Information

Journal Policies

Alcohol Consumption and Ischemic Heart Disease Mortality Trends in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine

Y. E. Razvodovsky

Copyright : © 2017 . This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: The Slavic countries of the former Soviet Union (fSU) Russia, Belarus and Ukraine retain one of the highest ischemic heart disease (IHD) mortality rates in the world, despite a gradual decline over the past decade.

Aims: The present study aims to analyze whether population drinking is able to explain the dramatic fluctuations in IHD mortality rates in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine from the late Soviet to post-Soviet period. Method: Trends in sex-specific IHD mortality rates and alcohol sales per capita from 1980 to 2010 in Russia Belarus and Ukraine were analyzed employing a Spearman’s rank-order correlation analysis.

Results: The estimates based on the Soviet data suggest a strong association between alcohol sales and IHD mortality rates in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. At the same time, the relationship between alcohol sales and IHD mortality was somewhat less evident in the post-Soviet period.

Conclusion: The findings from present study suggest that the IHD mortality fluctuations in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine in the Soviet period were attributable to alcohol. Alternatively, alcohol can not fully explain the fluctuations in the IHD mortality rates observed in these countries in the Soviet period.

alcohol sales, IHD mortality rates, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, 1980-2010.

1. Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Europe [1]. Recorded IHD death rates vary widely across European countries [2]. The Slavic countries of the former Soviet Union (fSU) Russia, Belarus and Ukraine retain one of the highest IHD rates [3,4]. Understanding the huge regional variations in IHD mortality is crucial to the development of effective prevention strategies. A number of risk factors have been linked to the east-west gradient in IHD mortality including socio-economic (low income), psychosocial (stress) and lifestyle (diet, smoking, hazardous drinking, low physical activity) variables [5,6]. A great deal of evidence indicates that alcohol has been implicated both in the high IHD mortality and its dramatic fluctuation during the recent decades in the fSU republics [7-12] but the magnitude of this effect remains unclear.

The present study aims to analyze whether population drinking is able to explain the dramatic fluctuations in IHD mortality rates in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine from the late Soviet to post-Soviet period. More specifically, this study focuses on a comparative analysis of sex-specific IHD mortality rates and alcohol sales per capita in these countries between 1980 and 2010.

2. Methods

The data on gender-specific IHD mortality rates (per 100.000 of the population) were taken from the WHO mortality database. The data on per capita alcohol sales (in liters of pure alcohol) are taken from the National Statistical Committees. The data were broken into two periods (from 1980 to 1991 and from 1992 to 2010) to determine whether the link between alcohol sales and IHD mortality rates has altered in the post-Soviet period. To examine the relation between changes in alcohol sales and IHD mortality rates across the study period a Spearman’s rank-order correlation analysis was performed using the statistical package "Statistica".

3.Results

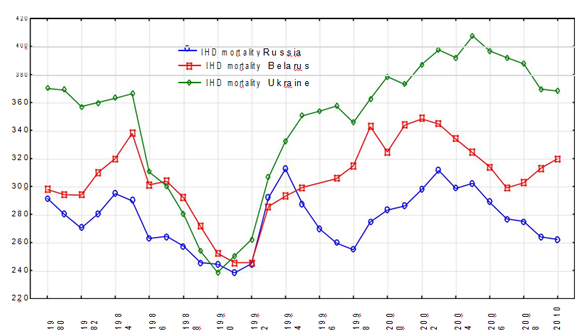

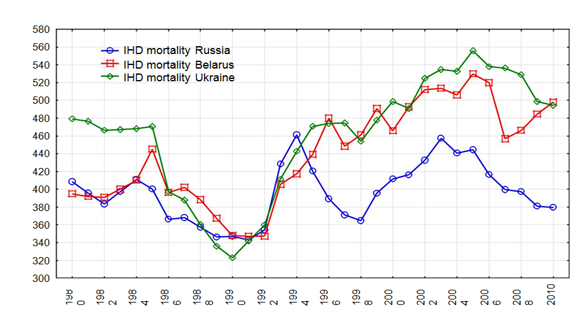

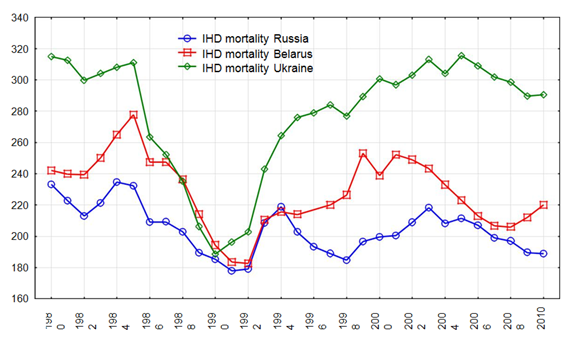

The average male IHD mortality rates figure for Russia, Belarus and Ukraine was 396.3±32.5, 439.2±55.3 and 460.3±65.2, while the average female IHD mortality rates was 204.5±15.4, 228.6±22.9 and 278,3±37.7 per 100.000 respectively. Since the early 1980s, IHD mortality rates in these countries have undergone sharp fluctuations (Figure. 1).

As can be seen, three countries have experienced similar fluctuations in the IHD mortality rates over the Soviet period. This index decreased markedly in the yearly 1980-x, than dropped sharply between 1985 and 1991. While the trends in IHD mortality rates have been similar in three countries during the Soviet period, there was market discrepancy after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In Russia IHD mortality rates jumped dramatically between 1991 and 1994,declined between 1994 and 1998, increased again until 2003, and than began to decline. In Belarus IHD mortality rates increased steadily up to 2002, decreased substantially between 2002 and 2007 and than started an upward trend. In Ukraine, IHD mortality increased dramatically between 1991 and 1995 reaching its pick in 2005 and than started to decrease.

The comparative analysis of long-term evolution of IHD mortality rates suggest that in the yearly 1980s the rates was considerably lower in Belarus and Russia than in Ukraine, but this gap practically disappeared in the yearly 1990s, when IHD mortality in three countries reached its lowest point for the entire period. It is important to point out that the temporal pattern of IHD mortality for men and women was uniform, but it appears that the male rate tends to fluctuated across time series to a much greater extent than the female rate (Figure. 2-3).

It should be also emphasize that Ukraine men and women have experienced the sharpest decrease in IHD mortality rates in the second half of 1980s.

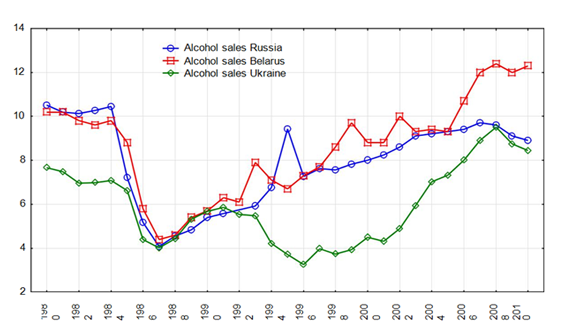

The average per capita alcohol sales figure for Russia, Belarus and Ukraine was 8.0±1.9, 8.6±2.2 and 5.9±1.8 litres per capita respectively. The temporal pattern of alcohol sales per capita in all countries was similar across the Soviet period (Figure. 4).

As can be seen, the alcohol sales decreased slightly in the early 1980s, and than decreased dramatically between 1984 and 1987. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, recorded alcohol consumption in Russia rose sharply between 1992 and 1995, decreased substantially in 1996, increased steadily up to 2007, and than started to decrease. In the post-Soviet Belarus alcohol sales increased steadily with several oscillations up to 2005, than jumped dramatically, and since 2011 started to decrease. In the post-Soviet Ukraine alcohol sales decreased markedly between 1991 and 1996, increased dramatically between 1996 and 2008, and than started to decline.

The graphical evidence suggests that in the Soviet period, the gender-specific temporal pattern of IHD mortality rates fits closely with changes in alcohol sales per capita in all countries (Figure. 1-4). By contrast, there was significant discrepancy between these trends in the post-Soviet period. The outcomes of the Spearman’s correlation analysis are presented in Table 1.

The estimates based on the Soviet data suggest a strong association between alcohol sales and IHD mortality rates in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine for both sexes. At the same time, the relationship between alcohol sales and IHD mortality rates in the post-Soviet period was positive, but statistically nonsignificant for men and women in Russia, positive for men in Belarus, positive for both sexes in Ukraine.

4. Discussion

This study provides empirical evidence that in the fSU republics there have been parallel fluctuations in recorded alcohol consumption and IHD deaths during the Soviet period. It is obvious that the sudden decline in IHD mortality seen in the mid-1980s was a consequence of Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign, which substantially reduced recorded alcohol consumption [13]. So, Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign offer direct evidence that reduced population drinking did bring decrease IHD mortality. Increase in population drinking, fuelled by the availability of alcohol was also implicated in the dramatic growth in IHD mortality that followed by the collapse of the SU in the yearly 1990s [14].

According to the results of present analysis there was a positive and statistically significant effect of per capita alcohol sales on gender-specific IHD mortality rates in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine in the Soviet period. The magnitude of this effect was similar for male and female in all countries. In the post-Soviet period the effect of alcohol sales on IHD mortality rates was somewhat less evident. In general, these results replicate previous findings that suggested a close link between alcohol and IHD mortality at the aggregate level [15].

Since 2003, Russia has experienced steep decline in IHD mortality rates. What is unclear, however, is whether this trend is simply the latest phase in a continuing cycle of fluctuations that have characterized IHD mortality in Russia over the past three decades, or whether there are new features that mark a break from the past. Several experts hypothesized that the reduction in the number of IHD mortality deaths during the last decade might be attributed to the implementation of the alcohol policy reforms in 2006, which increased government control over the alcohol market [16-19]. There is, however, some doubts that recent decline in IHD mortality rates in Russia is fully attributable to the alcohol control measures, since downward trend in IHD mortality rates started before the implementation of the alcohol policy reforms. It might be especially true, since specific alcohol control measures were not implemented in Belarus and Ukraine during recent decade. An alternative explanation might be that the decline in Russian IHD mortality rates is simply following a regional pattern that happened to coincide with the implementation of alcohol control measures. The downward trend in the IHD mortality rates in the fSU countries over the past decade might be attributed to the macro economic stabilization.

Before concluding, we should address the potential limitations of this study. In particular, we relied on official alcohol sales data as a proxy measure for trends in alcohol consumption across the period. However, statistics on recorded alcohol consumption suffer from a high degree of uncertainty, especially in the post-Soviet period [20]. The three countries largely share the same experiences with statistics before the collapse of the Soviet Union [21]. The central statistical agencies of newly independent republics continued the traditional Soviet method of alcohol sales data collections. At the same time, the abolishment of the state alcohol monopoly and the appearance of private retail trade outlets during the period of transition made such data collection more difficult and the resulting alcohol statistics less reliable [14]. Unrecorded consumption of alcohol was commonplace in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine throughout the study period, especially in the mid-1990s, when a considerable proportion of vodka came from illicit sources [20]. In comparative perspective, Ukraine has the largest share of unrecorded alcohol in total alcohol consumption [22]. It has been estimated that unrecorded alcohol makes up two-third of overall alcohol consumption in this country [23]. The amount of recorded consumption as a proportion of total consumption in Ukraine has decreased dramatically during the period of transition. According to estimates by the Ukrainian Alcohol and Drug Information Centre recorded alcohol consumption ranged between 6.3 litres in 1980 and 2.0 in 1994, while corresponding figures for unrecorded consumption of alcohol were 5.0 and 9.5 litres per capita [23]. An uncertainty about the actual alcohol consumption figures is likely to have distorted the time series association between population drinking and IHD mortality rates in the post-Soviet period. Further, doubts have been raised about the validity of cross-national comparisons in IHD mortality because enormous variations across countries in coding prictice with respect to the ill-defined cardiovascular codes [2]. The misclassification of sudden cardiac deaths often associated with binge drinking in Russia may also conceal true causes of IHD [24].

In conclusion, the findings from present study suggest that the IHD mortality fluctuations in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine in the Soviet period were attributable to alcohol. Alternatively, alcohol can not fully explain the fluctuations in the IHD mortality observed in these countries in the Soviet period. Similar regional pattern of IHD mortality trends do not support the hypothesis that alcohol control policy was responsible for the decline in Russian IHD mortality rates during recent decade. Further monitoring of IHD mortality trends in the former Soviet countries and detailed comparisons with earlier developments in other countries remain a priority for future research.

References

- Rayner M, Allender S, Scarborough P. (2009). Cardiovascular disease in Europe. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation 16(Suppl. 2):43-S47.

- Kim AS, Johnston SC (2011). Global variation in the relative burden of stroke and ischemic heart disease. Circulation 124: 314-323.

- Ginter E. (1995). Cardiovascular risk factors in the former communist countries. Analysis of 40 European MONICA populations. European Journal of Epidemiology, 11, 199-205.

- Moskalewicz JR, Razvodovsky YE, Wieczorek L. (2016). East-west disparities in alcohol-related harm. Alcoholism and Drug Addiction, 29: 209– 222.

- Petruchin IS, Lunina EY(2012). Cardiovascular disease risk factors and mortality in Russia: challenges and barriers. Public Health Review 2: 436-449

- Sidorenkov O, Nilssen O, Grjibovski AM (2012) Determinants of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in northwest Russia: a 10-year follow-up study. Ann Epidemiol 22:57-65.

- McKee M, Shkolnikov V & Leon DA. (2001). Alcohol is implicated in the fluctuations in cardiovascular disease in Russia since the 1980s. Annals of Epidemiology, 1, 11-6.

- Razvodovsky Y E. (2001). Alcohol and cardiovascular mortality: epidemiological aspect. Alcologia, 13(2), 107-113.

- Razvodovsky YE. (2009). Aggregate level beverage specific effect of a sale on myocardial infarction mortality rate. Adicciones, 21(3), 229-238.

- Razvodovsky YE. (2009). Alcohol poisoning and cardiovascular mortality in Russia 1956–2005. Alcoholism, 45(1), 27-42.

- Razvodovsky YE. (2010). Beverage-specific alcohol sale and cardiovascular mortality in Russia. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, Article ID:253853.

- Razvodovsky YE (2013). Alcohol-attributable fraction of ischemic heart disease mortality in Russia. ISRN Cardiol: 287869.

- Razvodovsky YE (2016). The effect of Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign on cardiovascular mortality in Belarus. Journal of Heart Health. 2(4):1-3.

- Nemtsov AV, Razvodovsky YE (2008). Alcohol situation in Russia, 1980-2005. Social and Clinical Psychiatry 2: 52-60.

- Hemstrom O. (2001). Per capita alcohol consumption and ischemic heart disease mortality. Addiction, 96:93-112.

- Schkolnicov VM, Andreev EM, McKee M, Leon DA. (2013). Components and possible determinants of the decrease in Russian mortality in 2004–2010. Demographic Research 28:917–950.

- Razvodovsky YE. (2014). Was the mortality decline in Russia attributable to alcohol control policy? Journal of Sociolomics 3:2.

- Nemtsov AV, Razvodovsky YE. (2016) Russian alcohol policy in false mirror. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 4: 21.

- Razvodovsky YE, Nemtsov AV. (2016). Alcohol-related component of the mortality decline in Russia after 2003. The Questions of Narcology. 3.63-70.

- Razvodovsky YE. (2008). Noncommercial alcohol in central and eastern Europe, ICAP Review3. In: International Center for Alcohol Policies, ed. Noncommercial alcohol in three regions. Washington, DC: ICAP:17–23.

- Treml VG. (1975) Production and consumption of alcoholic beverages in the USSR. A statistical study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 36, 285–320.

- Levchuk N. (2005) “Demographic Consequences of Alcohol Abuse in Ukraine”, Demography and Social Economy, 8: 46-56,

- ADIC-Ukraine (1995). Alcohol ta narkotyky v Ukraini [Alcohol and Drugs in Ukraine]. Alcohol and Drug Information Center (ADIC). Kyiv, 96 p.

- Gavrilova NS, Semyonova VG, Dubrovina E, Evdokushkina GN, Ivanova AE, Gavrilov LA. (2008). Russian Mortality Crisis and the Quality of Vital Statistics. Population Research and Policy Review. 27(5): 551–574.