Information

Journal Policies

Palliative Care - An Indian Perspective

Ira Khanna, Ashima Lal

Copyright : © 2016 Ira K. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Palliative care in India is a relatively new concept; developed over the past 30 years, compared to 50 years in the developed nations. The Government of India initiated a National Cancer Control Programme to make pain relief one of the basic services to be provided at the primary health care level. Kerala is often cited as a ‘beacon of hope’- contributing to two-thirds of India’s Palliative care services, being the home of only 3% of India’s population of 1.2 billion. Since 2008, there has been a formal palliative care policy in place within the Kerala state government providing funding for community based programs. It was also one of the first states in India to make the narcotics regulations more flexible to permit use of morphine by Palliative Care providers. The Palliative Care Center in Calicut, Kerala, has become a WHO demonstration project serving as an example of low cost and high quality Palliative Care delivery in the developing world based on cooperation between government, non-government organisations and the community.

Despite the efforts of non government organisations such as Pallium India in helping the government to create the National Program in Palliative Care in 2013 as well as spearheading the 2014 amendment in the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, the reach of Palliative Care across the country remains limited. As health care providers, we need to work together to ensure more patients are receiving the interdisciplinary, holistic approach they deserve.

1.Palliative Medicine - A Necessity In Patient Care

A 58 year old lady, Ms. I with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease would arrive at the emergency department at a leading government hospital in New Delhi, India every other week presenting with severe dyspnea. She would be nebulised, admitted to the the medical floor followed by an intensive care unit stay with impending respiratory failure, discharged after treatment, only to return a few weeks later. The physicians worked very hard on this patient every time she was admitted, however, unfortunately she suffered immensely, ultimately dying in the ICU rather than at home.

In contrast, at Grady Memorial, Atlanta, a 60 year old man (Mr. U) with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presented to the emergency with severe dyspnea. He was nebulised, admitted to the medical floor, prescribed morphine, had a fan directed to his face, had his goals of care discussed and signed, and had home oxygen arranged by his home hospice agency upon discharge. Incorporation of Palliative Medicine in patient care across all fields of medicine is known to alleviate patient distress as well as improve quality of life. Although Palliative Medicine is a field of expertise, primary palliative care is a skill that all physicians world -wide should have.

2. Palliative Care

The World Health Organization defines Palliative Care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual”[1].

Palliative care involves a multidisciplinary team including the patient, family, Palliative Medicine and Primary Care physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, clergy, counselors, speech, physical and occupational therapists, dieticians and volunteers. In the United States, Palliative Care is provided as an inpatient and outpatient service. As an inpatient service, there are a few models - consultative, integrative or a mixed model. In the consultative model, the patients have access to Palliative Care physicians on a consultation basis; whereas, the integrative model involves primary team physicians trained with palliative skills. The mixed model entails both consultative and integrative models in which physicians with primary palliative skills have access to specialists as consultants. While symptom management is often provided to hospitalized patients, it should also be a focus in outpatient clinics. Perhaps allocating more resources for outpatient palliative care can decrease hospital admissions and improve quality of life.

When learning of these different models, I thought back on Ms. I and Mr. U and understood why their clinical scenarios varied so much. If Ms. I and her family had the benefit of discussing with a palliative team, or at least with a physician with basic palliative skills, her outcome could have been different. Perhaps one reason why she was not referred to a home care, regardless of if hospice was involved, is because COPD has a variable trajectory of illness. Prognostication can at times be difficult however strongly influences medical decision making.

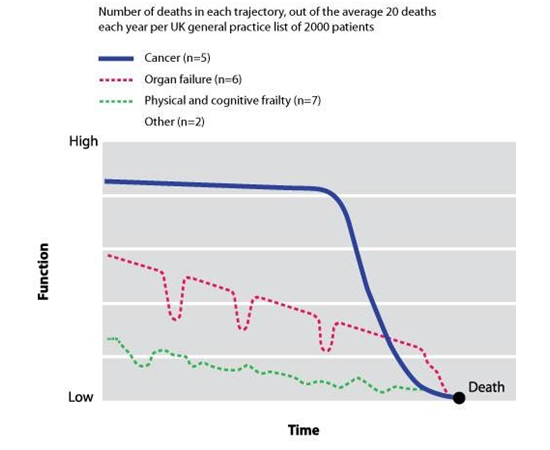

Palliative Care is beneficial at any stage of illness, often offered concomitantly with curative treatments. Figure 1 shows the different trajectories of illness at the end-of-life. Physicians must be aware of and discuss illness trajectories with patients and families so as to allow the option of supportive care, focusing on quality of life and symptom control to be offered to the patient earlier in disease course even alongside ongoing curative management. Ms. I and Mr. U followed the organ failure trajectory with prominent dips signifying acute exacerbations, where there is a significant risk of mortality with each episode. Nevertheless, COPD patients are known to experience better quality of life if they are provided Palliative Medicine services.

3. Palliative Care and Hospice

Hospice care is palliative in nature, however it is provided for an illness that is certified as terminal (life expectancy < 6 months) by two physicians (covered by Medicare in the US) [3]. In India, it seems there is no definitive eligibility criteria described for admission to hospice. Hospice care is typically provided as an outpatient home care with family members as the primary caregivers, however, it may also be provided in nursing homes or hospital inpatient units. The goal is to provide comfort and quality of life as well as to avoid aggressive, futile care at the end of life [4]. Dignity in death is something each and every one of us hopes for when our time comes. How many of us actually achieve that goal, is a question we would not like the answer to. Hospice provides the benefit and dignity in allowing death to occur at home, thus providing a familiar, comfortable environment for patients suffering from terminal illnesses.

Hospice focuses not only on the patients but on the caregivers and family members as well, which forms the basis for the concept of respite. Respite programs provide short-term breaks for caregivers with the goal of preventing caregiver burnout. This is aimed to provide support to families to deal with the physical and emotional consequences of caring for their loved one. There is a study currently underway at the Cancer Center of Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, evaluating the effectiveness and applicability of Respite model of Palliative Care (Salins et al)[5]. The cancer center has partnered with a charitable trust to form a Respite Care facility, acting as a bridge between hospital and home based Palliative Care, thereby empowering the caregivers and ensuring continuity of care for the patient. Table 1 compares palliative care and hospice care.

4.Global Timeline of Palliative Care Development

During the 12th-20th centuries, the word „hospice‟ referred to a place of rest for travellers or pilgrims. The modern „hospice movement‟ began in 1967 with the establishment of St. Christopher‟s Hospice in the UK by Dr. Cicely Saunders. Interestingly, she was originally a medical social worker, then trained as a Registered Nurse and finally advanced her career to become a physician. Being involved in the care of terminally ill patients, she lectured widely, wrote various articles on this subject and was a pioneer in the field of Palliative Medicine. The St. Christopher‟s Hospice, when opened for service, had inpatient facilities for 54 patients with a 16 bed residential wing for elderly patients and a planned bereavement service. Home care started two years later [6].

The concept of Palliative Care was established in North America when Dr. Balfour Mount founded the Palliative Care Service in the Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal [7]. Inspired by Dr. Cicely Saunders, the first Hospice in the US was founded in 1974, the Connecticut Hospice in Branford, Connecticut, by Florence Wald, Dean of Yale School of Nursing along with two pediatricians and a chaplain [8]. In 1987, the quarterly „Hospice Bulletin‟ was released which quickly came into international circulation [9]. With further spread of palliative care worldwide, it was observed that „All world cultures have traditional strengths that can contribute to the success of a palliative care programme‟ [10]. In 2006, Hospice and Palliative Medicine was recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties. However, as of 2010 there is an acute shortage of Hospice and Palliative Care physicians in the US, the gap estimated to be around 6000-18,000 physicians [11].

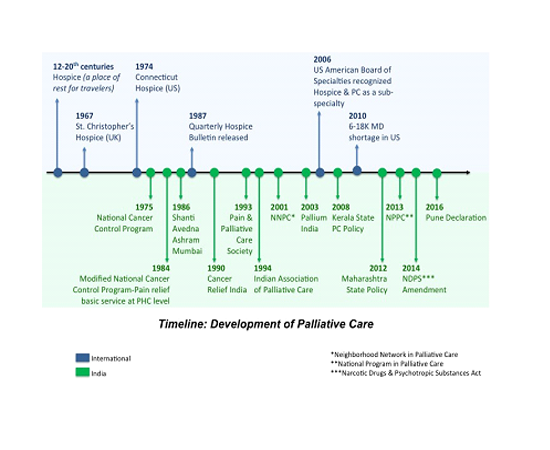

Palliative care in India is a relatively new concept having developed only over the past 30 years, compared to 50 years in the developed nations. The Government of India initiated a National Cancer Control Programme in 1975 [12], modified in 1984, to make pain relief one of the basic services to be provided at the primary health care level. This policy however, was not translated into large-scale service provision [13]. The first Hospice facility in India, based on the traditional western model of an inpatient hospice, the Shanti Avedna Ashram, was opened in Mumbai in 1986. Cancer Relief India, a UK charity, founded in 1990, aimed at educating doctors and nurses in Palliative Care and to provide pain and symptom relief for cancer patients [14]. The Pain and Palliative Care Society (PPCS) was formed in 1993 in Calicut, Kerala and functioned purely on the basis of volunteerism. It eventually developed an outpatient service and a home visit programme with the help of World Health Organisation (WHO). The WHO also helped form the Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) in 1994 with predominantly anaesthetists from all over India as the initial founding members, as they were the ones most commonly involved in pain management [15]. Figure 2 shows the timeline of Palliative Care development in the world and in India.

5.Palliative Care In India - Current Scenario

Currently, there are over 908 Palliative Care centers in India, which are accessible to a mere 1% of a population of over 1.2 billion people. India is a nation which has the worst of both worlds- communicable diseases and infections are still rampant and there has been an exponential rise in the prevalence of chronic lifestyle diseases and cancer. It is estimated that 5.4 million people a year are in need of Palliative Care in India [16]. However, these services, apart from being inadequate for such a large population, are mostly concentrated in large cities and regional Cancer Centers.

Palliative Care services in Kerala, however, are more far-reaching with 841 centers out of the 908 located in this state [17]. Kerala is unusual, having the highest literacy rates and health indices in the country which also contributed to an active political leadership. Services in these centers include inpatient provision, outpatient clinics and home care services- which make use of the strong family structure in India, where relatives want to take care of the chronically ill. Even though Kerala serves as a WHO model for Palliative Care services for the developing world, the rest of the country is lagging behind due to lower literacy rates, unawareness of the concept of Palliative Care and varied cultural attitudes to chronic illness and death across different communities.

India ranks at the bottom of the Quality of Death Index [18]. The Quality of Death Index, commissioned by the Lien Foundation, Singapore, measures the quality of Palliative Care in 80 countries around the world, using 20 quantitative and qualitative indicators across five categories: the Palliative and Healthcare environment, human resources, the affordability of care, the quality of care and the level of community engagement. While the UK and the US rank 1st and 9th respectively; India ranks 67th. Kerala is often cited as a „beacon of hope‟, contributing to two-thirds of India‟s Palliative care services, being the home of only 3% of India‟s population. Since 2008, there has been a formal palliative care policy in place within the Kerala state government providing funding for community based programs [19]. It was also one of the first states in India to make the narcotics regulations more flexible to permit use of morphine by Palliative Care providers. The Palliative Care Center in Calicut, Kerala, has an inpatient unit, an outpatient care center with satellite clinics in surrounding towns as well as home care services with the involvement of lay volunteers and family members. The Calicut model has become a WHO demonstration project serving as an example of low cost and high quality Palliative Care delivery in the developing world based on cooperation between government, non- government organisations and the community [20]. Maharashtra has also announced a state Palliative Care policy in 2012 which, however, has not yet come to fruition [21].

6.Neighbourhood Network In Palliative Care, Keralao

The Neighbourhood Network in Palliative Care (NNPC), Kerala, was developed in 2001. Social activism has always been an integral part of Kerala‟s heritage. This tradition of social activism fueled the setting up of community-owned units in rural areas with the support of medical and nursing teams from The Pain and Palliative Care Society (PPCS), funded mostly by the local community [19]. The program trains volunteers from the local community to identify the symptoms and psychosocial issues of chronically ill members of their areas and to intervene effectively with the help of a network of trained professionals. Covering a population of over 12 million, the NNPC is probably the largest community-owned Palliative Care network in the world [22]. It is based on the theory of Primary Health Care, defined by the World Health Organisation as “essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self- reliance and self-determination.”

The NNPC now operates in all 14 districts of Kerala through a network of 230 clinics/units comprising of 60 full-time physicians, 150 staff nurses, 200 auxiliary nurses and over 10,000 trained volunteers. Each unit has around 400 patients under their care at any given time, with the network as a whole seeing over 2500 patients per week [19]. The NNPC program identifies interested volunteers from within the community willing to spend at least 2 hours every week helping patients in their area. The training program includes 16 hours of interactive theory sessions along with a minimum of four “clinical days” with the home care teams. The volunteers are educated about the philosophy of Palliative Care, the role of community, basics of cancer and HIV/AIDS, assessment of patients as a whole, basic nursing care, home care as well as issues related to terminal care [23]. This program is similar to the American Home Hospice system, wherein, a nurse makes home visits. Table 2 indicates the sources of funds for NNPC in 2008-2009 (Kumar et al) [23].

7.Cultural Considerations

India is a culturally diverse nation where death is often a taboo subject. Many consider talking about death as disrespectful or ill luck. Some may actively “protect” dying family members from knowing their prognosis. There is a culture of collective decision-making, where family members, mostly the male head of the family, takes over the end-of-life care decision making role for seriously ill patients. There is immense faith in traditional healing methods including herbal and folk remedies. Practices of death and dying in India differ vastly owing to the plethora of cultural and religious traditions- with cremation being the practice among Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists; while in Islam the practice is burial. Hindus believe in reincarnation, wherein the eternal soul passes from one existence to the next. Buddhists believe in rebirth described as the continuation of the existence of the dependent soul. Various cultural practices include chanting or singing hymns to help their loved one transition, with most of the focus being on the afterlife. However, not enough emphasis is placed on the dying process.

Although the availability of family support and the concept of allowing death to occur in the comfort of a patient‟s home fits nicely with the Indian culture‟s values and beliefs; there is not enough awareness of Palliative Care services in the majority of the country. Benefits of Palliative care include improved symptom management, increased patient and family satisfaction, increased savings of the healthcare system by decreased use of aggressive, non-beneficial treatments at end of life.

8.Palliative Care Policy Development In India

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, in consultation with Pallium (a charitable trust for Palliative Care in India founded in 2003), developed a National Palliative Care Strategy, which eventually formed the National Program of Palliative Care for India (NPPC), 2012-2017. The objectives of the National Palliative Care Strategy are listed in Table 3. However, due to lack of budget allocation, with only 2% of the proposed budget (460.38 million Indian Rupees) being released, a very small part of the programme was implemented in a minority of states [15]. Along with lack of budget allocation, perhaps other barriers to Palliative Care could be provider based – fear of being unethical, litigation, negative psychosocial impact, inability to prognosticate or developing an emotional attachment to patients; or patient/family based – psychological attachment, inability to recognize that death is near, inability to accept limitations of further aggressive medical care, hope for miracles or fear of religious or ethical impropriety. Thus, without increasing provider awareness and education, patients will unlikely be able to benefit from a dignified death.

Pallium India created an implementation framework in 2013 for NPPC, spelling out strategies and timelines which was submitted to WHO India and Ministry of Health. Its operational analysis by the WHO India office did not materialize yet. Pallium India also undertook the initiative for developing curricula for undergraduate medical and nursing education, with a scheme of incorporating Palliative care education into the current curricula. Action on this is yet to be taken by the Medical Council of India and the Indian Nursing Council [15]. In terms of medical education, there are two postgraduate training positions for MD in Palliative Medicine per year and only a handful of certificate programs and fellowships ranging from 4 weeks to 1 year [17].

A major victory for Palliative Care in India came in 2014 with the amendment of the immensely restrictive and stringent Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (NDPS), 1985. Access to opioids has been a major barrier to Palliative Care services in India, which was complicated further by the fact that control of opioid medicines was a “state subject” in India‟s federal system of governance. In 1998, a pharmacologist, Ravindra Ghooi approached the Delhi High Court seeking access to morphine for his mother with debilitating cancer pain. The High Court in this case passed an order asking the Delhi Government to take prompt action. Following this, the Government of India prepared a model rule for modification of existing state regulations for all states to adopt. However, most states did not bring about the changes suggested [15].

A Human Rights Council report states that “In 2008, India used an amount of morphine that was sufficient to adequately treat during that year only about 40,000 patients suffering from moderate to severe pain due to advanced cancer, about 4% of those requiring it.”[24] The NDPS Amendment Act, 2014, called for uniform, simplified NDPS rules across the country. It transferred the legislative powers on “essential narcotic drugs” from the state governments to the central government. This eliminated the need for securing licenses from multiple state departments before the drugs can be procured, stocked and dispensed for medical use by pharmacies or healthcare facilities. It is now up to the state governments and Palliative Care providers to ensure that the amended rules are implemented and to create awareness of the newly amended act amongst healthcare providers, pharmacists and the general public [25]. Of the many states within India, only a handful i.e. Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Delhi have shown improvement to access to opioids. Coincidentally, these states are those that had some baseline Palliative Care activity, which goes to show the pressing need for further education.

Despite all the recent developments, benefit from Palliative Care services reaches only about 1% of the 1.2 billion people of India. The 23rd International Conference of the Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPCON2016) held at Pune in February 2016, has issued a „Pune Declaration‟ urging the Government of India to give “the rightful place for palliative care in its Non-Communicable Diseases Control Programme and in its HIV and TB Control Programmes,” in accordance with the World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution of 2014. It requires its 194 member states “to integrate evidence-based, cost-effective and equitable Palliative Care services in the continuum of care, across all levels, with emphasis on primary care, community and home-based care and universal coverage schemes.” The Pune Declaration has appealed to the Indian Government for adequate funding for timely and effective implementation of the NPPC 2012, the NDPS Amendment Act 2014 as well as the inclusion of Palliative Care in undergraduate medical and nursing curricula. Dr. M.R. Rajagopal, Director of the Trivandrum Institute of Palliative Sciences (a WHO Collaborating Centre), Founder Chairman of Pallium India and a pioneer in Palliative Care development in India, called for clear guidelines for government collaboration with Non-Government Organisations “to act as technical advisory agencies for the process of community awareness, mobilisation and empowerment in the field of palliative care programmes.”[26] Without implementation of these practices, a great deal of the population will fail to benefit.

9.Palliative Care Concept In India- Advantages And Disadvantages

Compared to developed countries, India has many advantages and disadvantages when it comes to the implementation of Palliative Care and Hospice (Table 4).

10.Conclusion

Palliative Care seems to be a luxury in India. While key members are making pushes on the government, education in the field of Palliative Medicine is lacking in India when compared to the developed world such as Australia, Europe and the US. Although there have been recent developments in the curriculum for healthcare providers ranging from nurses to doctors, they have yet to be implemented. In other countries, there are defined guidelines for healthcare providers to refer to when discussing hospice eligibility. India does not seem to have this, yet. The question remains, how do we improve access to Hospice and Palliative Care in developing countries? Using a model that has been established in Kerala by enlisting the help of lay people in the community in addition to providing education to key providers is a good start. Had Ms. I been provided basic Palliative care, she may not have been in such terrible distress at the end of her life, she could have experienced a more comfortable and more peaceful death. It should not take a personal experience of a painful death of a loved one for providers and the general public to value the philosophy of aggressive Palliative Care in the end-of-life.

11.Acknowledgement

IK thanks the staff and patients at Grady Memorial Hospital and Emory University for providing an opportunity to observe their world-class palliative care system. IK thanks Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India for the excellent training in patient care.

References

- World Health Organization. National cancer control programmes: policies and managerial guidelines, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002.

- Murray SA et al. Illness trajectories and Palliative Care. Br Med J 2005; 330(7498):1007-1011.

- Rinaldo MJ. Medicare to cover hospice services. J Med Soc NJ 1982; 79:1015–1016.

- Davis MP, Gutgsell T, Gamier P. What is the difference between palliative care and hospice care?. Cleve Clin J Med 2015 Sep; 82(9):569-71.

- Salins N, Muckaden MA, Chowdhury J, Deodhar J. Respite model of Palliative Care for advanced cancer in India: Development and evaluation of effectiveness. J Palliat Care Med 2015; 5:5.

- Saunders C. The evolution of palliative care. J R Soc Med 2001 Sep;94(9):430-432.

- Williams MA, Wheeler MS. Palliative care: what is it?. Home Healthc Nurse 2001;19(9):550-6.

- Hospice: A historical perspective. Retrieved from http://www.nhpco.org/history-hospice-care.

- Saunders C. Hospice: a global network. J R Soc Med 2002 Sep; 95(9): 468.

- Saunders C, Kastenbaum R. Hospice on the International Scene. New York: Springer, 1997.

- Lupu D. Estimate of Current Hospice and Palliative Medicine Physician Workforce Shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40(6):899-911.

- Rajagopal MR, Kumar S. A model for delivery of palliative care in India-the Calicut experiment.J Palliat Care 1999;15:44-49.

- Rajagopal MR, Venkateswaran. Palliative care in India: successes and limitations. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2003;17:121-128.

- Webb PA. Cancer relief in India. Eur J Cancer Care 1993; 2:2.

- Rajagopal MR. The current status of Palliative Care in India. Cancer Control 2015;57-62.

- Kar SS, Subitha L, Iswarya S. Palliative Care in India: Situation assessment and future scope.Indian J Cancer 2015;52(1):99-101.

- Proposal of Strategies for Palliative care in India. (2012, Nov). Retrieved from: http://pallium india.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/National-Palliative-Care-Strategy-Nov2012 .pdf.

- The 2015 Quality of Death Index, Ranking palliative care across the world- A report by the The Economist Intelligence Unit. Retrieved from: http:// www.eiuperspectives.economist.com /sites/ default/files/images/2015%20EIU%20Quality%20of%20Death%20Index%20Oct%2029%20FI NAL.pdf.

- Sallnow L, Kumar S, Numpell M. Home-based palliative care in Kerala, India: the Neighbourhood Network in Palliative Care. Prog Palliat Care 2010; 18 (1):14-17.

- Seamark D et al. Palliative care in India. J R Soc Med 2000; 93:292-295.

- Maharashtra Palliative Care Policy (Draft), 2012. Available from: http:// palliative.micraft.org/ wp-content/uploads/2014/08/maharashtrapalliative-care-policy-2012.pdf.

- Kumar SK, Palmed D. Kerala, India: A regional community-based Palliative care model. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 33(5):623-627.

- Kumar S, Numpeli M. Neighborhood Network in Palliative Care. Indian J Palliat Care 2005; 11(1):6-9.

- Human Rights Council. Report of the special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak, A/HRC/10/44, para 72. 2009 Jan 14. Available from: http:// www2.ohchr.org /english/bodies/ hrcouncil/docs/ 10session/ A. HR C.1 0. 44AEV.pdf.

- Bandewar SV. Access to controlled medicines for palliative care in India: gains and challenges.Indian J Med Ethics 2015;1-6.

- Kulkarni P. Pune Declaration urges India to implement WHA resolution on integrated Palliative care, Feb 2016. Available from http://www.ehospice.com/Default/tabid/10686/ArticleId/18503.