get into trouble with their husbands if they later suffered a miscarriage. However, some women did go to their first antenatal visit at the fifth or sixth month. Generally, this was due to lack of money for transport. As well, just as the men suggested, some women did seek their pastor’s prayers during pregnancy and before childbirth.

3.1.4.3. HIV-positive men’s practices during pregnancy care and childbirth

HIV-positive men’s practices and experiences during pregnancy care and childbirth were quite varied. Some men advised their wives to go to their first antenatal care visit as soon as they knew she was pregnant. These husbands reminded their wives to follow up with antenatal care visits and kept up to date about the results of the antenatal visits. They wanted to know about the development of the foetus as well as the nurses’ recommendations. One man explained his role this way: Whenever she went to antenatal care, I often asked her what nurses had said about the foetus and what she should do to take care of the pregnancy. I always reminded her[about] the next antenatal care visit to prevent she does not miss antenatal visit. (42 years old man).

However, most men did not accompany their wives to antenatal visits. Rather, they accompanied their wives when they perceived it was a time to give birth. Men said childbirth signs always started at night and they had to accompany their wives to the healthcare facility. However, if their mothers or mothers-in-law were available to accompany the pregnant woman to the healthcare facility, they would rather stay away.

Few men considered accompanying their wives to the healthcare facility during pregnancy as a man’s responsibility. They perceived their pregnant wife as a sick woman. They said a pregnant woman was at risk. Therefore, they accompanied them to ensure they were safe. One man explained it in the following way: It is our responsibility to accompany our wives to healthcare facility when they are pregnant. When a woman is pregnant is like when she is sick. She is at risk and she cannot go to healthcare facility alone, unless her husband is busy or working. I always accompany my wife to the healthcare facility when she is pregnant or sick. As well, it is my right to accompany my daughter when she is sick (…). I do not like to let my wife go to the health facility alone, unless I am working because I do not know whether she will arrive safe or not. (45 years old man).

Men who ever accompanied their wives to the healthcare facility during pregnancy were not involved in antenatal care visits. All said they had never been invited to enter into the antenatal care room with their wives. Some men perceived the antenatal care service was only for women and forbidden to men. Moreover, others only accompanied their wives to the healthcare facility, but did not enter it or wait inside.

Almost all men provided their family with food and money to transport the wife to the healthcare facility. Many prepared for childbirth by saving money for transport to take the pregnant women to the healthcare facility or to buy new clothes of the baby. Some men said their customs did not allow them to buy clothes for the baby before childbirth, as one man explained: I used to save money to buy the clothes of the baby after childbirth and for transport to take her to the healthcare facility during childbirth. Our norm does not allow to buy clothes in advance for the baby who is still in the belly as we did not know whether she or he was going to be born. (42 years old man).

Nevertheless, few men did housework such as fetching water, firewood, pounding and cooking even when their wives were between eight and nine months pregnant. This was particularly the case when there was no sister, sister-in-law or the mother to help their wives. Men engaged in housework when they perceived the pregnancy was “big” and their wives were not able to do “heavy housework”.

Most women said their husbands never accompanied them to the healthcare facility during pregnancy. Some women said their husbands did not even advise them to go for antenatal care visits. They were not interested in nurses’ advice and advocated having the first antenatal care visit later in the pregnancy. And, some husbands did not provide money for transport. One woman recounted her story: My husband did not help me during pregnancy and child birth. He did not give me money for transport to go to the antenatal, though I told him I was pregnant when it was two months. Instead, I had to do some paid job to get money for transport. I went to the first antenatal visit at the 6th month

(…). I know I put my baby at risk of HIV infection, but there was not otherwise (…). I would had gone to the first antenatal visit at 3rd month if my husband had given me the money for transport.(35 years old woman).

Others said their husbands never accompanied them to the healthcare facility during childbirth, Sometimes, some husbands participated in childbirth at home but this was because they did not allow their wives to go to the healthcare facility when it was time to give birth. One woman explained it as follows: Birth signs started at afternoon. When I told my husband, he said it was not yet the time to go to the healthcare facility. He left me alone at home and he went to meet his friends around the neighbourhood. After some hours, I felt much pain and requested a child to call him, but he did not come home. When I felt I could not even walk, I called some of my aunts who live nearby. When they arrived, they helped me to give birth. We went to the healthcare facility after childbirth. (45 years old woman).

Nonetheless, a few women said their husbands accompanied them to the healthcare facility when it was time to give birth as it started at night. Others said their sisters-in-law, mothers or mothers-in-law took them to the healthcare facility just prior to childbirth, while their husbands remained at home.

Some women said their husbands provided food, gave money for transport, prepared for childbirth and were interested in nurse’s advice on pregnancy care. Nonetheless, most women said their husbands did not help with housework until they gave birth. Others said their husbands did not provide food, money for transport, did not prepare for childbirth, and did not help them with housework.

All women interviewed said they would like to be accompanied to the healthcare facility by their husbands. Moreover, they perceived male’s attendance to the antenatal visits as an opportunity for men to learn about pregnancy care, safe sex and how to prevent transmitting diseases to the couple and the baby.

Men perceived breastfeeding as a women’s task. Men’s responsibility was viewed as providing food for the family, buying clothes for the baby, supplying money for transport to postnatal visits and helping women with housework if other family members were not available. As well, some men said the women made the decision about the cessation of breast feeding and the introduction of complementary feeding while others reported it was a shared decision.

Women also perceived the breastfeeding process as their task. However, they said they would like more involvement from their husbands in housework for at least two weeks after childbirth, as they were still too weak to perform these activities. They also expected men to provide food, clothes for the baby and money for transport, as well as accompanying them on postnatal visits.

During the breastfeeding period, men said they did not accompany their wives to postnatal visits. However, they said they bought clothes for the baby, provided food for the family and for the baby – during the complementary feeding period. Additionally, some men said they did some housework since no one else was available to help their wives. Others claimed they cooked for themselves because their social norms did not allow a woman to cook for a man after childbirth. One man explained it this way:

My wife does not cook for me after childbirth. I cook myself. In our norm, a woman is considered impure after childbirth. She cannot cook for her husband. She is only allowed to cook for me after 33 days. That period is acceptable because she is back to normal. (55 years old man).

Men and women reported practicing mixed breastfeeding. They gave water and traditional remedies to the baby before six months. For those who could afford to buy it, formula was given to babies aged 3 or 4 months. All men and women said they introduced solid food between 4 and 5 months after birth. This was done because they believed a baby needed to be fed more than breast milk before reaching the age of six months.

All men reported facing many constraints not allowing them to accompany their wives to antenatal visits. Work was the most common reason. They also believed the maternal clinic was a place for women and children. Additionally, some men felt uncomfortable accompanying their wives as their communities disapproved this practice. They stated it was not common to see men escorting their wives to antenatal or postnatal visits, unless they were ill.

Men also perceived housework as a female activity. They would only help if their wives were sick and no family member or neighbour was available to help. A man who accompanied his wife to a healthcare facility or helped her with housework was perceived as being bewitched by his wife. One man explained it like this: When you frequently accompany your wife to the healthcare facility and you always help her with cooking, washing, fetching water or firewood, people – both men and women – start saying: “haaaa, that man is bottled” [bewitched]. People laugh at you (…). Even if I cook today, tomorrow and after tomorrow while my wife is not sick, they say I am a weak man. (45 years old man).

Some men suggested pregnant women should do all the housework until childbirth. Men said if they helped their wives during pregnancy and breastfeeding, the women would want them to do the housework everyday even after pregnancy and childbirth. Worse yet, they would tell their female friends about it. One man expressed his view like this: Pregnant women should do every housework until childbirth since our mothers and grandmothers also did the same. Some women are foolish. You help her today with the housework due to her situation [during pregnancy and after childbirth]. But after that she starts often forcing you to do it. When she meets her friends, she tells them: “that man is mine, he is stagnant; I even force him to wash the dishes” (…). Thus, to prevent this bad spirit is better to let her do the housework alone. My young neighbour fetches water every day while his wife is sleeping. He says his wife is pregnant. But that is not true. He is suffering because he once helped his wife. Now he often does it. (55 years old man).

Women also agreed men dealt with many constraints making it difficult to accompany their wives to antenatal and postnatal visits, or helping them with housework. They said men could not fully help because they had to work or look for a job. A few women stated some men did not accompany their wives to antenatal visits because they had extra-marital relations and had impregnated other women. They feared their spouses or the community at large would learn about their extra-marital misbehaviours.

Women reported men did not often do housework as they perceived it as feminine work. Some women believe men’s attitudes towards housework are learned when they are young, influenced by their family of origin. Others said if men did house work they would be afraid and they would be looked upon as bewitched by their wives.

3.1.7.1. The Role of HIV-Positive Men on HIV Testing and Disclosure of HIV Status

Most HIV-positive men only had an HIV-test after they had fallen ill and had not been previously tested. Some men had themselves HIV tested when they began new relationships. Some men went to clinics with their wives and both were HIV tested. Others were requested to come in for testing by healthcare providers after their wives were discovered to be HIV-positive.

Many men admitted they were fearful of HIV-testing, saying they were afraid they could lose their wives. If a man tested HIV-positive while the test result of his wife was HIV-negative, woman might abandon him. However, if a man was tested HIV-positive, people in the community would most often conclude he was infected by his wife. One man explained it: Men do not accept to go to the healthcare facility for HIV-test, unless they are very sick. They are afraid of what people may say when they get HIV-positive. Generally, people say: “look, a woman has killed her husband”. Thus, even when healthcare providers give an invitation latter to the women, men do not accept to go to the healthcare facility.(45 years old man).

HIV-disclosure is considered a challenging process. However, HIV-positive men did report their HIV status and urged their wives to have an HIV-test. They believed lack of disclosure could put their family at risk. One man narrated a case where he lost his baby because his wife was afraid to disclose her HIV-positive status.

I lost one of my children due to HIV/AIDS. The baby got sick and my wife never told me what he was suffering from. We spent a lot of money for treatment. But one day I decided to go to the healthcare facility with them. We all did HIV test and we were found HIV-positive. She said she knew during pregnancy but she was afraid to tell me. We followed the treatment but the baby died since it was too late. She became pregnant again, we followed antiretroviral therapy and the baby has grown up, and he is HIV-negative. (34 years old man, FGD).

Some men said the best way to prevent conflict among couples is to do HIV-test for both at the same time. They believed both men and women were afraid to disclose the results of their HIV-tests. One man described his experience in this way: If my wife is the first to know her HIV-positive status, she may be afraid to tell me about it because she thinks I will say that she got it in extra marriage relations. Myself too, I am afraid because she might say I engaged into sexual relations with someone else. She may even tell her friends that I have gone to get disease and I want to kill her. But, our case was good because she went to the healthcare facility and she came with an invitation letter. We then went together, we tested and we were both found HIV-positive at the same time. We were also advised that there was no way we could know who was infected first. (42 years old man).

Women perceived men had a responsibility to have the HIV-test first or invite their wives to do it together. They said many men still believe they were HIV-infected by their wives. These challenges the process of HIV disclosure, especially if a woman was tested HIV-positive. Moreover, women believe men should immediately go to healthcare clinics when they are requested to have an HIV-test. However, when most men receive such an invitation letter from healthcare providers, they generally ignore it.

Most women knew their HIV-positive status when they were HIV-tested at antenatal care. Some knew when they were sick and others when they engaged in a new relationship after a divorce. However, few women requested an HIV-test from a male partner prior to pregnancy in a new relationship.

Women said disclosing HIV-positive status was very difficult, unless their husbands also agreed to visit the healthcare facility to be tested together. They said men view HIV as a “women’s disease”. Most women said they only disclosed their HIV-status following their husbands’ agreement to go to the healthcare facility. Some women had hidden their HIV-positive status for up to two years others withheld this information until their husbands became sick and they went together for an HIV-test.

Some women had chosen not to disclose their HIV-positive status to their husbands because their husbands refused to go to the healthcare facility. This practice was most common among women living in polygamous marriages. Others said they would not disclose their HIV-positive status because their husbands frightened them; as one woman narrated: My husband cannot know that I am HIV-positive and I am taking antiretroviral drugs. He never accepted to go to the healthcare facility, though I gave him an invitation latter from the healthcare providers. He does not know his own HIV status. When I got sick he did not take me to healthcare facility. I went for treatment as I had tuberculosis. One day someone who live nearby told him that he saw me with antiretroviral drugs. My husband asked me about it but I denied. He said if he found me taking antiretroviral drugs he would kill me. One day he forced me to entre in the boat at night in one of the river nearby, and I suspected he wanted to kill me. I managed to run away. Since then I never got courage do disclose my HIV-positive status (…). He will know his own HIV status when he gets sick and go to the healthcare facility. (35 years old woman).

3.1.7.2. The Role of HIV-Positive Men in Adhering to Antiretroviral Therapy

All men said they commenced HIV treatment as soon as they were tested and diagnosed HIV-positive. They reported taking antiretroviral together with their wives. Some men said they had chosen to take antiretroviral drugs at the same time as their wives. Others said they went to the healthcare facility together to collect their antiretroviral medications. Men said when they were away from home due to work; their wives would send antiretroviral drugs to them each month.

Most men said they had never stopped HIV treatment because they knew if they did it, they would get sick and die. Most also reported they fully approved of HIV treatment to their infants. However, several spoke of some men in the community who had ended HIV treatment as they were ashamed to be seen taking antiretroviral drugs.

Women also said they followed HIV treatment since the time they were tested HIV-positive – during pregnancy and after the breastfeeding period. Some women took antiretroviral drugs together with their husbands, while other said they needed to remind their husbands to take medications as it seemed they had forgotten about it.

Some women said even when they were not pregnant they would bring antiretroviral drugs to their husbands who could not go to the healthcare facility due to work. Others reported sending antiretroviral drugs to their husbands who were working in South Africa.

However, some women said their husbands did not regularly take their antiretroviral drugs. This was common when men went out at night for parties and came back late at night or the following day. Others said they divorced their former husbands because they did not allow them to take antiretroviral drugs nor did they accept it for themselves, as one woman explained: I got pregnant and I did HIV-test. The nurses gave me an invitation letter. After my husband had read it he said that was my problem. He did not accept to go to the healthcare facility and did not allow me to take antiretroviral drugs. We started arguing and our relationship was not good anymore. I left him and I went back to my parent’s home. I continued HIV treatment. I gave birth and the baby is not HIV infected. I am still taking antiretroviral drugs (…). I take care of my life and my children (…). Actually, I meet my former husband at the HIV treatment clinic. He has decided to take antiretroviral drugs too. (31 years old woman, FGD).

Women also admitted they sometimes missed taking antiretroviral drugs once or twice per month. This most often occurred when they attended a family party or a night event. It was their understanding one could not take antiretroviral drugs two hours after the time he or she had regularly taken it.

Some women had ended HIV treatment in the past. They said they were tired of taking antiretroviral drugs. However, they resumed HIV treatment when they fell sick. Others stopped taking antiretroviral drugs when they married a new husband, after a divorce, or their previous husbands had died. They said it was difficult for them to disclose their HIV-positive status prior their husbands’ disclosure.

Other women who had not yet disclosed their HIV-status to their husbands said they still managed to take antiretroviral drugs. Some told their husbands the pills were for high blood pressure or tuberculosis. Yet others chose to take their antiretroviral drugs at a time when their husbands were usually not at home. One woman explained it this way:

My husband usually comes at home at 20 o’clock. He often arrives after I have taken my antiretroviral drugs. I have chosen to take it at 18 o’clock. Now it is easier because we take one pill per day (…). I never put antiretroviral drugs in my bedroom. I put in my children’s bedroom. He never enters there (…). I used to give the antiretroviral to the baby when he had left to work or early morning before he woke up. (35 years old woman).

Community health workers reported most people living with HIV – both men and women – ceased antiretroviral therapy for a variety of reasons. These included lack of food, side effects brought on by the antiretroviral drugs, fear of shaming by other people, and abuse of alcohol and smoking. This last reason was especially true among the men. Most men did not want to reduce their alcohol consumption but feared blood analysis results would reveal they were not complying with medical recommendations. Thus, they preferred to stop antiretroviral therapy and medical consultation.

Few men reported their wives were using contraceptives because they were still breastfeeding. They said their wives used injections and pills. Men said they allowed their wives to use contraceptives to prevent getting pregnant before the baby had grown out of infancy.

Some men said their wives were not using contraceptives and had many beliefs about them. They believed contraceptives could make their wives very fat; they prevented menstruation; or it reduced the potential number of times a man could engage in sexual intercourse with his wife. One man explained it like this: My wife does not use contraceptive. Injection or pills prevent her menstruation (…). You cannot easily tell she is pregnant or not. She might stay 3 months before she sees her menstruation while she is not pregnant. Besides, contraceptives reduce the potential number of times of sexual intercourse. A man can easily reduce his potential from four times to one time when his wife uses contraceptive (…). Women do not lubricate when they are using injections.(55 years old man).

Most men said they did not use condoms regularly. Condoms were used when their wives were pregnant but not when they resumed sexual intercourse during the breastfeeding period. Some men said they did not use condoms due to lack of pleasure, or they just didn’t like it. Some felt there was no need for condoms since both were already infected. Others said some women do not accept the use of condoms. One man explained it this way: Some women do not accept a condom. They say you cannot impregnate them using condom. Only women who aware of HIV and know HIV-positive status of the men accept condom. That is why HIV spreads because we, men, sometimes infect women and leave them suffering alone as we have our own wives (…). Somehow, we are the one who look for women. (45 years old man).

As well, there were women who did not use contraceptives regularly. Some said they had used injections or pills but only during the breastfeeding interval. The same scenario was reported by women who had decided they did not want more children. Others did not use contraceptives due to side infects and because their husbands never accepted them. Some women reported having menstruation for an entire month when they used pills. Women said men associated contraceptive use with infidelity. Moreover, women who do use contraceptives without the knowledge of their husbands, risk losing their relationships and homes.

Also, women reported their husbands did not use condoms regularly. Some said their husbands only used condoms during pregnancy because they had been told the baby would also be HIV infected. Moreover, they said they had no power to force men to use condoms. And, even when men were provided condoms at the healthcare facility, they would throw them away on their way home as they did not want to “eat an unpeeled banana”.

Women also recounted how some women did not want to use condoms because they wanted children or perceived the prophylactic might create problems such as skin irritation after sexual intercourse. One woman explained as follows: Sometimes women do not accept condom use because they want children. Others also fear to have irritation after sexual intercourse (…). But other women do not accept as they already know they are living with HIV and they do not care if a man gets infected. They say: “someone infected me, as we do not know our HIV-status, maybe, we are infecting each other”. (27 years old woman, FGD).

This study’s findings reveal the social role assigned to men in the community and how the family influences men’s perceptions and involvement in pregnancy decision-making, pregnancy care, childbirth, and infant feeding.

In these communities, men are assigned external activities of the household, while women were essentially housewives, bore offspring and then took care of the children [30,32]. This division of labour according to gender norms seems to have influenced men and women’s perceptions of men’s roles regarding maternal and child health. As our study’s results exhibited, men and women perceive the man’s role as breadwinner. Their culture expects men to provide security and food for the family throughout pregnancy and infant feeding.

Although men were considered to be the head of the family and guardian of the children [30], this study’s findings revealed men’s involvement in maternal and child health was marginal. Men perceived pregnancy decision-making and seeking out healthcare providers before pregnancy as women’s tasks. Nevertheless, they supported their wives to attend antenatal care, give birth at the healthcare facility and partake in postnatal visits.

HIV-positive men did not plan their wives most recent pregnancy and did not allow them to seek out a healthcare provider before pregnancy. Moreover, they did not look for a healthcare provider for themselves as they perceived they had no problem impregnating their wives. This suggests men do not know why finding a healthcare provider before pregnancy is important to them as well as their wives.

Though women perceived pregnancy care as a shared responsibility of the couple, men viewed it as a woman’s role. Most men did not accompany their wives to antenatal care, childbirth or postnatal visits. This is often due to men having to be at work but men also hold the perception that maternal clinics are places for women and children. Additionally, men do not want to be perceived as “bewitched” and therefore stigmatised in the community. Similar constraints have been documented in Kenya [7], Tanzania [34], Uganda [15], Ethiopia [35], South Africa[36] and other sub-Saharan countries [37,38].

Men who did accompany their wives would not enter the antenatal or postnatal room. This was because they believed the maternal clinic was not directly beneficial to them. This result is congruent with findings from Ethiopia [39], suggesting there is a missed opportunity to involve men in maternal and child health.

Men also perceived breast feeding as a woman’s domain. The same holds for housework, although women expected their husband’s help even if just a little. Men only assisted their wives with housework after childbirth. However, this was only due to an absence of family members to help their wives. Factors influencing men’s lack of involvement in household activities included pride, family education and perceived stigmatisation in the community. Men equated their involvement in housework with a loss of masculine power.

This perception is consistent with dominant masculinity norms [23,24]. HIV-positive men seem to feel the responsibility in caring and protecting their pregnant wives. However, their involvement aligns with socially structured gender norms [27]. Nonetheless, some HIV-positive men exhibiting some sensitivity are working to cast off the dominant masculinity norms. They accompany their wives to the healthcare facility and support them to comply with medical advice.

Moreover, HIV-positive men have played a pivotal role in HIV-testing, HIV disclosure and HIV treatment. This study’s findings show more men are disclosing their HIV-positive status to their wives. This may be linked to the fact they were HIV-tested when they were sick or when they were seeking out a new relationship. This seems to influence the couple’s adherence to HIV treatment.

All HIV-positive men supported their wives to use antiretroviral drugs throughout their pregnancies and after breastfeeding. These men also took antiretroviral drugs for themselves. They accepted antiretroviral drugs as the only means to maintain their health. Similar predictors to the adherence to antiretroviral therapy were also documented in Togo [40].

However, HIV-positive men did not often allow their wives to adhere to contraceptive use. They perceived it as a burden to their wives’ health and disruptive to sexual activities. Similar findings were also found in Nigeria [41] and Uganda [42]. As well, these men did not often adhere to condom use due to the idea that a condom reduces their pleasure. They also believed condom use was not necessary as the man and woman were already HIV-infected. Some also believed women did not like using condoms. Minimal condom use among people living with HIV was also documented in previous studies [43].

4. Limitation

Reports of men’s role on pregnancy decision, pregnancy care and childbirth were retrospective. Thus, recall-bias may have affected the consistency of participant’s narratives. The study is also subject to sample-bias in the two selected districts because it did not access other HIV-positive men and women who were not under jurisdiction of community-based organisations working with people living with HIV.

5. Conclusion

The study’s findings suggest some HIV-positive men are involved in maternal and child health. Currently, the man’s role is mainly that of breadwinner and provider for the needs of their wives and infants as prescribed in the sexual division of labour of their communities.

Moreover, they supported compliance with medical advice such as adherence to antiretroviral therapy for their wives, infants and themselves. They also promoted their wives to attend antenatal care visits throughout pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal follow-up. Therefore, some HIV-positive men contributed to the prevention of HIV from mothers to infants. Nonetheless, socially assigned roles of men did not enable them to be involved in maternal and child health as part of the process. Instead, they functioned as providers for the needs of the family.

This study proposes men must be more involved in pregnancy decision making, in following medical advice, in pregnancy care, in childbirth and with infant feeding through health education provided by the healthcare providers. Maternal clinics should also benefit men by disseminating education/advice on sexual and reproductive issues as well as associated risks.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by a project grant from the Desafio, Development Program in Reproductive Health; HIV/AIDS and Family Matters; Eduardo Mondlane University, Mozambique and Flemish Interuniversity Council (VLIR).

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Male involvement in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Geneva: WHO.(2012).

- Ministry of Health of Mozambique. Plano Nacional de Eliminação da Transmissão Vertical do HIV: 2012-2015. Maputo: Ministry of Health of Mozambique.(2011).

- Barreiro P., Castilla J.A., Labarga P. and Soriano V. Is natural conception a valid option for HIV-sero discordant couples? Human Reproduction; 22(9): 2353-2358.(2007).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). PMTCT strategic vision 2012-2015: preventing mother-to child transmission of HIV to research the UNGASS and Millennium Developing Goals. Geneva: WHO.(2010).

- Kroelinger C.D. and Oths K.S. Partner support and pregnancy wontedness. Birth; 27(2):112-119. (2000).

- Osoti A., Han H., Kiuthia H.H. and Farquhar C. Role of male partner in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Research and Reports in Neonatology; 4: 131-138. doi:102147/RRN.S46238.(2014).

- Kwambai T.K., Dellicour S., Desai M., Ameh C.A., Person B., Achieng F., Masin L., Laserson K.F., Kuile F.O.T. Perspective of men on antenatal and delivery care service utilisation in rural western Kenya: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth; 13:134. Doi: 10.1186/1417-2393-13-134.(2013).

- Mangeni J.M., Mwangi A., Mbugua S., Mukthar V. Male involvement in maternal care as determination of utilisation of skilled birth attendance in Kenya. USAID: Demographic and Health Survey; 93.(2013).

- Nyandieka L.N., Njeru M.K., Ng’ang’a Z., Echoka E. and Kombi Y. Men involvement in maternal health planning key to utilisation of skilled birth service in MalindiSubcounty Kenya. Advance in Public Health. doi:10.1155 /2016/5608198.(2016).

- Desclaux A. and Alfieri, C. Counselling and choosing between infant-feeding options: overall limits and local interpretations by health care providers and women living with HIV in resource-poor countries (Burkina Faso, Cambodia and Cameroon). Social sciences & Medicine. 69: 821-829. (2009).

- Mitchell-Box K.M. and Braun K.L. Impact of male-partner-focused on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity and continuation. Journal of Human Lactation; 29(4): 473-479.doi:10.1 177/0890334413491833. (2013).

- Stuart, G.S. Fourteen million women with limited options: HIV/AIDS and highly a. Effective reversible contraception in sub-Saharan Africa. Contraception. 80: 412 – b. 416.(2009).

- Kalembo F.W., Zgambo M., Mulaga A.N., Yukai D. and Ahmed N.I. Association between male partner involvement and the uptake of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) in Mwanza District, Malawi: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE; 8(6): e66517. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.e66517.(201 3).

- Farquhar C., Kiarie J.N., Richardson B.A., Kabura M.N., John F.N., Nduati R.W., Mbori-Ngacha D.A. and John-Stuart G.C. Antenatal couple counselling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmssion. J AcquirImmeDeficSyndr; 37(5): 1620-1626.( 2004).

- Byamugisha R., Tumwine J., Semiyaga N., And Tylleskar T. Determinants of male involvement the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programme in Eastern Uganda: a cross-sectional survey.Reproductive-health Journal. (2010).

- Adera A., Wudu W., Yimam Y., Kidane M., Woreta A. and Molla T. Assessment of male’s involvement in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and associated factors among males in PMTCT services. American Journal of Health Research; 3(4): 221-231. doi.10.11648/j.ajhr.2015.0304.14.(2015).

- Pontes C.M., Osório M.M. and Alexandrino A.C. Building a place for the father as an ally for breastfeeding. Midwifery; 25: 195-202. doi:10.1016/j.mdw.2006.09.004.(2006).

- Kalembo F.W., Yukai D., Zgambo M. and Jun Q. Male partner involvement in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: Successes, challenges and the way forward. Open Journal of Preventive Medicine; 2(1):35-42. doi:10.4236.ojpm .2012.21006.(2012).

- Aarnio P., Olsson P., Chimbiri A. and Kulmala T. Male involvement in antenatal HIV counselling and testing: exploring men’s perceptions in rural Malawi. AIDS Care, Francis and Tylor (Routledge); 21 (12): 1537-1546. doi.10.1080/09540120902903719.(2010).

- Skinner D., Mfecane S.,Gumende T., Henda N. and Davids A. Barriers to accessing PMTCT services in rural area of South Africa. AJAR; 4(2):115-123.(2005).

- Peacock D., Stemple L., Sawires S. and Coats T.J. “Men make difference”. Campaign launched in 2000 by the united nation to engage men in HIV prevention. Men, HIV and human rights. Journal Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndromes, 3, 119-125. doi:1097/QAI.obo 13e3181aafd8a.(2009).

- Bwambale F.M., Ssali S.N., Byaruhanga S., Kalyango J.N. and Karamagi C.A.S. voluntary HIV counselling and testing among men in rural western Uganda. BMC Public Health; 8: 263. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-263.(2008).

- Wade J.C. Traditional masculinity and African American men’s health related attitudes and behaviours. American Journal of Men’s Health; 3(2): 165-172. doi:10.117557988308320180.( 2009).

- Evans J., Frank B., Oliffe J.L. and Gregory D. Health, Illness, Men and Masculinity (HIMM): a theoretical framework for understanding men and their health. JMH; 8(1):7-15.(2011).

- Courtenay W.H. Engendering health: a social constructionist examination of men’s health believes and behaviours. Psychology of men and masculinity; 1(1): 4-15.(2000).

- Bourdieu P. Outline of a theory of practice. 3rd ed. USA. Cambridge University Press. (1987).

- Bourdieu P. Masculine domination. USA. Stanford University Press. (1989).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Projeções anunais da população total, urbana e rural dos distritos da província de Maputo 2007-2040. Maputo: Instituto Nacional de Estatística.(2010).

- Instituto Nacional de Saúde (INS), Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) e ICFInternational. Inquérito de indicadores de imunização, malária e HIV/SIDA em Moçambique (IMASIDA), 2015. Maputo: MISAU and INE.(2017).

- Feliciano, J. F. Antropologia económica dos Thongas do Sul de Moçambique. Maputo: Arquivo Histórico de Moçambique.(1998).

- Letuka P., Massashela M., Matashane-Marite K., Morolong B.L. and Motebang M.S. Family belonging form in Lesotho. Morija-Lesotho: Women and Law in Southern Africa Research Trust.(1998).

- Andrade X., Loforte A.M., Osório C., Ribeiro L. and Temba E. Families in a changing environment in Mozambique. Maputo: Women and Law in Southern Africa Research Trust.(1997).

- Franz N.K. The unfocused focus group discussion: benefits or ban? Education publication paper 9. Available at:http://lib.dr.ia state.edu_pubs/9(2011).

- Theuring S., Mbezi P., Luvanda H., Jordan-Harder B., Kunz A. and Harms G. Male involvement in PMTCT services in Mbeya region, Tanzania. AIDS Behav; 13: S92-S102. doi:10.1007/s10461-009-9543-0.(2009).

- Tilahun M. and Mohamed S. Male partners’ involvement in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and associated factors in Arba Minch Town and Arba Minch ZuriaWoreda, Southern Ethiopia. BioMed Research International. doi:10.1155/2015/763 876.(2015).

- Gebru A.A., Kassaw M.W., Ayene Y.Y., Semene Z.M., Assefa M.K., Hailu A.W. Factors that affect male partner involvement in PMTCT services in Africa: a review literature. Science Journal of Public Health; 3(4):460-467.(2015).

- Dunlap J., Foderinghan N., Bussell S., Western C.W., Audet C.M. and Aliyu M.H. Male involvement for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a briefs reviews of initiatives in East, West and central Africa. Curr HIV Rep; 11(2):109-118. doi.10.1007/s11940-014-0200-5.(2014).

- Morfaw F., Mbuagbaw L., Thabane L., Rodrigues C., Wunderlich A., Nana P. and Kunda J. Male involvement in prevention of programs of mother to child transmission of HIV: a systematic review to identify barriers and facilitators. Biomedical Central Systematic Reviews; 2(5). doi.10.11862046-4053-2-5.(2013).

- Belato D.T., Mekiso A.B. and Begashaw B. Male partner involvement in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services in southern central Ethiopia: in case of Lemo district, Hadiya Zone. AIDS Research and Treatment. doi:10.1155/2017/8617540.(2017).

- Yaya I., Landoh D.E., Saka B., Patchali P.M., Wasswa P., Aboubakari A., N’Dri M.K., Patassi A.A., Komaté K. and Pitche P.Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV and AIDS at the regional hospital of Sokondé, Togo. BMC Public Health; 14:1308. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1308.(2014).

- Adelekan A., Omoregie P. and Edoni E. Male involvement in family planning: challenges and way forward. International Journal of Population Research. doi:10.1155/2014/416457.(2014).

- Kabagenyi A., Jennings L., Reid A., Nalwadda G., Ntozi G. and Atuyambe L. Barriers to male involvement in contraceptive uptake and reproductive health services: a qualitative study of men and women’s perceptions in two rural Uganda. Reproductive health; 11:21. doi.1186/1742-4755-11-21.(2015).

- Emmanuel W., Edward N., Moses P., William R., Geoffrey O., Monicah B. and Rosemary M. Condom use determinants and practices among people living with HIV in Kisii county, Kenya. The open AIDS Journal; 9: 104-111.(2015).